British voters have roundly rejected Theresa May’s call for a “hard Brexit,” in which the UK would leave both the EU single market and the customs union.

NEWTON, MASSACHUSETTS – Britons who already realize that the United Kingdom cannot possibly withdraw from the European Union without incurring substantial economic costs were undoubtedly disappointed by their country’s recent general-election campaign. The leaders of Britain’s major parties showed that they have neither a coherent plan for Brexit, nor the courage to reject it.

It is time to hand leadership to an experienced, clear-eyed leader who can dispense with tribal politics and cobble together support from the sensible wings of the major political parties. That leader should be Kenneth Clarke, the current Father of the House.

Prime Minister Theresa May has proved incapable of leading the Conservative Party or the country. After calling an unnecessary snap election, she ran an incompetent campaign that left her government dependent on the dubious support of the right-wing Democratic Unionist Party. British voters have roundly rejected her call for a “hard Brexit,” in which the UK would leave both the EU single market and the customs union.

Moreover, May’s ministers, not least Boris Johnson and David Davis, have proved inarticulate and ill-suited to meet the serious challenges that await the UK. Given their many failures, and hers, May should already have been ousted as party leader and prime minister. How much longer she can remain in power is uncertain, to say the least.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn is no better. Despite Labour’s official support for the “Remain” campaign, Corbyn himself never expressed any strong commitment to that outcome. During the recent election, he said little—and proposed even less—concerning Brexit, even though it is the most consequential economic challenge Britain has faced in more than a generation. Corbyn’s hard-left tribalism and domineering leadership style have resulted in numerous dismissals and resignations from Labour’s front bench, and have driven some talented Labour MPs away from party politics altogether.

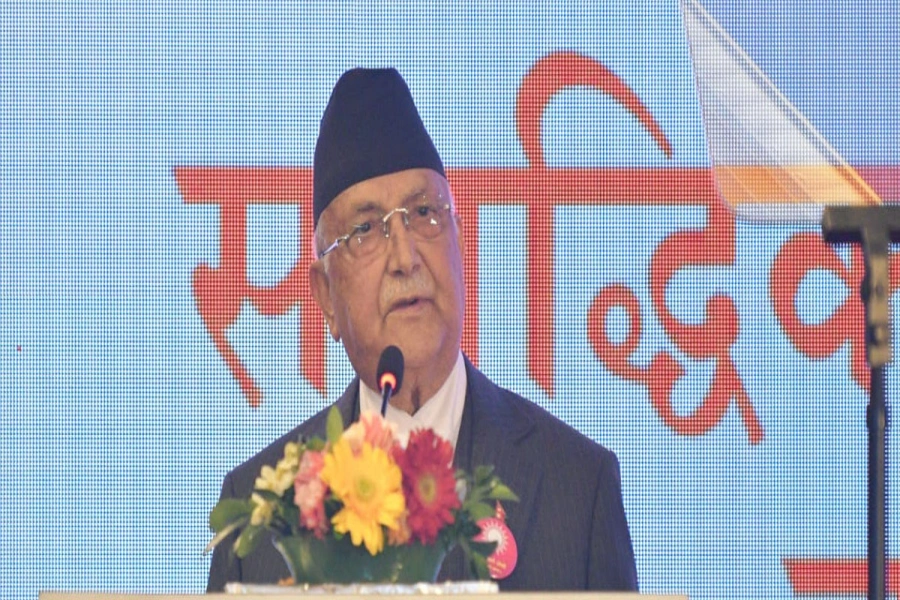

Chief characters in Britain's Brexit saga

Although Labour gained 30 parliamentary seats in the recent election, it still trails the Conservatives by 54 seats, and is more than 60 seats short of a working majority. Still, the election was hardly a disaster for Labour, which had trailed the Tories by more than 20 points when May called the election. And, because Corbyn remains popular with rank-and-file party members, he will likely hold on to the party leadership for the foreseeable future. In fact, given the Tories’ sorry state, Corbyn could even become prime minister, albeit one without the full support of many of his own MPs. That outcome would be a disaster.

The Brexit referendum seems to have been drafted by someone who expected it to fail: the wording really only made sense for those voting “no.” As we now know, a “yes” vote introduced deep uncertainty, because it provided no guidance about what voters actually want. It is unclear whether “Leave” voters hoped to withdraw from the customs union, limit the free movement of EU citizens, or free themselves from EU regulations. Pollsters can speculate about the answers to such questions, but there really is no way of knowing voter intent without administering a detailed, multiple-choice questionnaire. In the end, it will be up to Parliament to decide what sort of Brexit—if any—to enact.

Given the enormous challenge Brexit poses for the UK, Parliament should respond as it would to a war or other national emergency, by forming a unity government with a fixed term expiring shortly after March 29, 2019, when the UK will have formally left the EU, deal or no deal. A national government of this kind could bring sensible Tories, Labourites, and Liberal Democrats together to determine how Brexit should proceed.

Clarke is the right choice to lead such a government. He is respected on both sides of the House of Commons, and belongs to the party with the most seats. As a former chancellor of the exchequer, he has the experience to address what is largely an economic issue.

Like a majority of MPs, Clarke opposed Brexit; but, unlike most of his Tory colleagues, he followed his conscience, and voted against the Brexit bill when it came before Parliament in March. Under a national unity government, Clarke could assemble a cabinet of soft-Brexit Tories and moderate Labourites to take a cold, hard look at the UK’s current options. They may determine that some form of soft Brexit is best for the country; or they could decide to abandon Brexit altogether.

Under this framework, Clarke’s premiership would be far shorter than that of Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair. He would not stand in the way of younger MPs who want to pursue the top leadership spot in the near future, because, unlike May and Corbyn, he has no motivation to cling to power. In all likelihood, Clarke, who had planned to stand down from Parliament in 2020, would get the job done and move on to the House of Lords with the thanks of a grateful country.

The hardest part about this plan would be finding talented MPs who are willing to risk the ire of their colleagues by joining a politically diverse coalition. One hopes that the looming Brexit deadline will convince MPs to put country before party, and to make Clarke prime minister.

Richard S. Grossman, a professor of economics at Wesleyan University, is the author of WRONG: Nine Economic Policy Disasters and What We Can Learn from Them.

© 2017, Project Syndicate

www.project-syndicate.org