Such forms of communication are crucial to the progress of any disciplined inquiry in the social sciences and humanities. In European history, prototypes of such journals have been brought into existence by the late 17th century. [break]

Some of the internationally influential journals that are still being published were established in the mid- and late-19th century in Europe and elsewhere.

‘What is an academic journal?’ Perhaps a broad definition would serve our purpose here: publications described as journals by its academic editors that appear in a series that can be numbered by volume (1, 2, etc.) or volume and issue combination (such as volume 1 no. 1 volume 1 no. 2, etc.) can be called journals.

Journals typically carry several articles by different individuals.

There is no standard format for how long an article ought to be but on average journals publish articles that are anywhere from 2,000 to 10,000 words.

Apart from main articles, journals also carry review articles, commentaries, book reviews and bibliographies.

Here is an account of some of the basic structural characteristics of the landscape of Nepali social sciences and humanities journals.

Numbers:

To my knowledge Nepal Sanskritik Parisad Patrika published in spring 1952 is the first academic journal to be published in Nepal. In the 59 years that have passed since then, at least 130 journals have been published.

Among them, three journals were established during the 1950s; six during the 1960s; seventeen during the 1970s; fourteen during the 1980s; 27 during the 1990s; and 63 since the year 2000.

The very first journal, Nepal Sanskritik Parisad Patrika, was published by an organization named Nepal Sanskritik Parisad.

The organization was founded in 1951 by some of the most influential writers, researchers and politicians of that time and its main objective, as mentioned in its constitution, was “the overall development of Nepali culture and to research on ancient subjects.

” The journal was edited by the polymath Isvar Baral. The second journal, Education Quarterly was founded in 1957 by the College of Education whose mandate was to train educators in Nepal. The third journal, Nepali, was published by a literary foundation, Madan Puruskar Guthi, in 1959.

Amongst the six journals that were founded during the 1960s, two (Purnima and Regmi Research Series) came from private collective and individual efforts, the former from the members of the Samsodhan Mandal gurukul founded by Nayaraj Pant and the latter from the pre-eminent economic historian, Mahesh Chandra Regmi; two came from Nepal Government bodies (Civil Service Journal of Nepal and Ancient Nepal) and one each from a university (Journal of Tribhuvan University which was later re-named Tribhuvan University Journal) and a professional organization of academics (The Himalayan Review published by the Nepal Geographical Society, NGS).

It is not very surprising to see that even though only a few journals had been founded in 1969, they were produced by a variety of institutional entities.

The political and civil freedoms that became available to Nepali citizens after the end of Rana-rule in 1951, the establishment of institutions of higher educational activities (such as the College of Education in 1956 and Tribhuvan University (TU) in 1959), and the establishment of professional academic bodies (such as the NGS in 1961) and research collectives contributed to the institutional diversity of academic locations from which journals were conceived, edited and published.

As Nepal government’s state apparatus grew in the immediate aftermath of the complete takeover of Nepali politics by King Mahendra in 1960, some state bodies also became editorial homes for a couple of journals.

In the 1970s, we see this pattern of growth achieving more density and outreach.

Among the seventeen journals published in that decade, some were published by extant institutional entities such as the central departments of various disciplines at TU.

Between 1975 and 1979 several such journals were launched: Voice of History (from history), The Economic Monthly (which was later re-named The Economic Journal of Nepal from economics), Geographical Journal of Nepal (from geography), The Nepalese Journal of Political Science (which was later re-named Journal of Political Science from political science) and Nepalese Culture (from the central department of Nepalese history, culture and archaeology).

Journals were also launched from TU’s new research centres.

These included the Contributions to Nepalese Studies from the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS), Education and Development and Vikasko nimti Siksa from the Centre for Educational Research Innovation and Development (CERID) and The Journal for Development and Administration from the Centre for Economic Development and Administration (CEDA).

Looking back, the 1970s seem to be a decade during which the central departments of TU and its research centres announced their coming of age with the publication of their journals.

