Speak, it is your own tongue.

Speak, it is your own body.

Speak, your life is still yours.”

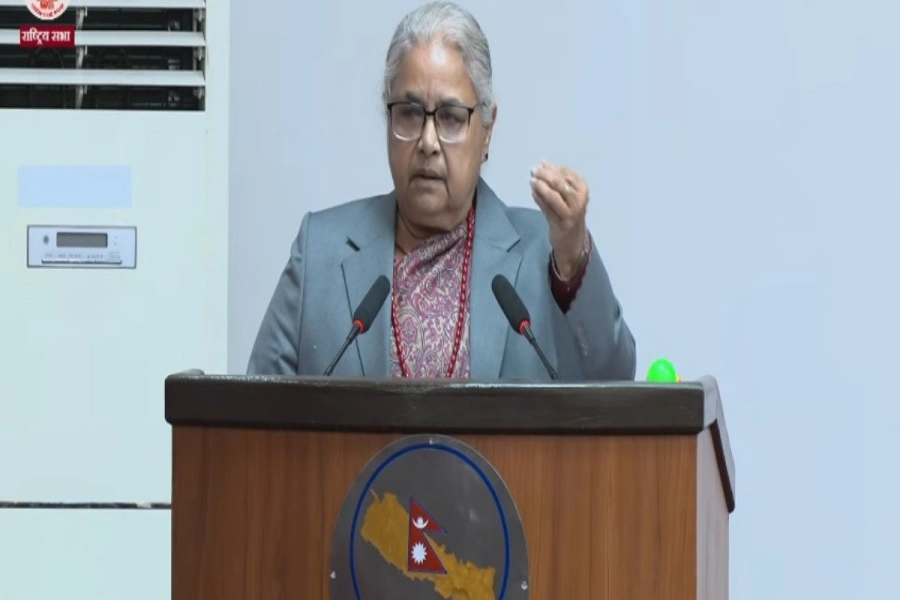

Burrowing from the late Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s ‘Speak’ was how Indian actress at-large Shabana Azmi wrapped up her opening address for the four-day long Film South Asia ’09, the region-wide biennial documentary festival that kick started in the Nepali capital yesterday.[break]

Talking to Republica in an exclusive interview, Azmi who is known for her fierce on and off screen activism says, “Art should be used for social change as it creates a climate for change to occur and impact ways to create transformative points.”

The acclaimed actress, who first came to Nepal in 1974 for the filming of Dev Anand’s “Ishq Ishq Ishq”, staged the acclaimed play ‘Tumhari Amrita’ together with Farooque Shaikh on 16 September as part of a fund-raising drive for the Spinal Injury Rehabilitation Centre (SIRC).

For her, art is not something that’s divorced from life. “Arts is life, my resource base as an artist is life itself and that’s where I draw my power, my strength and my associations from,” says Azmi whose works are considered to be one of the most path-breaking films in Indian cinema and not Bollywood because “the word Bollywood is actually an in-house joke” that is a plagiarized version of Hollywood and “that’s just not true.”

“There are no two separate parts of my life,” she says. So she can’t say whether she is an artist or a person with other lives. “Life happens and from it I draw resources to do my work as an arist. There are no two separate two entities,” she adds.

From her powerful acting in movies like ‘Masoom’, ‘Arth’, ‘Mandi’ and recently released ‘Morning Raga’, ‘15 Park Avenue’ and ‘Honeymoon Travels Pvt. Ltd’, Shabana Azmi who can now even be seen selling washing powder and walking the ramp, was once the leading actress of the now largely defunct (presumed) art-cinema in India.

This presumption, however she likes to clarify is false. “That’s not true at all,” Azmi says, and tries to adjust a comfortable position to rest her back sprain which she got on her flight to Kathmandu. Our conversation comes to a halt.

For a moment there.

The Film South Asia conceiver Kanak Dixit asks if she could be provided with a hot water bag.

Azmi reminiscence the earlier filmmakers she worked with including Shyam Benegal and Satyajit Ray and how they were involved with rural India, making a league of parallel cinema possible then.

“All of them were affected. Today’s filmmakers are city-going western-educated English speaking young men,” she reflects.

