OR

More from Author

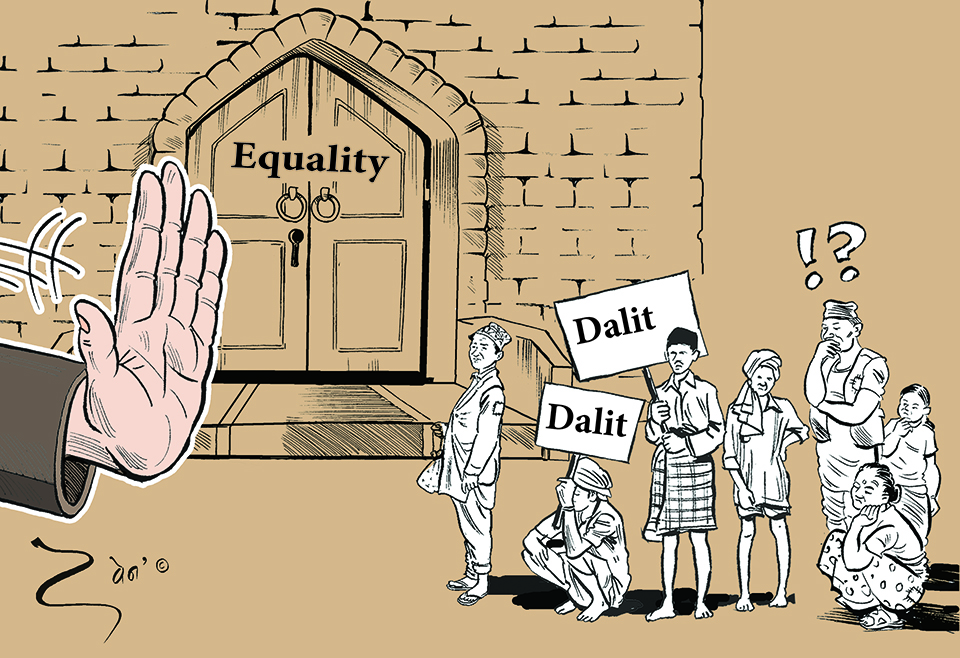

How many Dalits possess land in cities? How many Dalit students are enrolled in top-notch private schools and colleges? How many Dalit politicians are there in higher ranks?

Imagine this. There is a wedding reception in your neighborhood. You are invited like everyone else from your area. Once you get to the ceremony you are asked to stay away from the main area. You are served food separately.

You go to visit a temple near your home. While everyone is allowed to enter the temple to worship, you are asked to do so remotely from outside. Or you want to have a cup of tea and go to a tea house in your neighborhood. You are served tea outside of the shop. While the teahouse owner washes the used glasses of other customers, you are asked to wash it even when you pay the full price of tea.

Surely, we do not want to be in such situations. Sadly, Dalits who represent over four million people in Nepal face such situations every day. For generations, they have been facing far worse situations than in the aforementioned scenarios. They are the victims of the caste division which was introduced centuries ago and persisted in different ways and forms. The untouchability is still deeply entrenched in our values and behaviors, though it was outlawed decades ago in 1962.

Persisting problems

It is shameful that when the world is talking about missions to Mars and fully automated cars, a large share of our population still believes that they belong to “higher castes”. This thinking has created an artificial division of high castes and low castes, who are labeled as impure and forbidden entry to public places such as temples and ceremonies. Ironically, despite helping to introduce and sustain this inhuman practice, the “higher castes” consider themselves being more aware of human and social values and they consider it their responsibility to safeguard culture and tradition.

What is worrisome is people are discriminated based on their caste though caste system was abolished more than 55 years ago and Caste-based Discrimination and Untouchability (Offence and Punishment) Act was enacted in 2011. This not only made discrimination illegal, but also a number of programs to raise awareness were launched and a series of political revolutions promised equal treatment to all citizens. However, they delivered too little.

Daily news of people being tortured for entering temples and schools and marrying “higher caste” serve as the evidence, while most instances of discrimination go unreported.

The caste-based discrimination is considered normal in our society and sufferings of the victims do not touch us much. What seem to concern us is increasing rate of conversion among this group and the quota allocated to them in civil service.

We are not much worried about the structural discrimination they faced over generations. We do not seem to be bothered about an entire group of people lagging behind in almost every human development indicator. But the numbers relating to their conditions speak volumes. They have 41 percent poverty rate (national average is 25.16), 54 percent illiteracy rate (national average is 34), 50.8 years of life expectancy (national average is 59), 23 percent of Dalit being landless (their share in population is around 13 percent) with nearly half of them having less than two ropani land and the lowest (0.424) human development index (national average is 0.509).

Despite preserving arts and skills that we are proud of—such as our traditional musical instruments, folk songs, traditional metal craftsmanship, among others—Dalits suffer from discrimination and disadvantages across all spheres—social, cultural, political, economic, educational, health and religion. We enjoy their arts and express pride in what they produce and conserve, but we have directly or indirectly used the same to discriminate them, affecting every aspect of their lives—livelihood, educational opportunities and attainments, social and political inclusion to name a few.

While most of us consider ourselves progressive, we have not spared a minute to contemplate questions related to improving their situation and complete eradication of this inhuman practice. Instead, in social media, many of us shamelessly express our worry about the increasing rate of conversion. Why would they be interested to stick to Hinduism when the same religion is used to discriminate them?

Think about it

Let’s step into their shoes, and we will know why they need support from the state in accessing job opportunities. We will then realize that what the state is doing is far less from being enough suggesting the mere allocation of quota in the job is not enough. They need strong support in every dimension of their development until the playing field is leveled.

Let’s stop talking about culture or religion when discussing Dalit issues. Sati was also a tradition, but none of us want your mother to follow it when our father dies. If the tradition and culture are not just, we do not need to follow them.

Our generation no longer can afford to be silent if our tradition and culture discriminate against another human being. Caste-based discrimination is against law, humanity, morality, ethics and principles, and therefore needs to be uprooted.

You might be thinking why you should be worried when affirmative actions are being launched to increase their access to education and employment. But then how many Dalits possess significant amount of land in cities? How many Dalit students are enrolled in the top-notch private schools and colleges? How many Dalit politicians are there in higher positions? Are there any Dalit CEOs in any commercial banks or corporate houses?

Laws provide an important tool to support human rights of Dalits but they are not enough. The reports of the legislators, the executor and the judiciaries mediating for the settlement of cases of discrimination when it is illegal and or at worst harassing show how legal measures alone do not help. It is for those reasons most of their sufferings are suppressed in silence. Many crimes go unreported due to fear of reprisal, intimidation and inability to follow our costly and complex procedures to access justice. That means state support is not enough. There is urgency of actions from the citizens’ level.

We can no longer afford to tolerate discriminations and inequality. While those marginalized suffer the most, discrimination has its political, social and economic costs. Optimal development takes place only in an inclusive society. Thus we need to lift Dalits out of their segregated and discriminated status. Change is inevitable when we work together.

A movement—in whatever form—is needed to create a just society and those who enjoy more power and access to resources have the responsibility to launch such a movement. We need to advocate for stronger state support for the holistic development of Dalits. Our inactions mean we are allowing this inhuman practice to continue.

The author is an advocate of civil actions for social change

sangchalise@gmail.com

You May Like This

Mixed economic bag in 2019

Good news at the start of 2019 is that the risk of an outright global recession is low. The bad... Read More...

Economic case for road safety

If Nepal doesn’t act to reduce road injuries it might lose seven percent of GDP growth in the next two... Read More...

Tapping diaspora’s knowledge

Nepal should take a leap in scientific pursuit through mobilization of its large contingent of diaspora talent and scholarship ... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment