OR

The dangers within

Published On: August 8, 2018 01:30 AM NPT By: Bikash Sangraula | @SangraulaBikash

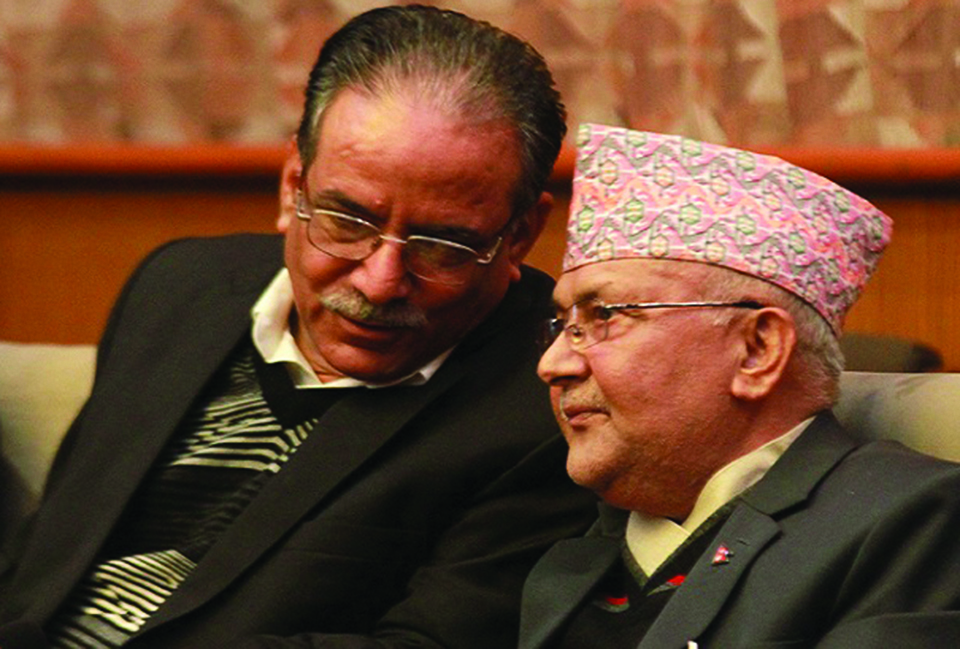

Real threats to the government of K P Oli, if they emerge, will emerge from within his own party

It has become increasingly difficult to recognize, in his second stint as prime minister, the Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli who won the trust of the nation during his first stint. Still, few would disagree with Mahabir Paudyal’s argument in this daily last week that Oli must not fail (See “Warning on the wall,” Aug 2). Nepal’s political process has unfolded in such a way that Oli’s failure won’t just be a politician’s personal failure. It will have broad and lasting national ramifications.

The question, then, is: Will he fail? The answer is: He may.

Imagined Threats

Many of the threats that Oli’s government is rumored to be facing, or expected to face are just the products of fertile imagination.

Nepal Communist Party lawmakers’ fondness for terming almost everything, including rape, as a ploy to topple the government is, to be polite, an indulgence in outrageous gaffe. A harsher way to look at it is to liken it to a particularly treatment-resistant strain of paranoia acquired during almost three decades of astonishingly frequent government changes.

The government enjoys more than a comfortable majority, cemented after the merger in May of erstwhile CPN (UML) and CPN (Maoist Center). It is, therefore, in the interest of paranoid NCP lawmakers to remember that, as things stand, the possibility, in percentile, of this government being toppled stands at zero. Hark!

Also in May, Oli demonstrated political foresight by inducting Federal Socialist Forum-Nepal in his cabinet. While some interpreted this as a stratagem to further weaken an already toothless opposition, FSF-N’s induction serves the government the important purpose of pre-empting fresh trouble in Province 2. With Upendra Yadav by Oli’s side, this possibility has been considerably, if not completely, neutralized.

The main opposition, Nepali Congress, is too feeble, too worn out, too divided, and too wanting in agenda to remotely pose a threat to NCP’s grip on power.

Despite some setbacks—principally over the West Seti project, and inability of Nepal and China to finalize a transit and transport protocol last month—Beijing’s love affair with Oli, which flourished during his first stint as premier, is still going strong.

What about our southern neighbor?

Having learned not long ago that its political and geographic biceps and triceps don’t intimidate Nepal, New Delhi is unlikely to upset the new equilibrium to which ties have returned after a period of ill-will that was disastrous to New Delhi’s reputation in the region.

Unless Indian National Congress figures out a way to pull off what Imran Khan recently did just across the LOC, Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party will most likely win general elections in India next year. With Modi again at the helms, he will be no exception, vis-à-vis New Delhi’s Nepal policy, to the old proverb: once bitten, twice shy.

Real Threats

Real threats to Oli, if they emerge, will emerge from within. And by within, I mean his own party.

Ever since the merger with former Maoists on May 17, Nepal has been practically ruled by two prime ministers. One pulls some of the strings, not all. The other shoulders all the blame, not some.

Were it not for Pushpa Kamal Dahal, Oli would have no reason to recommend presidential pardon for Bal Krishna Dhungel, and shoulder all the blame for it. Were it not for favors Dahal owes to Durga Prasai, Oli most likely wouldn’t have allowed his own popularity to plummet so much by unnecessarily prolonging Dr Govinda KC’s hunger strike until relenting completely. Oli lost considerable political capital in both the cases. Dahal, on the other hand, got what he wanted in the first case. Although the second didn’t go the way Dahal wanted, he didn’t lose anything.

