The main reason for low foreign investment in Nepal is not multinationals’ ignorance of opportunity but their full knowledge of unfriendly business environment in Nepal

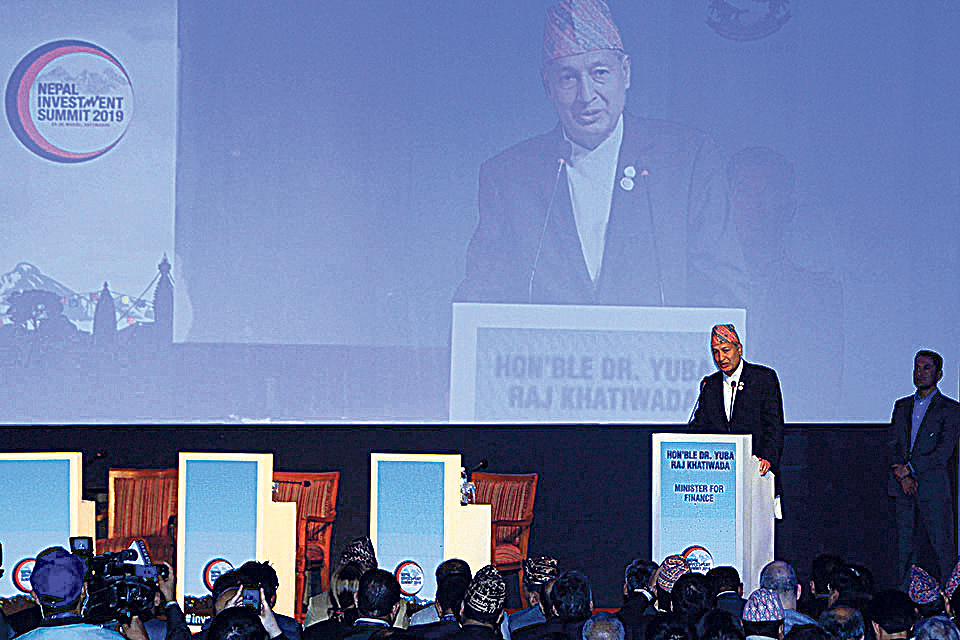

The government of Nepal has organized Nepal Investment Summit, only two years after holding a similar conference, with more than 600 delegates from foreign governments, multinational institutions and companies around the world. Government has showcased 77 projects with cost of US$ 33.6 billion, and the private sector has proposed 17 projects at $1.8 billion, making the conference price tag $36.4 billion. These projects, whose costs range from $1 million to $6.6 billion, are open to citizens for investment, but the intended target is foreign direct investment (FDI).

To put this in perspective, the total price tag is 184 times the amount of FDI that Nepal received in 2017 ($198 million), which was the largest annual flow in Nepal’s history. If the banner year’s performance continues, it would take 184 years to accrue that much FDI. To make it sound less astronomical, it is equal to the remittances that Nepal has received in the last seven years.

In any case, the motive here is not to judge the conference’s content but to assess whether and how Nepal can muster substantial FDI whose global supply is limited and whose flow is highly concentrated in few countries. For example, in 2017, out of global production of $80 trillion, FDI was only $1.4 trillion (1.8 percent). The top 20 recipient countries absorbed 80 percent of it, leaving 20 percent to all other countries in the world.

Report card

Nepal’s record in welcoming FDI is dismal. Even when adjusted for size, Nepal is the least favored country by foreign investors in South Asia. In the last five years, Nepal’s inward FDI was only 0.42 percent of its domestic production, with the next smallest fraction for Bhutan at 0.62 percent. By comparison, it was 1.2 percent for China and 1.8 percent for India.

In general, the smaller the country, the higher the share of inward FDI in domestic production. But Nepal has been an exception. Its neighbours, China and India, however, are the two most favored destinations. In 2017, China was the second largest recipient of FDI after the US, obtaining 9.5 percent of global FDI and India was the tenth largest recipient, capturing 2.8 percent.

Foreign investment commitments decrease by over Rs 21 billion

To be surrounded by such innovative economies with more than two billion population is arguably a blessing for an innovative nation. Nepal, however, has yet to realize it. But make no mistake. Nepal’s prosperity is impossible until Nepali companies compete and succeed in these markets. The FDI and massive amount of it would be a great launching pad for this triumph.