New journals were also launched from governmental and semi-governmental bodies. Nepalese Economic Journal (from the central bank of the Nepal Government) and Pragya (from the semi-governmental Royal Nepal Academy) were some of the examples. Moreover, during this decade we also saw the establishment of a unique (for Nepal) working partnership between a group of academics and a commercial publishing house in the form of the journal Kailash.

This journal was editorially prepared by a group of academics, some independent, and others associated with various institutions.

The founding editor was late Hallvard K. Kuloy, a Norwegian who loved the Himalayas. He was assisted by a group of Nepali and non-Nepali academics with research interests in Nepal and the Himalayan region in general. This journal was published by Nepal’s leading commercial publisher, Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

At the end of the 1970s, a TU campus located outside of Kathmandu published a journal. Mahendra Ratna Multiple Campus Journal was published by the eponymous campus in Ilam.

After the end of the autocratic Panchayat regime and the beginning of a multi-party political dispensation in 1990, 90 new journals have been established.

Among them 27 journals were founded in the 1990s and 63 since the year 2000. The 1990s must be noted as the decade when journal publications were taken up seriously in cities outside of the Kathmandu Valley.

New journals were established in Pokhara (Historia and Journal of Political Science), Biratnagar (Vishleshan), and Ilam (Anweshana), among other cities.

Other journals were established by academic NGOs (e.g., Studies in Nepali History and Society), professional academic organizations (e.g., Nepal Population Journal, Nepali Political Science and Politics), government bodies (Janajati) and students (Discourse).

Since the year 2000, more journals have been established by various institutional entities. It is worthy of note that more new journals were established by institutions located outside of Kathmandu such as in Pokhara (three new journals) Biratnagar (three new journals), Baglung, Bhadrapur, Dharan, Surkhet (one journal each), etc.

In terms of the number of journals established outside of the Kathmandu Valley, this decade has surpassed the record of any previous decade. Independent organizations of academics also established new journals (e.g., Nepali Journal of Contemporary Studies, Journal of Forest and Livelihood, Shodhmala, etc).

In the second half of the decade (2005-2009), at least 30 new journals were established, which is a record for any five-year period in Nepali history.

It is also important to note that the total number of new journals (63) established since the year 2000 almost equals the number of journals established in the preceding five decades.

Institutional and physical geography:

Many journals in Nepal have been published by various entities associated with TU. For instance, TU’s research centres, central departments, other departments of its constituent campuses, its teachers’ association and its students publish journals.

Such journals are also published by other universities of Nepal (Kathmandu University, Nepal Sanskrit University), associations of specific-discipline oriented academics, government bodies, and semi-governmental bodies established by various acts (e.g., Nepal Academy).

They are also published by academic NGOs, private research centres, commercial publishers and political solidarities.

Given the concentration of institutions of higher learning and research and related practitioners in the Kathmandu Valley, it is not surprising to find that most academic journals are published from that location.

In terms of the rest of the country, Biratnagar and Pokhara produce a few journals each.

Such journals are also produced from Ilam Bazaar, Bhadrapur (Jhapa), Dharan, Bharatpur (Chitwan), Baglung, Nepalgunj, and Surkhet.

Given the tendency to start MA-level programs in different disciplines in parts of the country where they don’t currently exist, it will be safe to assume that academic journals will be, in the future, published in other new locations.

This tendency will be further boosted by the current preparations to establish new universities in mid- and far-western regions of Nepal.

Additionally, when the existing three universities (Purbanchal, Pokhara and Lumbini Universities) that currently don’t produce social science and humanities journals begin to do so, they will add to the institutional and physical diversity of the journal landscape in Nepal.

Furthermore, given the federal-bent of the Nepali polity in the future, it is to be expected that journal production will be physically more dispersed in the decade ahead than has been the case thus far.

Disciplinary focus:

Many journals do not have a disciplinary focus or emphasis but some do. For instance, a number of journals are published with the following disciplinary focus: history, geography, economics, political science, sociology and anthropology, culture, literature, linguistics, and demography.

These tend to be journals published by specific discipline-based departments at TU’s central campus or its constituent campuses or associations of academics of a specific discipline.

