Born in Papung VDC-5 of Taplejung district—where most people of the Dhokpya indigenous community such as him live—Sherpa drove a taxi in Kathmandu, on a contract, for about a year in and around 1997. He did it to raise his five children, although one can only do so much on a cab driver’s earnings. “I was required to pay the taxi owner Rs 17,000 a month,” says the now 43-year-old Sherpa, who has a contagious, disarming smile.

To get the most mileage out of his taxi-driving stint, he drove at night—because that’s when passengers pay more.

But that’s also when the driving is most dangerous. “Drivers who drive at night usually catch naps in their taxis and wake up to a prospective passenger’s call,” he explains, as he starts talking about a particular night-time escapade. One night in Chhetrapati, Sherpa woke up in his taxi to a loud knocking; a youth, who said that his father was a deputy superintendent of police, was brandishing a knife and demanding two hundred rupees. The youth threatened to stab Sherpa if he didn’t comply.

“To pacify the youth, I told him that I knew his father, and offered to take him for a cab ride; I could see that he was under the influence of drugs. I drove him to Durbarmarg and handed him over to police,” says Sherpa.

Driving a taxi, amusing incidents and all, was not the only job that Sherpa has had in his checkered past.

Before he became a cab driver, Sherpa worked as a “manager” at the Tashi Carpet Factory, in Bouddha. “My wife wove carpets in that same factory,” says Sherpa.

Later, Sherpa started his own factory—he started with two handlooms, his business grew, and he was at one time operating 17 handlooms, providing employment to 150 people.

“But that business failed, and I had to sell off everything, including my wife’s ornaments, to clear debts,” he says.

He had to start from scratch again, and that was when he turned to taxi driving, a profession that he later gave up in 1999, to join Rover Trek and Expedition as an assistant guide.

“As an assistant guide, my job was to accompany trekkers up to the base camp, and if they fell ill, I had to carry them piggyback. I also had to erect their tents and prepare their beds,” he says. During those years, Sherpa trekked to the base camps of several mountains, including Annapurna, Langtang and Kanchanjunga.

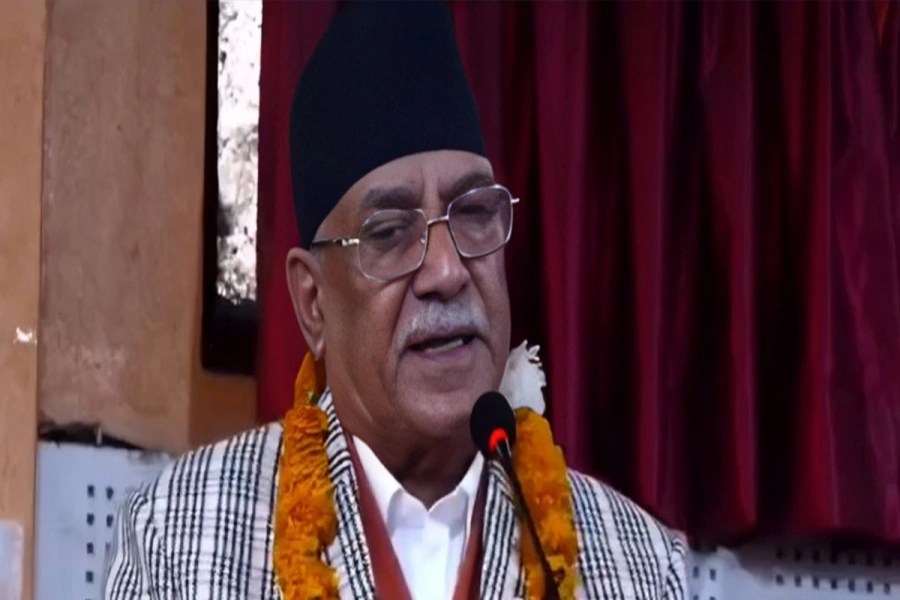

But Sherpa had undertaken all these ventures because he had been obliged to, to make ends meet. His heart lay elsewhere: since his youth, Sherpa had had a penchant for left politics. That is why, in 2000, he joined the Taplejung-Kathmandu Forum, a platform for left social workers. A year later, after the government recognized 57 groups as indigenous groups, including the Dhokpya, in 2001, Sherpa joined NEFIN as a Dhokpya representative. He became chairman of NEFIN two years ago.

Last year, Sherpa was nominated a member of the Constituent Assembly; he was among the 26 nominated by the cabinet, under recommendation by the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist). He had earlier refused the same post under the proportional system, citing the inadequate representation of indigenous nationalities in the assembly.

“I later accepted the nomination as I was encouraged by level of the representation for the indigenous nationalities among the 26 nominees. Also, friends at NEFIN said that I needed to go to the assembly even if all nationalities were not represented,” he says.

Today Sherpa travels in a 1400 cc Mahindra Logan, with a registration number of Ba.6.Cha 8849, for which he pays a monthly installment of Rs 31,000, a substantial upgrade from his green Maruti cab, with a registration number of Ba.A.Ja 3002.

It’s not that he’s become very rich.“I don’t have a house. I live in a rented apartment in Mahankal, Boudha,” he says.

Then what accounts for his splurging on the Mahindra before buying himself a house? Explaining his decision, he says, “I have always been a spendthrift. So investing in a car is my way of saving money, and the monthly installments are my savings,” he says.

That might sound like skewed logic, but in these times, especially when everyone is talking about the imminent housing-bubble burst, his investment choice seems pretty sound—a decision he might have made back in his entrepreneurial days: “When the assembly is dissolved and I no longer get the monthly salary from government, I will rent out the car. That will take care of my family’s upkeep,” he says.

bikash@myrepublica.com

Royal Trek being promoted during Visit Nepal Year 2020