Oli needs Dahal to keep the government intact. Dahal politically extorts Oli for this ‘favor’ because, as the saying goes, old habits die hard. Dahal’s own survival as a politician depends, as much as his political reinvention did in last year’s general elections, on Oli—a fact that seems, for some reason, lost on the official prime minister.

It remains to be seen to what extent Baluwatar’s seemingly all-powerful occupant will allow this political extortion to continue. To what length will Oli go to exonerate Dahal and his now ‘reformed’ comrades of the brutalities they committed or orchestrated in the past is unclear. Some indications, though, are worrisome.

On June 12, the Oli-chaired Constitutional Council recommended Deepak Raj Joshee for the post of chief justice. By a curious turn of events that sent the rumor mills into overdrive, Oli then flip-flopped. At the behest of both the official and unofficial prime ministers of the country, the Parliamentary Hearing Special Committee accepted as inviolable truth a news piece carried by an influential newspaper questioning Joshee’s academic qualification and rejected Joshee last week without even bothering to probe whether Joshee is indeed unqualified.

The rejection of Joshee, cheered by many on social media, raises some fundamental questions about the state of democracy in Nepal. Nepal’s parliaments, present and past, haven’t sufficiently proven that they are capable of acting independently of the executive. That some Parliamentary Hearing Special Committee members—of the ten members who last week rejected Joshee—have said on record that they were waiting for Baluwatar’s position to take a decision on the matter, is telling.

Now that Joshee has been rejected, even the most paranoid members of NCP must have realized how powerful the executive is. The prime minister, for whatever reasons and for whoever’s interests, can dictate parliamentary committees to reject his own recommendation, without having to answer questions regarding why he made the recommendation in the first place.

Justices, henceforth, will not only have to be mindful of the need to be in the good books of Baluwatar to get promoted, but will also have to constantly remind themselves that the Sword of Damocles—more popularly known as impeachment in this context—hangs above their heads.

In essence, separation of powers is practically non-existent. Nepal’s version of democracy, known as loktantra, now has just one all-powerful pillar—the executive—before whom the legislature and the judiciary cower.

Given this state of the state, ambitions will surely rise in the lairs of executive power. There is ample time for those in, and close to, power to flirt with the idea of taking a leap into the unknown.

Authoritarianism, which has so far proven a scarecrow used unsuccessfully by the Nepali Congress during last year’s election campaign and even thereafter, will gradually grow into a strong temptation.

The unofficial prime minister, whose ambitions know no bounds, will sooner or later nudge the official prime minister to give in to this temptation. Giving in will guarantee an implosion of the NCP-led government. The Nepali populace doesn’t tolerate authoritarianism under any guise, and is remarkably gifted in the art of punishing such regimes.

Oli, who has witnessed time and again the unenviable fate faced by such regimes, must be mindful that such temptations have to be nipped in the bud.

Another real threat to the government is Oli’s health. Rumors and reports, including a recent interview of Oli’s wife Radhika Shakya, suggest Oli’s health is failing him. If the eventuality that none of us can escape befalls Oli in the next four years and seven months, the balance of power and hierarchy delicately maintained by the gargantuan political party—NCP—will vacillate in unpredictable ways.

If I weren’t an atheist, it is possible I would dedicate one of my prayers exclusively to Oli’s good health. Not because he is someone I idolize. I would have very pragmatic reasons for the hypothetical prayer.

First, I don’t see a better replacement. Second, I believe Oli hasn’t become oblivious of the fact that history has presented him with the opportunity to be remembered kindly for a very long time. On the flipside, the same opportunity, if squandered, can guarantee that he is forgotten quickly. I believe he will choose the first option.

If governments were judged by their performance of five months, they wouldn’t be elected for a five-year term. Health permitting, Oli has plenty of time to rediscover himself and leave behind an enviable political legacy.

Sangraula is a journalist and author based in Kathmandu

Twitter: @writerbikash

You May Like This

Exploring opportunities and Challenges of Increasing Online Transactions in Nepal

Recently, I embarked on an errand for my parents. Upon completing my purchases, I proceeded to the checkout. The cashier,... Read More...

Why Federalism has Become Risky for Nepalese Democracy

The question arises, do federal or unitary systems promote better social, political and economic outcomes? Within three broad policy areas—political... Read More...

Nepal's Forests in Flames: Echoes of Urgency and Hopeful Solutions

With the onset of the dry season, Nepal's forests undergo a transition from carbon sinks to carbon sources, emitting significant... Read More...

Just In

- Godepani welcomes over 31,000 foreign tourists in a year

- Private sector leads hydropower generation over government

- Weather expected to be mainly fair in most parts of the country today

- 120 snow leopards found in Dolpa, survey result reveals

- India funds a school building construction in Darchula

- Exploring opportunities and Challenges of Increasing Online Transactions in Nepal

- Lack of investment-friendly laws raises concerns as Investment Summit approaches

- 550,000 people acquire work permits till April of current fiscal year

Leave A Comment