Nepali music has come of age!

With that conviction, I finally reach a happy point while ending this “Fear and Loathing at Radio Nepal, 1966 – 1976” series, and I cannot conclude my essay without commenting on Nepal’s new national anthem – “Sayaun Thunga Phoolka Hami” (One Hundred Stems of Blooms that We Are).[break]

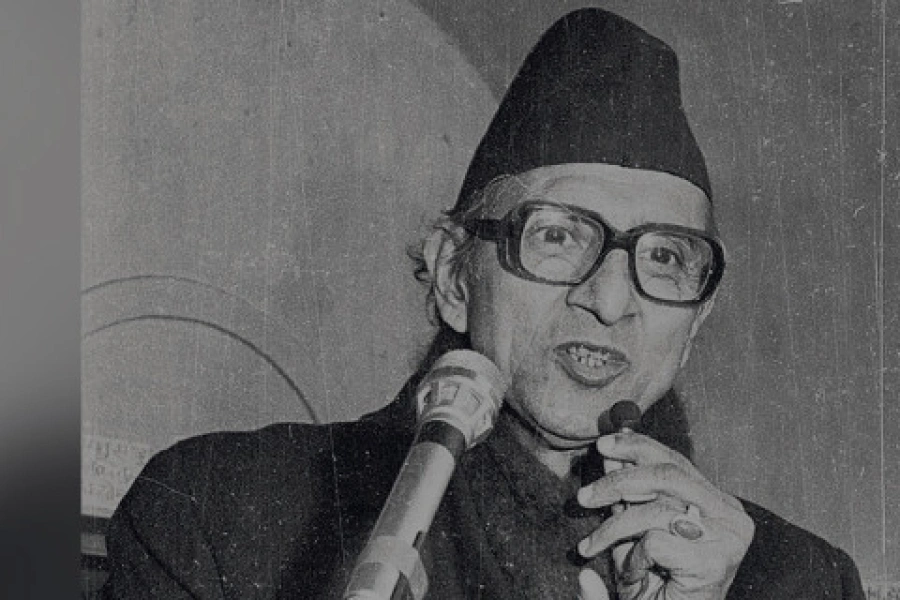

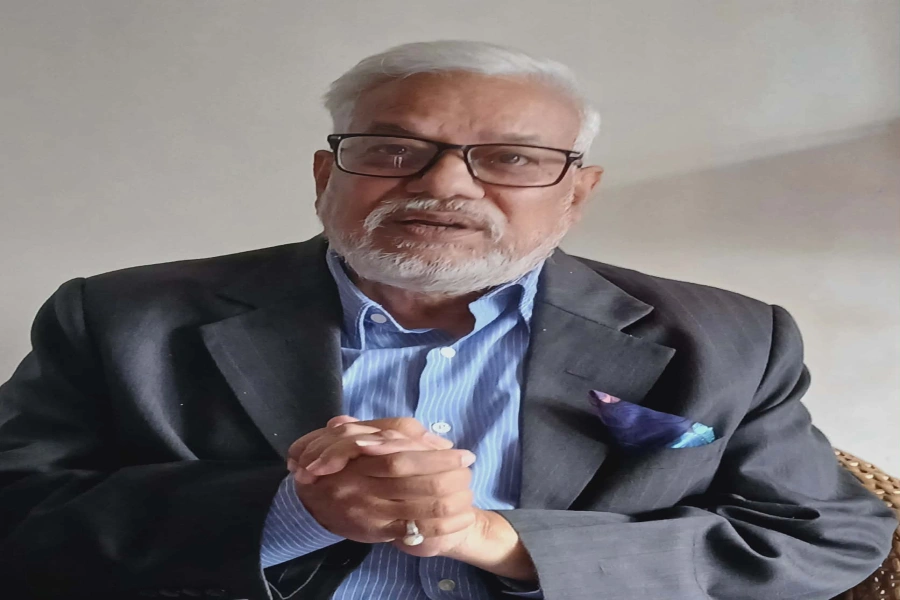

The lyrics, written by Pradeep Kumar Rai or “Byakul Maila” (Restless Second-Born Son) under the aegis of a national competition, are set to music by Amber Gurung, and this is the new signature song of Nepal as a Federal Democratic Republic since 2007.

