OR

More from Author

Processing of household and commercial waste close to their point of origin should be our priority

Municipal solid waste (MSW) management is a challenge for the urbanizing world, especially in developing countries, where economic development, expansion and rapid urbanization have significantly increased the generation of MSW. The large volume of MSW requires sustainable management. The majority of waste is currently disposed of in landfills, from where it emits landfill gas (LFG) containing methane, a substance that makes a big contribution to global warming. It also produces leachate, a liquid containing toxic compounds that disperses through the soil in and around landfill areas. Waste, together with emissions from waste water, account for about 3 percent of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Nepal, as reported in 2012.

The MSW generation in urban cities of Nepal is about 1,435 tons per day, as reported in 2013, of which about 60 percent is from households and the rest from institutional and commercial sectors.

Increasing waste generation is a trend associated with urban population growth. The wastes contain, primarily, decomposable components, which make up about 70 percent of household-sourced waste and about 40 percent of waste from other sectors. There is therefore scope to significantly reduce municipal waste if it can be properly managed at the household level.

The best option would be to use anaerobic technology to convert decomposable waste into biogas.

Several studies suggest that resource recovery of waste is a viable option for management of degradable organic component of waste, as compared to dumping and/or land-filling all waste streams. Land-filling of energy-rich waste should be avoided as it has several negative environmental impacts, such as loss of a valuable resource, extra cost required for leachate treatment and for the closure of a land-fill site.

Nevertheless, conversion of decomposable solid waste into biogas has not yet been successfully realized in Nepal, though efforts have continued for many years. Management of decomposable solid waste at the household level using “Sahari Gharelu Biogas plant” (which is essentially an ARTI model developed in Indian context) has not been widely accepted and the waste plants they were installed in do not function well. Similarly, efforts to manage waste at community level or at central point by installing relatively large biogas plants have not delivered encouraging results, except in initial few weeks or months of installation.

It is again pertinent here to consider one of the simplest digester designs, the Sahari Gharelu biogas plant, which is made from plastic tanks, similar to those used for water storage. Why is it not functioning well in Kathmandu and other urban areas in Nepal? The simple reason could be that the plant is a simple plastic tank which works well in Central India with a temperature climate, but not so well in Kathmandu.

Transfer of technology is a good idea, but adequate attention must be given to the science involved. An inadequate understanding of the science behind the technology results in discouraging outcomes. Research and development is required for this understanding, so that technology can be modified to suit local conditions.

Lack of research and development has been an issue with biogas plants fed with animal manure and human sewage. The biogas program in Nepal has been both successful and acclaimed. The installed plants use animal manure as the main feed, although latrines for human sewage are often added as well, and over 300,000 plants have been installed. The program was able to obtain credit through the clean development mechanism nearly a decade ago, when there was a good market for carbon trading. However, the program is based on a design of biogas plant—the GGC 2047—which was developed well over 30 years ago.

Only minor modifications have been made since the design was finalized in 1991. However, despite this long history of extension of this successful domestic biogas plant, there are few research publications and reports on technical issues that can suggest further improvements and modifications. For example, research has demonstrated that digester and gas stove designs used in these plants in Nepal are not efficient, but there has been no comprehensive research to improve on the design as well.

In this context, it is high time to review past and current efforts of waste management and waste- to-energy models in Nepal. The concerned agencies must make an effort to discover why their efforts at waste managing have failed. Is it a problem with policy? Is it a problem with technical knowhow? Is it a problem with our organizations? Or is public indifference the problem? After proper analysis, they must come forward with a scientific solution. In order to find the best way to process waste and convert it to energy, they need to generate an effective scientific understanding of the processes involved.

There is a need for more research and development, both by national institutions, but also with the support of international partners. The most effective solutions will involve the private sector, as the answer must be financially sustainable. Discussions with local and international agencies suggest that they place low priority on research and development. They would rather prefer to waste huge amounts of money on solutions that are inappropriate and ineffective in local situations. This mindset must change.

There is a need to give high priority to processing of both household and commercial waste close to the origin of such waste. This would reduce the need to transport and dump more than 60 percent of the waste that presently end up as MSW. The government needs to provide incentives for local waste management, such as through tax reductions and other social benefits. Commercial companies could earn good income by converting energy-rich waste into fuel and compost, given the right socio-economic climate. Right technology needs to be developed and people need to be better trained on how to employ this technology.

Lohani is Assistant Professor at Kathmandu University and Fulford is Director at Kingdom Bioenergy Ltd, UK

splohani@ku.edu.np

You May Like This

Locals threaten to obstruct dumping of garbage in Banchare Danda from August 17

KATHMANDU, July 28: The locals of Banchare Danda have announced that they will not allow the Kathmandu Valley’s waste to... Read More...

KMC working on vending machine concept for waste management

KATHMANDU, Mar 27: The Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) Office is learned to have been working with the concept of placing vending... Read More...

Bio gas to be yielded from human waste collected from Everest base camp

SOLUKHUMBU, April 13: Bio gas is to be produced from human fecal matter collected from the Mount Everest base camp... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

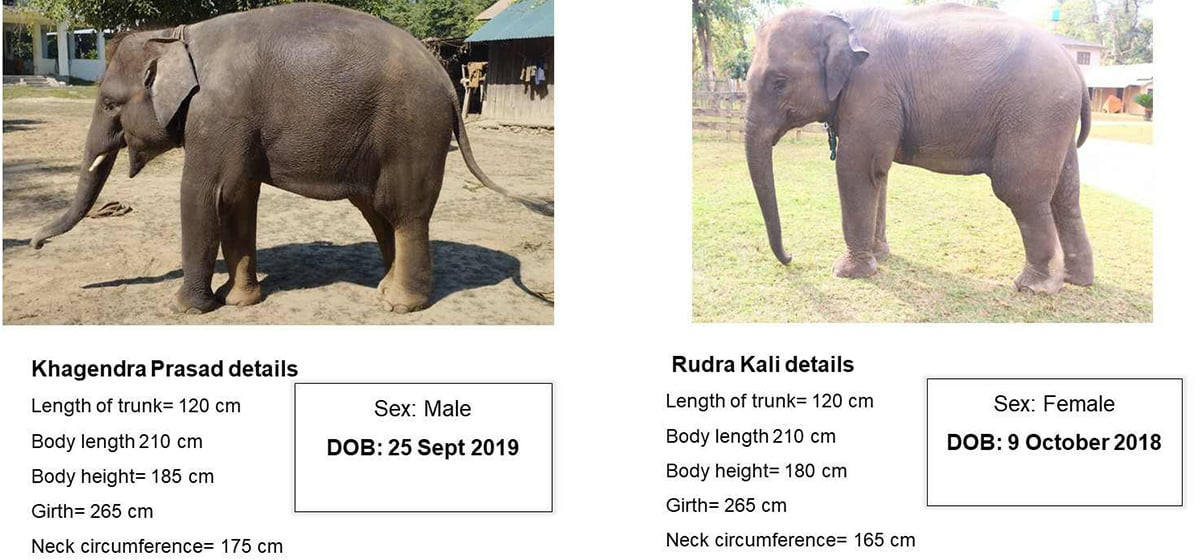

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to help secure release of Bipin Joshi held hostage by Hamas

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

- Devi Khadka: The champion of sexual violence victims

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment