The face and landscape of the Indian press got exposed after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi clamped a countrywide emergency rule close to midnight on June 25, 1975

This week 43 years ago, the realm of Indian newspapers from across Nepal’s border shocked and amused Nepalis. It also dawned on them how democratically elected leaders fall for dictatorship in the name of national security. After India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi clamped a countrywide emergency rule close to midnight on June 25, sending a shock wave across the world’s “largest democracy” and other democracies, the face and landscape of the Indian press got exposed. Arrests of opposition leaders began at midnight itself, literally torn away from their beds and family members.

That was after a court verdict on June 12, 1975 found her guilty of election malpractice in the 1971 elections, as the opposition pressed for her resignation. The socialist Jaya Prakash Narayan rallied the opposition for “total revolution”. Only six weeks earlier President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed had given his assent to Sikkim Bill after a hurriedly held referendum in Sikkim on April 4 gave an astonishing 97 percent margin to the protectorate’s merger with Indian Union. New Delhi had also militarily helped Pakistan’s Eastern wing to emerge as an independent Bangladesh toward the end of 1971.

People were, however, not prepared to hail a leader who was guilty of malpractice in the vital process of democratic elections. Hence, Gandhi went for emergency solely to keep herself in power. She asked a pathetically submissive president to sign the document declaring the emergency without any grave crisis or security threat to the nation.

During the emergency, the Indian press kowtowed to the government so much so that opposition leader Lal Krishna Advani later complained: “When they were asked to bend, they crawled.” The functioning of the Indian press gave a picture many Nepali readers imagined would never be possible.

Press Council Nepal draws Press Council of India's attention ov...

Authoritarian audacity

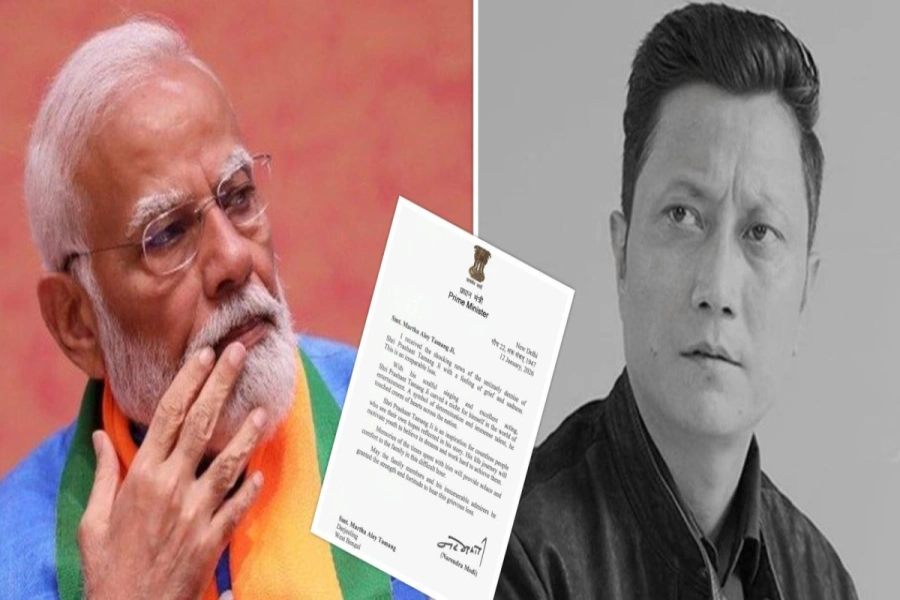

In the wake of its poor performance in the Karnataka state assembly polls last month, Indian National Congress President Rahul Gandhi accused Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party of creating fear in the people and sensitive institutions to the extent of exercising self-censorship in their speech and action. Typical of politicians who quote out of context to suit their expediency, he chose to forget how his grandmother Indira Gandhi had terrorized the people and news media for two and half years. He was five when the emergency was declared.

The audacity with which independent India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter opted for emergency rule was not a decision made on the spur of the moment. In 1971, she had written to a friend of hers bitterly complaining: “Our own press has done everything possible to mislead the public about me personally and about my aims and objectives. Even though everything they have said about my father earlier and then about me is being proved wrong all the time, the columnists continue with their supercilious analyses. The real trouble is that they have no depth or values.”

A few newspapers like The Statesman and The Indian Express resisted to the extent possible. Most others, including The Times of India, Navabharat Times, The Hindustan Times, Dinman, Current and Illustrated Weekly of India plus thousands of newspapers in the states and districts, defended the emergency as a “necessity” to save the nation from “foreign forces”. Khushwant Singh, who as editor helped boost the circulation figures of the Illustrated Weekly to a dramatic level, was vociferous in praising the prime minister whom he likened to Goddess “Durga astride a lion”.

Mana Ranjan Josse, then executive editor of The Rising Nepal, was on an assignment to help shore up the Nepal embassy’s information bulletin at Barahkhamba Road in New Delhi not long after the emergency. He called on a number of editors, including Girlal Jain of The Times of India and Nihal Singh of The Statesman. Most journalists were too scared to speak anything on current affairs and the emergency. Nihal Singh, however, stood out from the rest. He admitted that most of his peers were frightened of being tailed by intelligence agents and facing the prospect of sack orders by newspaper owners who generally were at the beck and call of the establishment.

Sharp scissors

For two and a half years of the emergency, press censorship acquired a notoriety that might now sound like a preposterous practice for the younger generations in India and the neighborhood. To save their own skin, censors put anything remotely smacking of criticism of the government on the chopping block. Partly to fill in the space thus created and partly to register their protest, newspapers carried contents on the origin of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, fossils of the ape man and the historical significance of different human settlements in ancient times.

Editorials and opinion pieces were left with an ugly blank space to convey to readers that it was the censors’ work. This put the emergency regime in unflattering light and attracted ridicule. Nepali journalist Shyam Bahadur KC, then city editor at The Rising Nepal, had been asked by Khushwant Singh to write about Nepal-India ties for The Illustrated Weekly of India. Confident of his connections with the Gandhi regime, Singh published KC’s story entitled “What Irks a Nepali about India.” Overnight, KC became a kind of celebrity in Nepal. Some days after its publication, Singh wrote to KC: “Your story has created a stir in the establishment here. But I like to needle them with such controversies.”

Movie-makers were enforced to submit free-of-cost copies of their new productions for charity shows to raise funds for Gandhi’s party. They took precautions to avoid the censor board’s fickle minds that ran riot with their scissors. Creativity was a grave casualty in not only cinema but all forms of fine and liberal arts. Today, were anyone to conclude that only during the emergency did the media in India face trying times under a wrathful government, nothing would be more removed from fact. Harassment and intimidation of the press is not an emergency exception in the world’s most populous multiparty polity. Down the decades, the mistreatment of the media continued.

Morarji Desai, Janata Party prime minister after the emergency was lifted and Gandhi’s party suffered a drubbing in the 1977 elections, ordered withdrawal of all government advertisements to The Times of India when an editorial in the paper angered him. His successors, too, upheld the tradition of overtly or covertly harassing the press. Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s slapped more than 100 cases each in the court of law against the The Indian Express and The Statesman.

Ethics and ethos

In 2016, the Committee to Protect Journalists counted 27 journalists killed in the course of their professional duties over a period of 15 years. It reported: “Only in one case in 10 years in India a suspect was prosecuted and convicted for killing a journalist but the suspect was later released on appeal!... The situation is truly alarming…No government in India has been an ardent champion of press freedom.” In the new millennium, paid news and interviews in the print and on broadcast media are extensive.

In a recent article, noted Indian author Sashi Tharoor, a ranking member of the main opposition Indian National Congress, commented on “India’s extraordinary media environment, in which the Fourth Estate serves as witness, prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner”.

Nepal is the only South Asian country to allow private radio stations to broadcast regular news bulletins since 1997. However, media organizations and prominent names in Nepal have at regular intervals expressed concern over intolerance toward the news media. National Human Rights Commission Chairman Anup Raj Sharma the other day spoke on the disturbing trend against the Nepali media. The main opposition Nepali Congress leaders have warned the Nepal Communist Party-led government against any infringement upon the rights of the press, though the KP Oli government is so far no different from Nepali Congress teams that we so often experienced for most of the years since 1990.