OR

Dr Mahesh K Maskey

The author, former Ambassador of Nepal to China, is also a former Vice President of International Physicians for Prevention of Nuclear Warnews@myrepublica.com

Workers were not denying profit to the industry. They were demanding only a fair share of the value created by their own labor

In between the morning sips of my favorite cup of tea, I could not help wry smiles as I listened to the song Aljhechha Kyare Pacchyauri Timro Chiya ko Buta maa (perhaps your shawl is caught in the tea bush), in the backdrop of beautiful tea gardens and maidens picking up the tea leaves in my television screen. The cocktail of romance and melancholy of Bhupi Serchan and Narayan Gopal in this song has intoxicated a generation of Nepali listeners, myself included. But, oblivious to our inebriated eyes, generations of Nepali laborers were also enduring an ugly history created all along inside these beautiful tea estates by the unceasing contradictions of wage, labor and profit. Oblivious of the fact that along with the tea leaves, every day, the labor of young and old and male and female is churned and sucked in, to produce the tea for the market, profit for the owners and a bare minimum subsistence for workers.

Workers’ ordeals

Every day the workers had to turn themselves into a kind of automatons to pick at least 30 kilos of tea leaves in one shift, and repeat the routine throughout the season in lowest possible wage. Alienated from their own labors and trapped in a vicious cycle of work for survival and survival for work, there is no count of their prematurely aborted dreams that have been flushed away with their non-stopping sweats. They did try to tell their story in the past, through demands and agitations for wage raise and equal wage for male and female workers. But like bubbles bursting before they could register their existence, their struggle kept on disappearing before it could penetrate nation’s consciousness.

But this time it was different. The tea workers came to the streets with a resolve to fight and win. They had calculated well and seized the opportunity. It was the minimum wage set by Labor Regulation (2018) which the new government led by Nepal Communist Party has granted them. The workers simply told the estate owners and the government to execute the provision, no more, no less. They descended from all places to block the road in Birtamod, lying on sweltering coal tar topped street to draw the nation’s attention to their plight. Some of them were starving, resorting to roots and tubers for survival because they could not afford to buy food for themselves and their children. The government, which was supposed to execute its own labor regulation, appeared helpless or reluctant, adding suspicion that the regulation was only a populist document at best, a paper tiger with teeth of cotton.

Delay is always an immensely effective tool to break strikes. The tea estate owners warned that the industry will collapse if government complies with workers’ demands, simply because the profit from industry cannot sustain the expenses of labor cost. After weeks of vacillation, the government stood firm. It took 45 days to fulfill workers’ demands, but they returned to work with their heads held high. There victory however is bound to reduce the profit of the owners, so what if the tea industry really collapses? If the factories shut down workers’ jobs will also disappear. Were the workers, like the proverbial Kalidas, cutting the same branch they were sitting on, strangulating the industry to deny profit for its survival? Or were the workers demanding only a deserving share of the value created by their own labor which was being expropriated by the owners as their profit? Therefore, the tea workers’ movement has once again raised the classic questions: What is profit? What is the role of wage laborers in creating profit? These questions make us revisit Karl Marx and Adam Smith.

Lens of Marx and Adam smith

As and when we start pondering over this question, the image of Karl Marx appears like a specter. Before him, particularly in view of Adam Smith, profit was thought to be an outcome of circulating capital (money and raw materials) and products. The fixed capital (machines, buildings etc) can increase the productivity of labor but cannot produce anything without circulating capital, he opined. One has to take risk for the investment of this capital, and therefore, Smith believed that capitalists and landowners should be rewarded for their entrepreneurship.

For a long time this argument was treated like a gospel. It was the time of rise of capitalism in the world stage. But to be fair to Adam Smith, he also said that labor is the real measure of value imparted to a product and hence it should be rewarded. Such proposition was a defining moment for the labor theory of value which is actually credited to John Locke who, a century before Smith said “what is taken from the earth through labor rightfully becomes the property of the laborer. Cultivated land is more valuable than fallow land as a result of labor.” He also extended this concept to all manufactured products.

Marx was to refute the propositions of Adam Smith by exposing the contradictions inherent in his argument. “Smith’s conclusion that capital is the source of profit contradicts with his passage that command of labor is the source of value,” Marx said, and then tabled his most powerful explanation of what makes profit: “If labor is the source of value then the profit must originate from the differential between what the laborer is paid and the value the laborer has produced.” That is, of all the total value a laborer creates by selling her labor-power (eight hours working shift or plucking 30 kilos of tea leaves in one shift for instance), she receives only a part of it as her wage and the owner keeps the rest as his profit. This portion of value which is taken away is the “surplus value” created by the laborer, which the capitalist calls ‘profit.’ This is the essence of the Marxian theory of surplus value. From this standpoint, the entrepreneurs look more like gentlemen stealing the value generated by laborers and pocketing the profit, if such surplus is not primarily reinvested for social welfare.

Marx has been vilified (and lionized) for more than a century and a half for this proposition. At times many people thought he may have committed a blunder. The source of profit, they said, is capital, demand and supply, circulation of commodities, invisible hand of market etc. But he stood the test of time remarkably well, being voted as the millennium’s greatest thinker in BBC poll. At present, many new cuts from the surplus value, not imagined by Marx, will go out of the capitalist’s pocket such as various taxes, donations to parties and social groups, not to talk of underhand bribery. However they are also, in the final analysis, part of labor-created surplus value.