As a distinctive national anthem should traditionally be, Nepal’s own is a one-minute entity, requiring it to paint a passionate portrait of the nation as completely as possible in words and music within a 60-second format.

A national anthem is an amalgam of a particular people’s collective literary and musical ardors, historical passions, nationalistic emotions, evolved evocations, accrued feelings and earned sentiments, and as artistically reflected and representatively crafted as possible, with the highest regards to their beloved country, and with due manifest aspirations of a nation-state. This is a people’s manifesto, declaration and address made by them to themselves on the live witness stand of their nation’s ample bosoms and spacious laps accommodating one and all. A national anthem is the eternal love letter of her loving children to their one and only Motherland.

Nepalis now have one such hymn of/by/for their own.

That being the general preamble to Nepal’s new anthem, there are a few particularities of the modern folk-based hosannah dedicated to her and her children, and these salient points have stricken me, and I wish to share them with readers.

The first pointer to attract my attention as a past and retired musician is the chordal makeup of the song. It is believed that “Sayaun Thunga” is in Gm (G Minor) and ends on Bb (B Flat) Major. While Bb and Gm are considered relative chords in western music, the beginning of the song itself in Gm, instead of the principal Bb, is intriguing – even in western musical canons. As a simple rule in musical composition, it is Gm that should follow the melodic line launched by Bb as the tonic base, and not vice versa. But that is exactly what has happened in Nepal’s new national anthem. Beginning a song on a minor chord strain (Gm) and finalizing it on a major note (Bb) is rather unique, even universally speaking. Therefore, music composer Amber Gurung has executed a coup in Nepal’s new identity song as a duality of poetic diction and tuneful music.

It is understandable if the canonic musical explanation I attempted above is all Esperanto to readers and those interested in the melodic construction pattern of the song. This is where a modern composer needs to stand on a platform, facing his curious and questioning audience, and demonstrate the architecture of his work – even if it is a mere 60-second song – by PowerPoint presentation, color-coded graphs, pie charts, stats and other visual aids superimposing the lyrical lines vis-à-vis the melodic progression of the song in question. Mere explanation in black-and-white words, as I tried to do above, won’t do complete justice. It is time the mathematics, physics and mechanics of modern music were laid bare before people who need to know fully well in order to appreciate the full force and impact of something like the new national anthem of their most dearly beloved country.

सयौ थुङ फूल क हामी यौतै मला नेपाली

सर्वभौम भए फैलिएक मेची महाकाली

प्रकृती क कोती कोती सम्पादकओ आचल

बिर हरुका रगता ले स्वतन्त्र र अतल

ज्ञान्भुमी शान्ति भुमी तरइ पहाद हिमाल्

अखन्द यो प्यारो हाम्रो मतृभुमी नेपाल्

बहु जाती भाषा धर्मा सन्स्कृती छन बिशल

अग्रगमी राष्ट्र हाम्रो जय जय नेपाल

Sayau thunga phool ka hami yautai mala nepali

Sarwabhaum bhae failiyeka mechi mahakali

Prakriti ka kotee kotee sampadako aachala

Bir harukaa ragata le swatantra ra atala

Gyanbhumi shanti bhumi tarai pahaad himal

Akhanda yo pyaro hamro matribhumi Nepal

Bahu jaati bhasha dharma sanskriti chhan bishala

Agragami rastra hamro jaya jaya Nepal

From one sensory angle at least, it is not difficult to see why the composer did what he did. A minor note (“swor’) in Indian classical music is called “komal” while a full/major note is “suddha.” Why Amber Gurung chose to launch the anthem in a minor chord and on minor notes is because “komal” also means “soft” – and the anthem’s very first line has the word “phool” which means flower. Certainly, the delicate duality of “soft” and “flower” had to receive a suitable poetic justice in Gurung’s notation. Thus a minor musical note has a major function to denote the “soft”-ness of the “komal” blossoms mentioned by lyricist Byakul Maila while idealizing the sovereign peoples of Nepal to one hundred species of blooms.

