Having completed revising academic materials for an examination, on a sunny day in 2014, I found myself bewildered by a question I had no method to answer: “What effect does our naming of objects and concepts have on their meaning?” Simply put, what if the real name of gravity is not gravity? Are we, as the human race, actively conceding an error by naming concepts and objects wrongly, affecting their meaning in the process.

If not through understanding, then perhaps via empathy, it can be deduced that it is not only I who is disturbed by their inability to tackle such a question out of sheer intuition. Times numerous, we, as individual entities of the human kind, find ourselves facing questions that transcend our material knowledge. At times, the questions are as simple as ‘What is god?’ and other times, questions more fundamental, ‘What do we know that we can ascertain?’

Questions anywhere on the spectrum of wonder to rigor, pertaining to our knowledge of ourselves as the plethora of phenomena that occur around us tend to fall under the ever-expanding, headstrach-inducing field of philosophy. The middle English terminology ‘philosophy’ originates from the Greek word philosophia, philo meaning love and sophia meaning wisdom, culminating in the meaning of the terminology as ‘love of wisdom’.

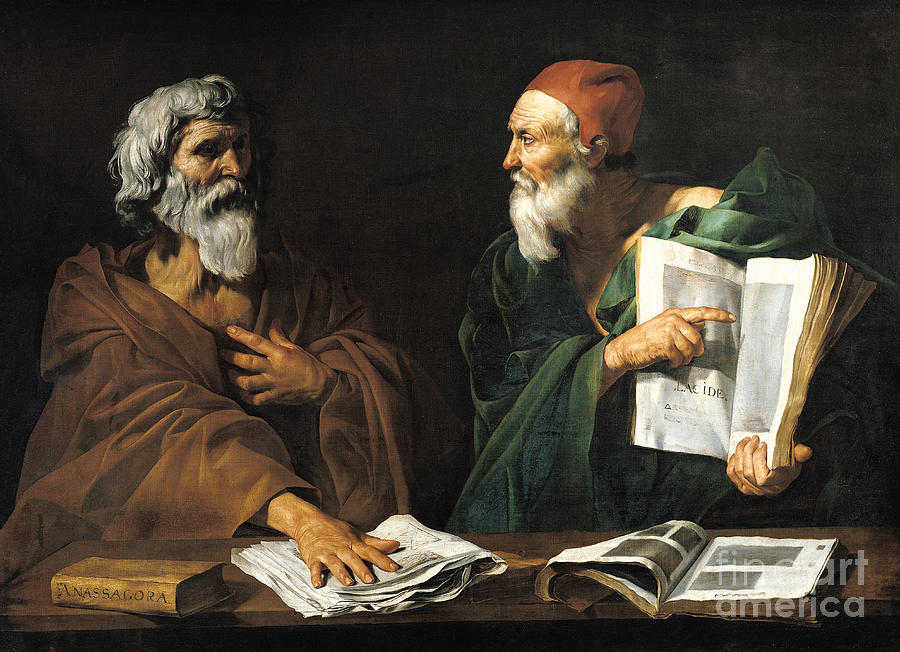

In ancient Greece, from where philosophers start their inquiry of the self and the world, the common conception in the thinking class was that philosophy starts with wonder. As Socrates duly noted while conversing with Theaetetus in Plato’s The Theaetetus, “This sense of wonder is the mark of the philosopher. Philosophy indeed has no other origin…” Aristotle concedes to this notion, emphasizing intellectual curiosity. In Metaphysics, he stated that it is due to our wonder that we philosophize and at first began to philosophize.

Books to get you started on philosophy

Millenia later, David Hume, another empiricist, cast doubt into the fray, laying skepticism as the foundation of his philosophy. German Transcendentalist Immanuel Kant, claimed that awe of the cosmos and morals sets us up on the journey to wisdom. In his magnum opus Critique of Pure Reason, the rationalist wrote, “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe… the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.” Both of these accounts, albeit their radically contrary understanding, added elements to the foundation of wonder without necessarily refuting it.

Pessimistic existentialist Arthur Schopenhaur set suffering as the starting point, rejecting the foundation of wonder while G.W.F. Hegel superseded the role of wonder by emphasizing historical reflection. Hegel states in Preface to the Philosophy of Right, that ‘Philosophy is its own time comprehended in thought’. More Recently, Ludwig Wittgenstein, the maestro behind the linguistic turn of philosophy, stated in his magnum opus Philosophical Investigations, that philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language, thereby shifting the centrality of philosophy to sufficing the inadequacy of language.

Antiquity’s fixation on wonder and thereby to question, albeit the recent diversions, seems to be the first step in the human quest in the love of wisdom. As highlighted, philosophers, the tribe of greatest head-scratchers and pensive chin-on-hands, have spent millenia on the seemingly simple question, “Where does philosophy start?” and are yet to reach an objective answer.

If we cannot answer one question objectively, thereby leaving us stranded on the question of wisdom, then what is the point of philosophy? But it is not just one question, as students of philosophy explore the swamps of existing philosophical knowledge, they find that most if not all questions in philosophy have no objective answer. So what is the point of doing philosophy?

Firstly, philosophical reading provides us the platform to question our intuitions, increasing our capacity for critical thinking. By first interacting with a work of philosophy that resonates with our intuitive understanding, we validate our intuitions. Then, by reading more on the same topic, we get to analyze whether our intuitions would still stand in the face of crushing opposition. Doing so, we provide space for criticism and propagate critical thinking.

Beyond critical thinking, the activity of philosophy, as stated by Wittgenstein, shifts us closer to understanding our own questions by unrooting the ambiguity in our language when we state complex terminologies. By philosophizing, we sharpen human language.

Since philosophy also pertains to leading our life, it has always been used as a tool to discover the “good life”. Through its direct implication on ethics and morals, which in turn dictate social sciences such as politics and economy, philosophy directs human society on the search for the good life.

The absence of objectivity in philosophy, therefore, need not be undertaken as a blight on the otherwise beguiling field. If it offers solace, more recent philosopher Richard Rorty has even attempted to shift the focus of philosophy away from objectivity and towards human solidarity. There is a certain sense of relief for young philosophers in Rorty’s claim that philosophy is about conversations–dialogues, discussions of debates–rather than finding objective answers.