Considering the involvement of students in the production of at least three journals (Discourse, Samaj and Journal of SASS) and the fact that faculty-run journals are produced from Kathmandu, Pokhara and Baglung, the case of sociology and anthropology journals is probably the most interesting from the point of view of disciplinary dispersion.

Some other journals are multidisciplinary in nature by choice or by the circumstances of their publication. In the former category fall currently published journals such as Contributions to Nepalese Studies and Nepali Journal of Contemporary Studies.

These journals have published articles from a variety of disciplines in the social sciences and the humanities on various topics.

In the same category are other journals which are theme-focused, for instance, on education, folklore and media. With respect to journals that are multidisciplinary because of the circumstance of their publication, they are mostly journals published by an institution without being located in specific departments (e.g., Tribhuvan University Journal, Adhyayan: Mechi Multiple Campus Journal, etc.).

Also in the latter category are journals produced by various campus units of Nepal Teachers’ Association (Anweshana, Jana Pragyamanch, etc.).

Both of these types of journals tend to have a variety of topics such as social science, humanities and basic science writings since submissions from all academic staff across faculties present in the campus need to be entertained by the editors. This ‘mixed bag’ tradition has continued since the 1960s.

Language of contents

The working language of many nationally significant academics in Nepal continues to be Nepali. On the other hand, the number of social scientists for whom English is the working language is growing by the day.

Hence, the primary languages of publication of journals in Nepal, not surprisingly, are Nepali and English. Many journals print articles in both languages and are, therefore, bi-lingual (e.g., Ancient Nepal, Voice of History, etc.).

Some publish articles only in Nepali (e.g., Purnima, Pragya, Bangmaya, Media Adhyayan, etc) and others publish articles only in English (e.g., The Himalayan Review).

There is at least one journal that only publishes its contents in Nepalbhasa (Newari), namely, Nepalbhasa, published by the Central Department of Nepalbhasa of TU. Several journals are trilingual.

For instance, two journals, Ritambhara and Samakalin Matribhumi publish articles in Nepali, English and Sanskrit. Limbuwan Journal has published contents in Limbu, Nepali and English.

(This is derived from a longer article published in Studies in Nepali History and Society Volume 15 no 2)

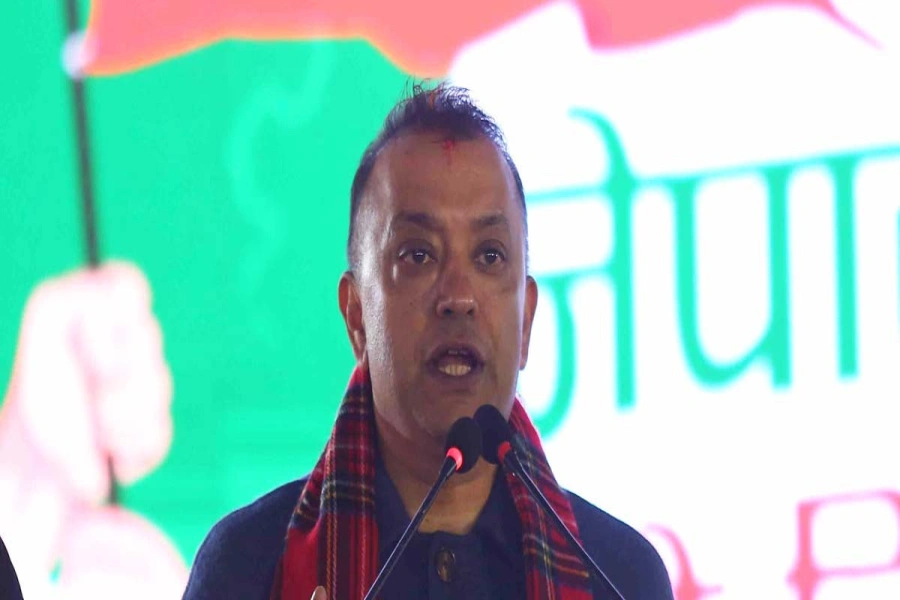

CPN-UML to look for ‘structural ways’ to implement 10-point agr...