Additionally, if a minor note is taken negatively, as it universally is, a major note is symbolic of positivism; and the national anthem of Nepal should conclude on a positive note of hope, faith, and aspirations for the greatest good of the Nepali peoples and their proud nation.

Secondly, Nepali lyrics are distinct at least in one way: It is that words in Nepali songs are mostly endemic, indigenous, local, provincial and regional for national identity and resonance. Thus, popular Nepali verses are vernacular in sense, sensibility and structure, meaning that Nepali lyricism never allows Sanskrit intrusions, as it is in the case of other genres of Nepali literature, especially poetry. Rather, Pali is more welcome in Nepali songs than is Sanskrit, for obvious folklorist and popular/democratic reasons.

In this given, Amber Gurung recognized the folksy soul and spirit of Byakul Maila’s lyrics, and likewise he composed the anthem’s post-modern melodic lines on Nepali folk métier. Thus, it is an ideal marriage of Nepal’s pastoral and rural and the world’s contemporary harmony.

Thirdly, the rhythmic pace of the anthem is also intriguing to me. Call it beats or bars or whatever timing device, the cadences are of two mutually matching strides in the song. The composer says the anthem has a “jazz beat” of a steady 1-2-3-4/1-2-3-4 “swing” progression. The same beat, however, is also convertible to 6/8 (double of 3/4) beat, popularly known as “khyamta” in Indian classical music. The pace count is the same but the inner cadences can be adjusted to what Indian classical music defines as “manda” for moderately slow and “druta” for steadily fast beats, or “taal.”

This two-in-one form of rhythm-keeping is ideal for Nepal’s diverse populations living in varied topographies and terrains. It is worth suggesting, therefore, that people of the up-and-down-and-hardly-level higher hills may resort to the casual swinging jazz beats of the national anthem while the inhabitants of the valleys and Tarai and Madhesh may take up the robust version of the khyamta taal.

I further suggest that schoolteachers and students, who sing the national anthem during their morning assembly, may take note of the anthem’s characteristics as described above, and they may gain some inner knowledge of their new national anthem which is already five years old.

BBC evaluated the national anthems of the participating countries at the Beijing Olympics and placed Nepal’s national anthem in the top fifteen. This was a great honor for Nepal though the news got scant notice in Nepal’s media. The selection was made purely on melodic and rhythmic basis, and therefore, Byakul Maila’s “jharro” lyrics in folksy Nepali needs translation and worldwide dissemination.

As for Amber Gurung, it is a full musical circle that began with “Nau Lakh Tara Udae” in the 1960s and he has received the latest national laurel for the musical composition of “Sayaun Thunga Phoolka Hami.” And for writing the words of the anthem, Pradeep Kumar Rai, a.k,a, Byakul Maila, too, is Nepal’s honorary lyrics laureate for life.

Parting shot

Well, here I am! From a past practicing and performing guitarist, bassist, singer and occasional lyricist, I am here as a storyteller and reporter of things past and present. Having done my tasks, I may as well rest this series at this juncture and take my leave.

As I said somewhere above: It has been a lark – all along the way!

This final installment concludes the series.

Grateful acknowledgements:

This 27,000-word series published in 16 parts in The Week/Republica every Friday since June 29 would not have been possible without the support of the following:

• Mr. Arpan Shrestha, the Editor of The Week, who instigated me to write the series;

• Ms. Cilla Khatry – colleague, friend, guide, counselor and spoon-feeder at The Week – who supervised the serialization of this series;

• Mr. Sworup Nhasiju for delightful sketches; and

• Readers who read the series and wrote warmly and kindly to me.

I thank them all.

THE END

The writer is the copy chief at The Week and can be contacted at pjkarthak@gmail.com

Kathmandu Cantos