OR

Pramod Neupane

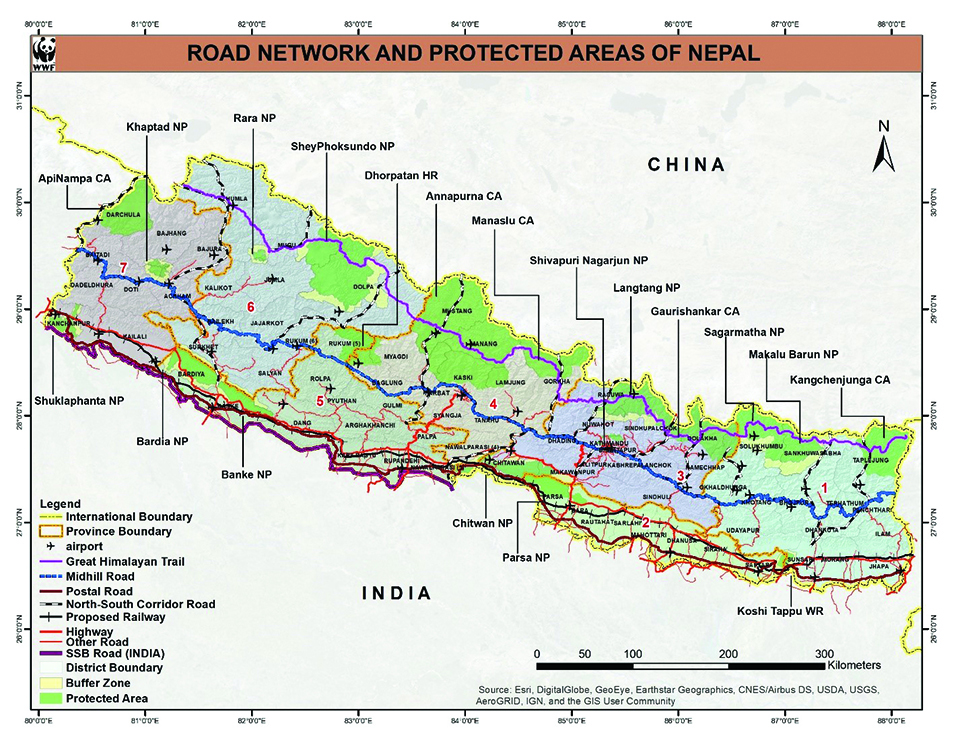

The author is the senior program officer of the infrastructure program at WWF Nepalnews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

In the absence of proper monitoring and precaution, highways that are being envisioned will most certainly increase Vehicle Wildlife Collisions

An adult male tiger was killed by a speeding bus in Bardiya National Park on December 21, 2016, the first ever wildlife roadkill incident that became a national issue. Likewise, a young leopard was hit by a Toyota Hiace on January 2, 2018 on the highway crossing in Banke National Park. This was one among the seven leopards killed in a road accident in Nepal in fiscal year 2017/18. To add to the list was the incident on January 11, 2019 where a tiger was knocked down by a speeding truck on the East-West road traversing through Bardia National Park. Thankfully, the incident didn’t kill the tiger but its struggle of recovery and returning home to the wild, lingers.

These are but only a few of the major incidents that have taken the life of the top and rare wild predators that determine the wellness of the overall ecosystem along with the wellbeing of other wild animals in the food chain pyramid. And, although Nepal in particular has been sensitive towards cases of unnatural wildlife deaths, human-wildlife conflict, illegal wildlife poaching and Vehicle Wildlife Collisions (VWC), many such incidents especially when it comes to prey bases including ungulates and macaque species fail to make headlines.

VWC accounts for most wildlife kill in Nepal. In fact, the wildlife kill data for the last fiscal year shows that roadkill contributed to 124 or 83 percent of total unnatural deaths of animals; a five percent decrease from the 133 (88 percent of total unnatural deaths) recorded in preceding fiscal year across the protected areas of Nepal.

Contrary to the conservation successes; be it achieving zero-poaching of rhinos five times or almost doubling tiger numbers, the challenge of viable sustenance of the increased population remains. Infrastructural development in Nepal is gaining momentum with the government’s motto of “Prosperous Nepal, Happy Nepali”. Four East-West Highways have been envisioned for Nepal. This includes the existing two-lane Mahendra Highway (1028 km) that is being extended to four lanes, Mid-hill (Pushpalal) Highway (1776 km) being explored to increase connectivity within the hills of Nepal and the Madan Bhandari Lok Marga (1225 km) envisioned to traverse the foothills of Churiya Ranges that is expected to increase connectivity therein. Additionally, the Postal Highway (1792 km) will connect Bhadrapur in the East to Dodhara in the Far-West. The long awaited Mechi-Mahakali electrified railway (1205 km) will further contribute towards increased connectivity of people and places as Nepal progresses toward prosperity aided by roadways and railways.

Although this is great news for any developing country, one cannot ignore the rate at which natural landscapes are being fragmented and wildlife habitats are shrinking in the name of development.

Roads that are being planned and constructed also cross transboundary landscapes and bisect what have been identified as major wildlife corridors. In the absence of proper monitoring and precaution, the highways that are being envisioned now will most certainly increase Vehicle Wildlife Collisions, turning what we call connectivity means into death traps that could risk not only wildlife but humans as well.

In the given scenario of growing VWC today, wildlife-friendly structure backed by proper planning and scientific studies especially in areas wild animals use as crossings need to be built, so that the effect of projected infrastructures can be minimized. As a positive step, some efforts are also being made in national parks like Bardia to reduce cases of VWC. These include time cards for vehicles plying on the national highway that traverse through the national park, reflective signboards, and awareness activities for drivers, among others. Nevertheless, the problem of VWC elsewhere is seeing an increasing trend.

The Department of Roads recently drafted “Wildlife friendly Linear Infrastructure Guideline” which is believed to be a milestone undertaking as it shows that conservation is becoming a priority for development stakeholders of Nepal. Duly following the guideline that shows a clear linkage between the requirements of crossing zones based on the frequency of wildlife movement at various locations of Nepal will certainly result in a thoughtful and enhanced approach towards linear infrastructure development.

The author is the senior program officer of the infrastructure program at WWF Nepal

You May Like This

Sustain, accelerate, innovate

The WHO South-East Asia Region has made rapid progress in health and well-being. The journey continues ... Read More...

In defense of private schools

Why can’t an entrepreneur open a private school and make profit in the process? Why don’t we let the market... Read More...

Reconciling security and growth

“America First” approach taken by the US will strengthen China’s own hardliners, who will push to emphasize national security over... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment