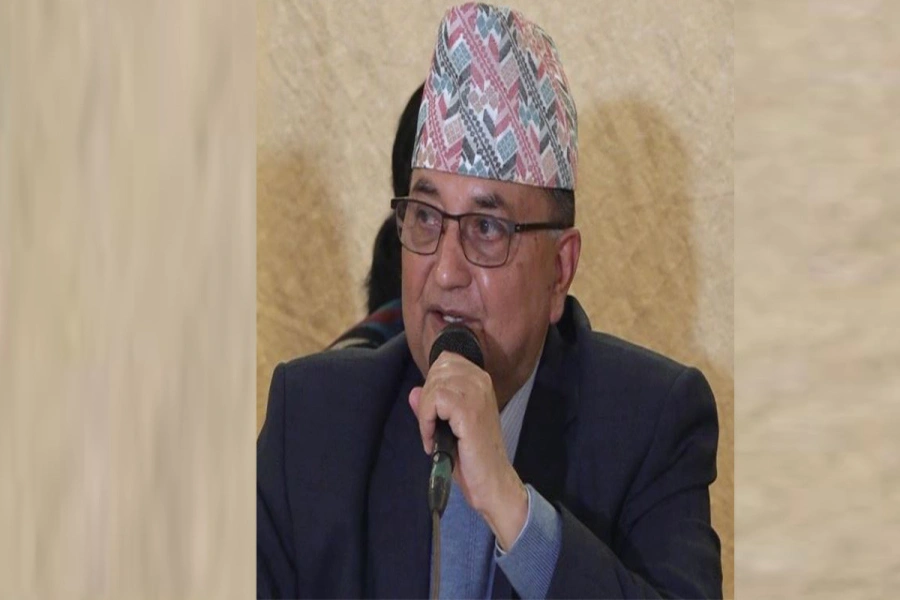

Newly appointed chief secretary Lailamani Poudel is known as a ‘reform-savvy’ bureaucrat within the civil service of Nepal. Soon after his appointment, he formed nine task-forces headed by secretaries to recommend ways of improving various aspects of our public service delivery. The reform buck, however, should not stop here. There are several other long-awaited bureaucratic reforms that need urgent focus.

Accountability is the crux of an effective civil service. Failure to institutionalize an external accountability culture within the civil service in the past has resulted in citizen-unfriendliness. An internal evaluation criterion at the discretion of senior civil servants to assess their subordinates’ performance for future promotions is a key factor responsible for the current unaccountability of the bureaucracy toward the citizens. This practice has increased ‘internal accountability’ because of which civil servants are more hakim-friendly and more involved in appeasing their seniors. Thus, the development of a mechanism for citizen participation in evaluating the performance of civil servants will enhance external accountability among our bureaucrats, a must for a thriving and robust bureaucracy.

In order to promote external accountability by reducing the civil servants’ internal appeasement focus, the internal evaluation system should be made more transparent and the ‘adjusted performance assessment (APA)’ system should be introduced and encouraged. Under the APA, the internal performance record of civil servants will be verified with external evaluation records made by the service users.

As other tools, public hearings, citizen report card surveys and community score card methods can be used to increase the bureaucracy’s external accountability and foster more fruitful relations between the service users and the entire bureaucratic set-up. The imbalance between internal and external accountability in our bureaucracy is highly perceptible and greater ‘accountability’ of civil servants to their political affiliations has also eroded their professional integrity and autonomy.

Another major drawback in our civil service is the lack of a strong monitoring and evaluation mechanism. Our bureaucracy has an ‘input-based monitoring’ system, which is more concerned with whether civil servants come to office on time or not. What we don’t have is an ‘output-based monitoring’ system which focuses on their deliverables and productivity. Development of an output-based monitoring system within the bureaucracy warrants greater productivity, effectiveness and performance on the part of civil servants.

The Administrative Reforms Commission Report (ARC) of 1992 has also strongly recommended developing a ‘performance agreement’ system to enhance accountability and improve the output-based delivery of civil servants. But two decades since, and this is yet to be implemented.

A majority of new entrants view civil service as being a ‘secure’ and less challenging job than private sector jobs. This psyche is also responsible for the lethargic and inefficient performance of civil servants. Till our civil service transforms itself from this ‘job-oriented’ to ‘service-oriented’ culture, it would be extremely difficult to witness any drastic reforms in the prevailing bureaucratic attitude and our bureaucracy will continue to remain citizen-unfriendly.

Another negative aspect of our bureaucracy is that many of the offices that need to have direct contact with the public do not have well-equipped ‘front-line service desks’. These desks, which people visiting the office first tend to approach, are either neglected or placed in remote corners with no facilities. The reform should begin with refurbishing such front-line service desks. Our civil service failed to make any efforts to change and adapt according to people’s needs, and factors likes accessibility and citizen friendliness.

Further, senior bureaucrats rarely seem to have an empathetic attitude toward citizens. Some confine themselves to their cozy offices during work hours and barely supervise how their subordinates are serving the people. The system of ‘management by walking around’ can be a good start to help mangers gain first-hand experience of how public services are being delivered to citizens, identify administrative lacunae and recommend corrections accordingly.

Capacity building also pays a key role in enhancing the competence and efficiency of bureaucrats. Though the ‘basic adjustment training’ is being provided to all officer-level civil servants to familiarize them with the nature of work and responsibilities assigned to them, such trainings seems to have yielded no outcomes as the bureaucracy’s capacity to deliver services to the people has not remarkably improved. The modules of such trainings need to be reformulated with a focus on mannerisms and attitude while dealing with ‘customers’.

Apart from a few pre-service and in-service trainings, civil servants hardly get any training to build their knowledge, attitude and skills. The case of senior officials may be different as they often go abroad for trainings, workshops and seminars. However, they rarely seem to bring back any learning. The secretary and joint-secretaries of the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare last year topped the list of foreign visits. Had they implemented even a quarter of their learning back home, things would have been different. The staff being deployed at the front-line service desks, who are mostly non-gazetted officials, hardly get any opportunity to visit other countries to hone their capacities and skills.

A few government offices in the past and the Supreme Court have initiated the ‘service with a smile’ approach. This was a commendable initiative towards fostering a culture of citizen-friendliness but it seemed to have been dampened by the lack of training, logistics and commitment.

The painful reality in Nepal is that even after five ARC Reports since 1953, coupled with countless recommendations to improve effectiveness of the public administration, our bureaucracy has remained exactly where it was, except with perhaps a few cosmetic changes. The already existing commission reports establish a fact that there is no dearth of suggestions, innovative ideas and recommendations. Why, then, have we failed?

What was recommended in the last six decades was hardly ever put to practice. Some of the reports failed because they were highly rhetorical while others failed due to staggering political will. Constituting high-level commissions, task forces and producing hefty reports alone will do not help refurbish our bureaucratic system. What we need is strong commitment and motivation at the level of the government and political establishment to implement these recommendations in order to evolve a transparent, accountable, effective and citizen-friendly civil service in the new federal Nepal.

pbhattarai2001@gmail.com

Bureaucratic red tape a major obstacle to reconstruction

-1765804380.webp)