OR

Opinion

Bureaucratic Resistance on Nepal’s Path to Federalism

Published On: October 12, 2023 08:00 AM NPT By: Niyati Shrestha

Niyati Shrestha

The author is a researcher at Samriddhi Foundation, an economic policy think tank based in Kathmandu. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the views of the organization.niyati@samriddhi.org

More from Author

On September 20 this year, Nepal marked the eighth anniversary of the promulgation of the constitution. The Constitution of 2015 holds special significance as it was drafted by the Constituent Assembly, which brought about a major political shift in the country by adopting federalism as a system of governance. While the nation celebrated this significant day, around 2.5 million public school teachers took to the streets to protest against the recently-proposed Education Bill in parliament, expressing their dissatisfaction.

The dissatisfaction stems from provisions that would have transferred the authority of overseeing the appointment, transfer, and promotion of public school teachers to the local level. Clause 4 of Article 57 of the constitution clearly states that the secondary level education falls under the jurisdiction of the local government. Schedule 8, in relation to this article, has mandated the responsibility of basic and secondary level education to the local government. Despite all this, the public teachers have clearly refused to stay under the jurisdiction of the local level as they fear that the autonomous power to local levels might result in arbitrary transfers and promotions putting their jobs at risk. However, it’s not just job security that the teachers are scared of. The devolution of authority to local levels will weaken the unions’ ability to negotiate effectively on behalf of the teachers as they would have to engage with 758 local units instead of just one federal unit, putting their bargaining power at stake.

Since we are on the topic of the Education Bill, another debatable provision in the bill is the revival of the District Education Office (DEO). The process of federal restructuring initially led to the elimination of several district offices, including DEO, in order to transfer power to provincial and local levels. Different offices were established under the jurisdiction of the provincial governments to take over the roles of such eliminated offices, many questioned their relevance but due to lack of clearly-defined roles. This allowed the federal government to act on its own self interest and restrict the transfer of authority to subnational units. Moreover, district offices became convenient places for central authority to influence their power at the grassroots level given the federal level’s very limited capacity to dictate their own plans and programs at the local level as the local units are autonomous bodies.

The controversy of the Education Bill sheds light on complex dynamics and motivation of different stakeholders for blocking local authorities from exercising their power for their respective self interest. The dominant narrative surrounding Nepal’s federalism is that there is bureaucratic resistance from the federal level in terms of power devolution, and the protest from teachers has just supported this resistance.

On the topic of resistance, there have been several instances of resistance to power devolution from the federal government over the course of the transition period. For example, the absence of a Federal Civil Service law, coupled with a growing reluctance among bureaucrats to work in remote areas at the subnational level, has resulted in a shortage of employees. All of this has created an imbalance in the administrative structure of the country. Additionally, the police integration process remains incomplete despite the introduction of the Police Personnel Integration Act 2020. Furthermore, the amendment to the Nepal Police and Province Police Act last year that now allows Nepal Police to oversee security of the Kathmandu valley in coordination with Province Police, is nothing but encroachment on provincial levels’ independent jurisdiction. Moreover, the federal government has increased conditional grants to local governments while reducing fiscal equalization grants for the upcoming fiscal year. The initial purpose of conditional grants was to assist the sub-national governments in carrying out projects during the early years of transition and it was expected that these grants would decrease over time. But the exact reverse trend indicates that the central government is trying to assert its projects at the grassroots level, which contradicts the principles of federalism. These trends collectively indicate a growing level of bureaucratic resistance over time.

Historically, Nepal’s bureaucracy has functioned within a unitary system for a majority of its time. The bureaucratic resistance to the transition process should not be surprising. This resistance has simply increased on account of a clear political will on the subject matter. In fact, the present federal structure of Nepal, the number of sub-national units based on the territory and other constitutional framework was the result of strong bargaining and negotiation between leaders from political parties. However, the above mentioned amendment to Nepal Police and Province Police Act being passed from the parliament suggests that it is actually political leaders who have not been able to internalize federalism completely. The weak enforcement mechanism from political actors, in turn, has allowed bureaucracy to act on its own self interest, defying the principles of federalism. But, such strong resistance raises the concern about the future of federalism in Nepal.

The timeline of Nepal’s constitution-making process suggests that the inception of the idea, pursuit of federalism and the transition period has been shaped by the negotiations between different stakeholders. Therefore, the way forward appears to once again depend on negotiation and bargaining. Sub-national units must assert themselves and raise concerns about whether the federal level is delivering the promises of the constitution. For example, the Madhesh Province has been actively demanding autonomy, with multiple writs filed in court. Forums like the Inter-Provincial Coordination Division can be convenient places for other provinces and local units to raise the issue. Their bargaining efforts are what will bring federalism, the ultimate goal, into equilibrium, and only then can the country successfully transition into this new governance structure.

You May Like This

Federalism: learning by doing

Issues have emerged regarding effective implementation of federalism. But there is a long way to go and these issues can... Read More...

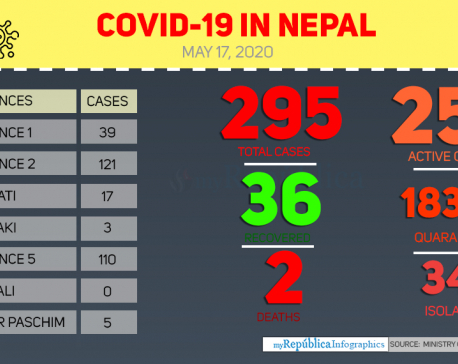

Health ministry confirms three new COVID-19 cases, number of total cases reaches 295

KATHMANDU, May 17: Nepal reported three new cases of COVID-19 on Sunday evening, taking the national tally to 295. ... Read More...

Dhurmus, Suntali to build ‘a Nepal within Nepal’

KATHMANDU, June 5: After successfully completing three settlement projects for earthquake victims and other communities, the actor couple Sitaram Kattel (Dhurmus)... Read More...

Just In

- NEA Provincial Office initiates contract termination process with six companies

- Nepal's ready-made garment exports soar to over 9 billion rupees

- Vote count update: UML candidate continues to maintain lead in Bajhang

- Govt to provide up to Rs 500,000 for building houses affected by natural calamities

- China announces implementation of free visa for Nepali citizens

- NEPSE gains 14.33 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.68 billion

- Tourists suffer after flight disruption due to adverse weather in Solukhumbu district

- Vote count update: NC maintains lead in Ilam-2

Leave A Comment