Billions of people around the globe are desperately trying to learn English—not simply for self-improvement, but as an economic necessity. It’s easy to take for granted being born in a country where people speak the lingua franca of global business, but for people in emerging economies such as China, Russia, and Brazil, where English is not the official language, good English is a critical tool, which people rightly believe will help them tap into new opportunities at home and abroad.

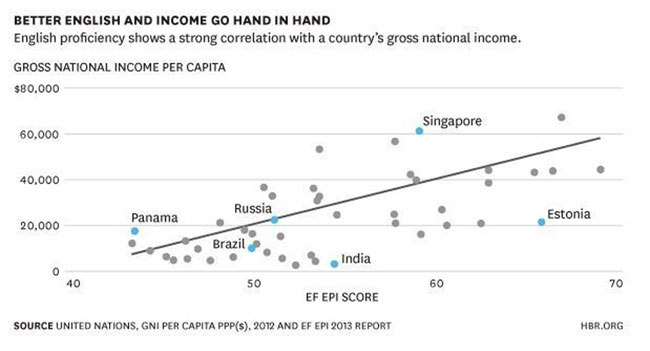

Research shows a direct correlation between the English skills of a population and the economic performance of the country. Indicators like gross national income (GNI) and GDP go up. In our latest edition of the EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI), the largest ranking of English skills by country, we found that in almost every one of the 60 countries and territories surveyed, a rise in English proficiency was connected with a rise in per capita income. And on an individual level, recruiters and HR managers around the world report that job seekers with exceptional English compared to their country’s level earned 30-50 percent higher salaries.

The interaction between English proficiency and gross national income per capita is a virtuous cycle, with improving English skills driving up salaries, which in turn give governments and individuals more money to invest in language training. On a micro level, improved English skills allow individuals to apply for better jobs and raise their standards of living.

This is one explanation for why Northern European countries are always out front in the EF EPI, with Sweden taking the top spot for the last two years. Given their small size and export-driven economies, the leaders of these nations understand that good English is a critical component of their continued economic success.

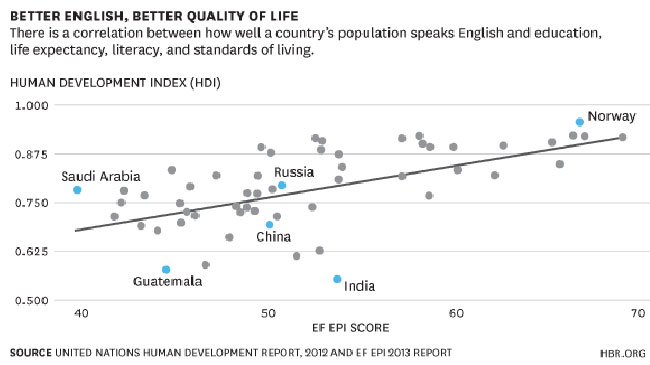

It’s not just income that improves either. So does the quality of life. We also found a correlation between English proficiency and the Human Development Index, a measure of education, life expectancy, literacy, and standards of living. As you can see in the chart, there is a cutoff mark for that correlation. Low and very low proficiency countries display variable levels of development. However, no country of moderate or higher proficiency falls below “Very High Human Development” on the HDI.

Source:World Economic Forum

Source:World Economic Forum

Teach them English