Rescuing Smith and David Ricardo from the limitation of their labor theory of value by introducing the concept of ‘labor-power’ as the ‘exchange-value,’ Marx stands tall as the symbol and advocate of primacy of labor. Alarming rise of global inequality in wealth has substantiated his predictions. His view about what makes profit and endangers inequality at the same time has not been superseded. On the other hand, the rising discontent within the theory and practice of capitalism and the mounting struggles of workers and peasants in response to inequalities are also laying bare the deep-seated contradictions of capitalist world system. So much so that some thinkers like Nobel laureates Joseph Stieglitz and Paul Krugman are advocating for what is called Progressive Capitalism which sounds like an oxymoron but which they claim it is not. I think Nepal can draw a lesson or two from this supposedly new concept.

Back to the workers

As Nepal stands in a juncture of history where the neoliberal finance capitalism or globalization is sinking by its own weight, and where Nepali society is coming out of atypical mixture of pre-capitalist mode of productions, the option appears to be a transitional path between progressive capitalism and socialism: a variant of welfare capitalist state that strives for socialist goals, by consciously transforming its socio-economic relations for the growth of productive forces. In such transition, encouraged and supported by the state, the capitalists may want to transform themselves as social entrepreneurs where a substantial share of the surplus generated by the labor is spend in the welfare of the laborer as a conscious tribute to their contribution. The workers and farmers, on the other hand, manage productions by owning means of productions through their cooperatives, and enjoying their work rather than get alienated from it.

Having been through these thoughts in a flash, I could see that that workers were not denying profit to the industry, they were demanding only a share of value created by their own labor. The enlightened owners would someday understand this dynamics and voluntarily use their entrepreneurship to provide the laborers what is their due, while keeping fair share of the value produced by their own labor as well.

Amidst this brief lapse of a strange but gratifying thought process, the song was still playing on the screen. I found my wry smiles being replaced by the genuine ones. The joy appearing in the maiden’s face while plucking the tea leaves in my television screen does not appear to be fake now. And the sweet intoxication of the romance and melancholy of ‘Aljechha’ song is back along with the familiar aroma and taste of Ilam tea.

maskeymk8@gmail.com

You May Like This

Only five percent of tea farmers take loans to expand business: Report

KATHMANDU, July 14: Although tea has been considered as a competitive product of the country, most of the tea farmers... Read More...

PM, Speaker shun tea reception hosted by CJ Karki

KATHMANDU, May 9: The differences among Legislative, Executive and Judiciary were clearly visible on the Law Day following the impeachment... Read More...

DDC to sell packaged tea milk

KATHMANDU, July 15: Dairy Development Corporation (DDC) is launching packaged tea milk and from Saturday. ... Read More...

Just In

- Nepal faces Bangladesh Red in int'l U-19 Volleyball Championship final

- Nepal Investment Summit: Two organizations sign MoU for PPP cooperation

- Sita Air flight to Ramechhap returns to Kathmandu due to hydraulics issue

- Man found dead in Dhanusha

- Gold prices decreases by Rs 400 per tola

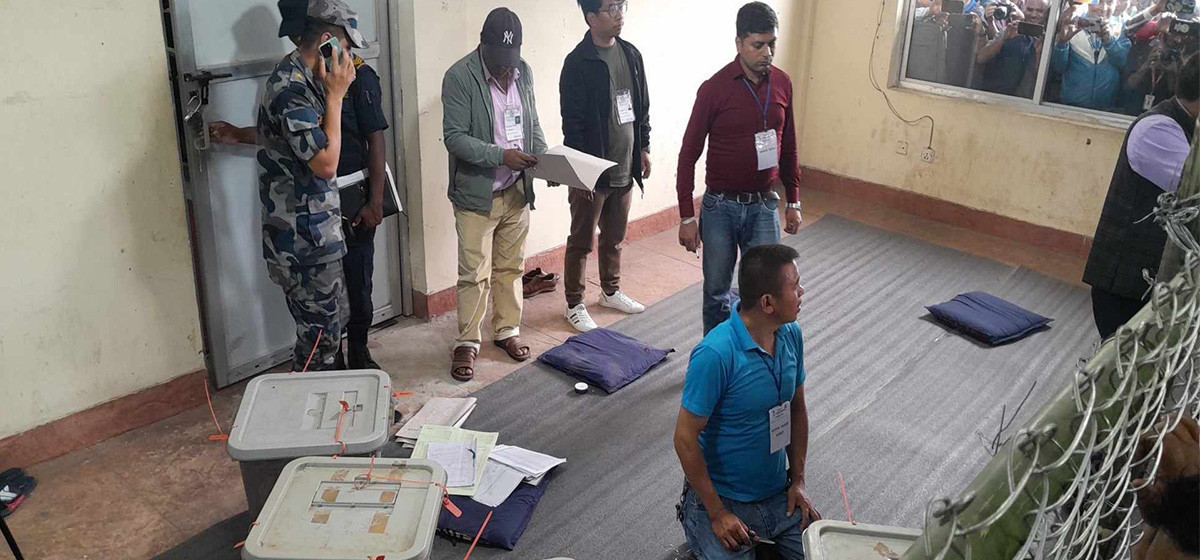

- Ilam-2 by-election: UML candidate Nembang secures over 11,000 votes

- High-voltage power supply causes damage to 60 houses

- Bajhang-1 by election: UML leads again

Leave A Comment