But competition cuts both ways in scarce resources like FDI. There is a danger that Nepal falls on the blind spot of its neighbours’ attractiveness. To avoid this risk, Nepal needs to have a convincing answer of the vexing question: Why would any company invest in Nepal if it can do so in China and India and serve Nepal from there? Country-specific endowed sectors such as hydro, tourism and other non-traded service sectors may escape this scrutiny but other sectors cannot.

This question arises because Nepal is not only very small it is also less developed with a lack of physical infrastructure (transport and energy). Compounding the problem, Nepal is more expensive for conducting business than China and India. Based on the rankings in four indices—ease of doing business, cost of start-up, corruption perceptions and global competitiveness—doing business in Nepal is 23 percent more expensive than in China and 15 percent more expensive than in India. Adding to this are the disadvantages incurred due to landlocked nature, unskilled labour, sub-par education and not-so-developed companies. Combined, Nepal has huge hurdles to clear to make it a FDI-host rather than a supply market.

Though the barriers seem to be natural and policy-induced, it is the latter that is causing the damage to the point of aggravating even the former. To pinpoint, the main obstacle is the lack of business-friendly environment—ease in doing business, clear tax treatment, transparent rules, good governance, adherence to rule of law. In fact, the main reason for low foreign investment in Nepal is not multinationals’ ignorance of opportunity but their full knowledge of unfriendly business environment in Nepal.

Course of action

The only way to surmount this challenge and make Nepal a desired destination for FDI is by showcasing Nepal as one of the most-business-friendly countries of the world. Achieving this milestone is difficult, but not impossible. For this to happen, deep-rooted policy changes, some of them outlined below, are required.

First, one-window solution. We have been hearing this since Panchayat era but with no action. Do act. Make it happen. Irrespective of investment size, assign one authority to examine, approve, and provide all necessary documentation, rather than the present arrangement of different ministries, boards and commissions. Same with domestic investors.

Second, ensure that Nepal ranks better than China and India in the ease-of-doing-business index within a year. Aim to make it one of the best globally, in the next three years.

Third, scrap all policies and regulations that discourage domestic investment. The best policy to promote FDI is the one that promote private domestic investment, the backbone of a country’s development. Vibrant domestic companies entice joint venture and partnership with foreign companies. Take it to heart: A smart FDI silo cannot emerge within an inefficient domestic investment regime. The latter is the trend setter.

Fourth, bring policy changes that reverse the present trend of national saving flowing to land, real estate, schools, and hospitals. Due to wrong tax, education and health policies, these sectors yield higher return to private investors. Why would we expect foreigners to invest in sectors that have lower return, when they have to incur the same labor and land costs?

Fifth, aside from sectors that are related to national security and small endogenous cottage industries, open all others for FDI. Clearly define in which sectors minority and majority ownership is allowed. In doing so, be mindful of the research finding across many countries that foreign-owned companies generate better economic outcomes than domestic-owned.

Sixth, whatever the investment incentive package the country can afford, make it uniform across all sectors without any sectoral bias, which has the danger of misallocating resources.

Seventh, make investment incentives size-neutral. A country requires business of all sizes. So encourage them uniformly.

Eighth, treat investment from all nationalities, including from Non-Resident Nepalis, with the same incentives. Investors are working at a low margin; a slight favour to one nationality will bar others from competing, imposing cost on Nepal. It’s a global world and Nepal should aspire for FDI globally.

Bottom line

The Investment Summit 2019 is a positive step in the right direction, but it only showcases Nepal’s need and does not have much to showcase on Nepal’s business-friendly score-card, which is multinationals’ needs.

We can expect that some funding will be secured for a few projects in hydro, tourism and of strategic importance from its neighbours. But to rally FDI in large scale, across all sectors and from around the world, as hoped by the organizers of the summit, Nepal has to be one of the best countries in the world to do business. Then only, with its beauty, tranquility, unique natural set up and pro-business attitude, Nepal can be a favored destination for FDI.

The author is an economist and is associated with University of Ottawa

acharya.ramc@gmail.com