The problem with that crowd is they reflect problems that are about their angst and their concerns. “But some are doing it, many of them, in independent films which are being made, which may be not about rural India but are not really cowing down to the market. So I believe a host of independent films have been made which to me are today’s parallel cinemas,” she continues, a little wary on the presumption made.

But what are Azmi’s views as far as the rhetoric goes that social change is possible through art?

“It’s not like a litmus test. You can’t put in pink and blue. Art can create a climate of sensitivity in which it is possible for change to occur,” she says. “For instance, documentaries have this certain rawness and certain passion and a certain directness…they can suck you in the face and get a reaction which is very strong. There is a complete direct appeal…they have a transformative quality to them, which is much more direct than if you try to seek it through feature films or through literature.”

For Shabana Azmi, the most important part of her craft is the language. “If I use painting as my medium, I better be good at that craft,” she is a conformist when it comes to art. And it’s evident since she hails exclusively from an artistic family. Born into a Muslim family, her parents Kaifi Azmi, a renowned Indian poet and Shaukat Azmi, a well known stage actress have been pivotal in her upbringing and the rich influence which is to her like a heritage. “I am a product of my background,” she says, whose hubby, Javed Akhtar, is the most sought after lyricist in India and son Farhan Akhtar, the leader of new generation of Indian directors (and actors).

Her father was a member of the communist party. “And I and my brother grew up in a kind of a commune like situation and my mother used to take me with her on tour of the Indian People Theater Association, so it was only natural that I would gravitate towards both these strains, commitment to social issues and interest in the theater and the arts,” says Azmi whose role in real life, than the movies, is her biggest —as a tireless crusader.

But the crusades haven’t been easy for this five-time winner of India’s prestigious National Film Awards who easily switches from her roles of glam Bollywood heroine to that of an oppressed villager. Her on and off screen activism has landed her in a lot of controversies as she continues her commitment to fight against AIDS, religious fundamentalism and social injustice in real life.

A vocal socialist, Azmi who is also the SAARC Goodwill Ambassador for Uniting against HIV/AIDS and TB has participated in several protests programs denouncing communalism. In 1989, she undertook a four day march along with Swami Agnivesh for communal harmony from New Delhi to Meerut.

“I remember when I was preparing for the march, how there was a lot of tension in the house and my mother was so worried and I went to meet my father who has a very strong influence in my life,” she adds, “he just looked at me and said - “Oh! My brave daughter is getting scared. Go and you will come back successful” - and for me it was like a burst of oxygen that I got.”

And there have been several other occasions where Azmi has advocated for a host of other social issues, notable among which is the five-day hunger strike that she had undergone to advocate the right of shelter for slum dwellers.

“Anand Patwardhan’s ‘Bombay our city’ really got me involved in Nivara Haak, an organization which works with slum dwellers in Bombay,” she adds, “We’ve built 12,000 home for free for slum dwellers in Bombay which is the largest single rehabilitation project in Asia of which we are very proud.”

Azmi staunchly opposed the call by an Imam upon Indian Muslims to join the jihad post 9/11 attacks and suggested the leader to go alone. Her forceful criticism of religious extremism post 1993 Mumbai riots help build communal harmony and religious tolerance.

Earlier this year, Azmi was conferred with the International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) Global Leadership Award at Macau on Friday, June 12 for her hard work in denouncing AIDS and communalism and improving lives of slum dwellers.

“During the hunger strike, my mother wrote to my father saying how my blood pressure had fallen and all but father simply replied, “Best of Luck, Comrade” and I felt very heartened by that,” she smiles as she shares with us another anecdote.

“I once asked father, “When you are working for change don’t you get frustrated when it doesn’t occur at the pace you want it to be?” and he said, “When you work for change you should build into that expectation that the possibility that the change might not occur within your lifetime but have the faith and the belief that if you carry on working regardless, then that change will come if even it comes after you. And then there will be no place for frustration.”

“That to me is my ultimate mantra when it comes to Kaifi (her father),” concludes Azmi who turns 59 today.

And the crusader fights on…

Shabana Azmi to pen a memoir