However, ´federalism´ and ´form of governance´ are not an isolated issue in the larger social and political discourse. Nor can any final analysis be drawn without looking into these issues from the larger social and political perspectives. Therefore, it becomes pertinent to view such contentious issues by reducing them to ´federalism´ and ´form of ´governance.´ But most of the ongoing debates view the issues from ´reductionist´ perspective thus failing to provide ´holistic’ approach to the debate. This article, albeit with some limitations, will attempt to fill in those gaps.

Federalism and form of governance debate runs in the premises of ‘force’ or ´legitimacy´. Advocates of new radical form of governance and ethnic federalism have argued that the state will lose its ´legitimacy´ if it fails to guarantee directly elected president and ethnic federalism in the new political set up. On the contrary, the advocates at the other end contend that the state will lose its monopoly over collective ´force´ if it is divided on ethnic lines and absolute power is vested in the president or prime minister. Both the arguments bear merits and flaws. The most important aspect of this debate, which is sadly missing, is how well ´force-legitimacy´ equilibrium is maintained while drafting a new vision for Nepal.

It is not hard to admit that Nepali state, to a large extent, has lost its legitimacy to govern its territory and exert its monopoly through force. This type of legitimacy has been contested by new social, ethnic rights-based movements that erupted in the past decade or two adding complexities to exercise of monopoly by force. The state apparatus has largely failed because of extreme reliance on the practices of Max Weber styled state, failing to understand that both the state and society in Nepal have developed on principle of mutual interdependency.

In our times, top-down exercise of authority is no longer acceptable to Nepal as it has clearly spelt out its demands for rights, inclusion and self-determination to take charge of its own destiny. Nevertheless, political elites, who are not limited to Bahun-Chettris clusters alone, need to understand that state function requires a major re-dressing in order to regain its lost legitimacy. The longer they take to realize this, larger the chances for the state to remain fragile will be.

State has responsibility to ensure service delivery to its citizens that includes not only socio-economic goods, but also political participation and freedom at all levels. Merely setting up liberal democratic institutions with presidential or prime ministerial form of governance, judiciary and federalism—whatever the type—will not be enough.

In Authoritarianism´s Last Line of Defense, Andreas Schedler argues: "The new electoral authoritarian regimes of the post–Cold War era have set up the full panoply of liberal-democratic institutions—from constitutions to constitutional courts, from legislatures to agencies of accountability, from judicial systems to federal arrangements, from independent media to civic associations. Most important of all, they hold regular multiparty elections at all levels of state power.

In their institutional forms, these regimes are virtually indistinguishable from liberal democracies. Yet authoritarian rulers invariably compensate for these formal concessions with substantive controls. While renouncing the suppression of representative institutions, electoral authoritarian regimes specialize in their manipulation." If Nepali state is to retain its legitimacy, it has to rise above such manipulations.

n the other end of the spectrum; there are those who harp on the premise of inclusion and agradhikar, prior-rights, for legitimacy. The notion of inclusion, demand for a particular form of governance, federalism, and prior rights for caste and ethnicity, stems from their ´self-assumed emancipating responsibility´ towards the downtrodden. This logic makes mockery of its own precept for it is based on the principle of exclusion of ´others´. Therefore, the supporters of this notion are panicked by any alternative recipes that come from “traditionalists.” For them, the past is a disease to be eradicated once and for all because it is guided by false history and because it is opposed to modernity, freedom and progressive changes.

However, past has its own merits. In fact, it is only through past that modernity makes its route to promising future. In addition, the term modern is itself an outcome of tradition that has its root in the 5th century. In “Modernity versus Post-modernity” Jurgen Habermas argues: "The term modern has a long history, one which has been… used for the first time in the late 5th century in order to distinguish the present. . . With varying content, the term ´modern´ again and again expresses the consciousness of an epoch that relates itself to the past of antiquity, in order to view itself as the result of a transition from the old to the new." Therefore ‘new’ cannot be built by dismantling the old. The present draws its legitimacy from the past. The past will not simply vanish just because someone hates everything about it. It is here to stay and guide both present and future.

Another school of thought here has it that the issues of federalism and governance do not really matter as long as there is positive ´political culture.´ True. But culture alone does not build system. The proliferating discourse on form of governance and type of federalism seems to have a serious flaw—the outright rejection of alterative perspectives. But as the interdependence between state and society is the fundamental feature of Nepali society, the same principle should guide our ideologies too.

Coexistence of ideas, balance between force and legitimacy and determination to live together in spite of differences could potentially lead us to progressive future. But having read a few opinion pieces last couple of weeks in Nepali national dailies, I get the feeling that Nepali intellectuals have tended to ´shoot at the messenger´ instead of shooting at the message. This needs correction.

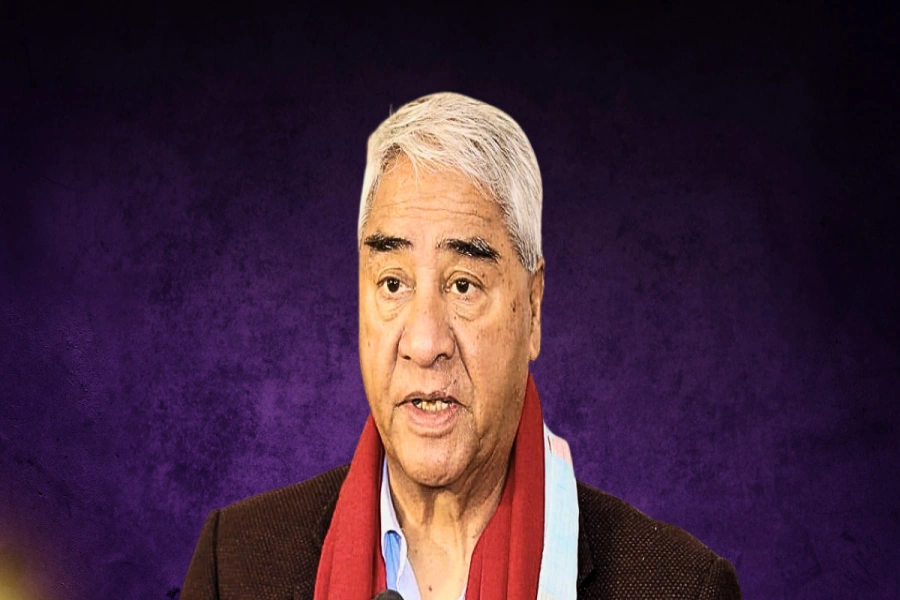

The writer is the author of Unfinished Journey: The Story of a Nation

sharmasumit77@gmail.com

From math to mud: How pottery became Mark Nafziger’s true calli...