OR

Two recently published global indices embody the motionless in governance in the last two years. The first, Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), ranked Nepal 108th out of 141 economies it looked at in 2019. Nepal was ranked 109th last year and 108th two years ago.

Similarly, in the Global Hunger Index (GHI), Nepal ranked 73rd out of 117 economies, indicating serious hunger situation in Nepal. This ranking was 72nd in both 2018 and 2017 out of 119 economies they looked at. These two reports actually reflect what everybody in Nepal has felt in the last few years: Things are not moving.

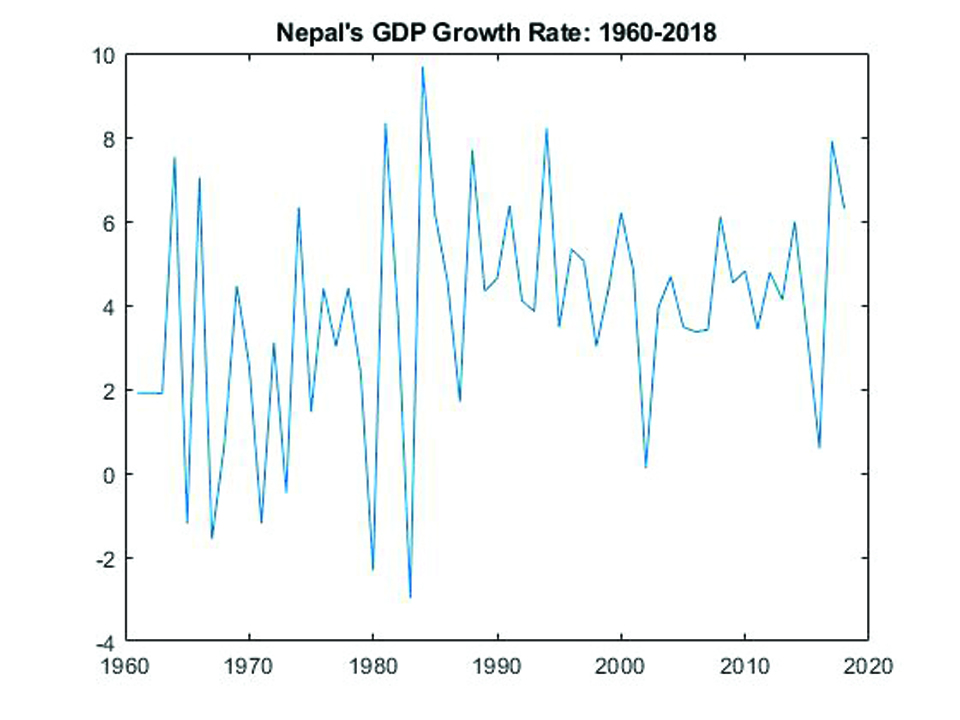

Inability to achieve any kind of momentum in almost all walks of life has been our collective weakness. This is also true in case of GDP growth. Nepal’s GDP growth rate fluctuated widely (see attached graph) in the last 60 years, never really gaining any sustained momentum. When things are good, we kill its catalyst and bring the situation back to usual level. When things are bad, somehow we bounce back. Our economic path is a random walk without a clearly identifiable trend.

Three reasons

Three important reasons are behind this static situation. One, failure to learn from our experience. Ministries don’t have good institutional memories due to excessive transfers of the bureaucrats. It is compounded by the almost lack of meritocracy in promotion. Those a bit courageous often found themselves embroiled in the controversy as hyperactive journalists tended to mercilessly report even the acceptable flaws in their undertakings. The last two reasons have dissuaded almost all bureaucrats from trying new things.

Examples abound. Those who worked hard to bring Arun III were branded anti-environmentalist and pro-World Bank. Those who worked hard to make Kathmandu-Nijgadh expressway not only saw the project downgraded and awarded to the military, but also found themselves accused of being pro-India. In this system, as the ministries saw many ministers being changed too frequently, the best response of a bureaucrat to existing situation has been to do nothing, bide their time, and they could always claim seniority and be automatically promoted.

The absence of technocratic leadership that identified long term bureaucrats and promoted them on the basis of their performance was missing from our governance since long and it made learning within the ministry a rare and often undervalued quality among bureaucrats. Absence of learning meant we did not know when we were in good times, and could not create momentum by pressing home our advantage.

Second, failure to draft a long term vision and stick to it. Our five-year plans started to become a joke during the period of civil unrest. The 14th plan doesn’t even have English version because, as a senior respected bureaucrat once told me, it was already too embarrassing to have it in Nepali. The plans were often mumbo jumbo, copy and paste of inputs received from different ministries.

Furthermore, long-term plans are for peaceful stable time. The civil unrest increased uncertainty and limited everyone’s vision. Furthermore, even in peaceful days, good plans are not drafted for two reasons—absence of good planners and absence of willingness to execute these plans. In our case, mostly both reasons were in existence.

The quality of planners working at the National Planning Commission (NPC) started deteriorating in the last two decades, and the NPC leadership often found it difficult to cooperate with the Commission’s own bureaucracy, let alone with the bureaucrats from other ministries. On the other hand, the political leadership which appointed the commissioners does not feel the need to take any suggestions from them. The failures to have a long term vision and people working to achieve a common goal are reflected in the performance in indicators such as GDP growth rates.

Third, absence of true agents of change. Though political leadership in Nepal was often voted to power with the hope of sweeping changes in status quo, and indeed that is what they generally promised before the election, they become a true conservative after their ascent to power. Our leaders’ idea of change is to replace the ruler and not the system. This is true for bureaucracy as well. There are very few champions of reforms within the bureaucracy.

I sometimes read in the documents of donor agencies that they would like to support the champions of reform within the ministries. Their ability to do so is actually very low. The absence of people who want to do things differently is common in all other layers below the political and bureaucratic layers. Contractors, engineers, local level government representatives and all others responsible for transforming the country generally want to continue what they are doing, but hope that other agents change their behavior.

These are the major reasons why important transformations do not happen. Once in a while important initiatives are proposed though they often meet the same fate. My favorite example is a massive reform for general administration proposed by Kashi Raj Dahal Commission in 2016. It pointed out the necessity to reform the structure, working style and evaluation system within the bureaucracy. Many experts also suggest that our bureaucracy is oversized.

In 1991, a commission formed by the then Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala recommended 15 to 20 percent reduction in the size of government bureaucracy. Perhaps the same is true at this stage as well. The Dahal commission is still awaiting the implementation and further research on its recommendations despite getting parliamentary support.

Hurdles to reform

Why do not administrative reforms materialize? Our current leadership does not have a good track record when it comes to austerely running the government. In 2008, Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal increased the number of ministries from 22 to 25. In 2015, Prime Minister KP Oli increased the total number of ministries from 27 to 31. The opposition leader Sher Bahadur Deuba was also notorious for increasing the size of his government.

It is therefore unlikely that major administrative and economic reforms will happen soon under current leadership unless their attitude changes drastically. It is sad because not long ago all these three were considered revolutionary leaders who were willing to risk their lives to change the country. Costly governments and apathetic bureaucracy jointly affect the economic environment in the country, and makes it mandatory to keep tax rate high.

As we await the score of Doing Business Index this week, we already know that if we need to change things appreciably, the primary agents are our bureaucrats working under visionary leadership. Even if our score increases this year, it will not be sustainable unless backed by conviction of people leading the ministries.

The author is an economist

You May Like This

Think beyond roads

In an egregious case of ‘dozer terror’ in Baitadi, the District Police Office has arrested the driver of the excavator... Read More...

NPC finds local levels putting all budget on infrastructure

KATHMANDU, Jan 6: National Planning Commission (NPC) has identified that the local bodies have failed to allocate the budget to all... Read More...

Infrastructure development to advance villages: Minister KC

KATHMANDU, Aug 26: Minister for Urban Development, Arjun Narsingh KC, has said development of physical infrastructures in rural areas was... Read More...

Just In

- Challenges Confronting the New Coalition

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

Leave A Comment