OR

Biswas Baral

Biswas Baral has been associated with Republica national daily as a journalist since 2011. He oversees the op-ed pages of Republica and writes and reports on Nepal's foreign affairs. He is a regular contributor to The Wire (India).biswas.baral@myrepublica.com

More from Author

If domestic politics are a major determinant of international relations, a few factors will disproportionately influence Nepal’s foreign policy.

Our two neighbors perfectly illustrate how a country’s foreign policy is primarily driven by domestic concerns. China’s recent aggressive posture abroad, particularly on the South China Sea and with Japan and India, owes a lot to the upcoming shakeup of the Communist Party of China planned for later this year. In this party congress, President Xi Jinping wants to stamp his authority as the most influential Chinese leader since Mao.

For this, it is important that he be seen by his party colleagues as decisive abroad.

In the case of India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is also trying to consolidate power ahead of the 2019 general elections. While Xi wants to cement his place as the strongest Chinese leader after Mao, Modi seeks to be the most influential leader of post-independence India. He has already gone some way towards this goal by shepherding the unprecedented victory of his party in the 2014 polls. This also explains, in part, his ‘viceroy-like’ glam foreign tours, which he thinks adds to his domestic aura.

Perhaps the Indo-China standoff over the Doklam plateau would not have dragged for 10 long weeks without so much at stake for both Xi and Modi. With major political changes just around the corner, neither could afford to be seen as weak domestically. But nor did they want another debilitating war. This explains the prolonged impasse in search of a mutually-agreeable solution.

Historically, too, power projections abroad have helped boost the domestic image of Indian and Chinese leaders. This was as true of Nehru and Indira Gandhi as it was of Mao and Deng Xiaoping. And the same has been the case with Nepal. Shah rulers found it convenient to declare war on Tibet or the British whenever they felt a threat to their crown. The Ranas maintained ‘splendid isolation’ to keep Nepalis away from the light of education and idea of self-rule. The democratic rulers after them also expertly played one neighbor against another to get to power and stay there.

China for elections

This use of the international means for domestic ends continues to this day. KP Sharma Oli and his CPN-UML party have successfully cashed in on the anti-India sentiments generated by the border blockade by projecting themselves as sole bulwarks against the big brother next door. Oli also realizes that being seen as pro-China goes down well among the electorate alienated by India.

Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, after badly bungling the geopolitical game in 2009, has now emerged as another adept ‘balancer’ between India and China. Prime Minister and Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba took a while to realize the electoral utility of closer ties with China, but recent actions suggest he too understands the costs of being marked as ‘India’s man’.

Even the Madhes-based parties, together one of four major political forces in Nepal, and which have traditionally been known to have a soft spot for India, are having second thoughts. They find it increasingly hard to trust India, which, after all, abandoned them midway during the border blockade.

But if domestic politics are a major determinant of international relations, a few key factors will disproportionately influence Nepal’s foreign policy in the days ahead.

First, there has to be a degree of political stability in Kathmandu for Nepal to be trusted abroad. But with the kind of electoral system we have devised, we will have unstable coalitions ruling Nepal far into the future. Foreign powers as such will continue to struggle to deal with the ever-changing cast of characters in Kathmandu.

Chinese President Xi had to cancel his planned Nepal trip when the government of Oli was toppled at the end of 2016. Chinese have repeatedly said that above all they want political stability in Nepal so that the government in Kathmandu at least has enough time to implement its agreements with China. Before Modi came to Nepal in 2014, a sitting Indian prime minister had not visited Kathmandu for 17 years, for similar reasons.

As Nepal’s foreign relations deteriorated, foreign actors started looking for all kinds of ways to try to influence events here. The ‘micromanagement’ of Indian foreign ministry bureaucrats and spy agencies greatly increased after the 2006 changes; and following the closer of Tatopani after the 2015 earthquakes, Chinese security organs have also been especially active. Meanwhile, western powers, particularly the US, have used prolonged instability in Nepal to further boost their surveillance against communist China.

Consensus for trust

One way Nepal can instantly increase its credibility and also minimize undue foreign meddling, even in a state of constant political flux, is for its major political actors to develop common stands on core foreign policy concerns. During his recent China visit, Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Krishna Bahadur Mahara disclosed how he had been able to establish political consensus on bringing Chinese railway to Nepal. Why can’t there be similar cooperation and understanding on other foreign policy issues?

Regime stability in Kathmandu is also closely tied to the question of broader political stability, which in turn hinges on implementation of the new constitution. Without a permanent settlement with Madhes, a root cause of political instability will remain intact. Institutionalized corruption and the unofficial ‘permit raj’ are further deterrents for credible foreign actors. One senior Chinese official in Kathmandu was recently complaining with this columnist that the plethora of bureaucratic hurdles Chinese projects in Nepal face, sometimes delaying them for years, could have been cleared in China within a single week.

Here I am reminded of eminent Indian historian Ram Chandra Guha who fears India is becoming an ‘election-only democracy’ rather than a full-fledged ‘electoral democracy’. Yes, just as it is for India, having free and fair elections is vitally important for Nepal. But completing the three sets of elections by the January 21, 2018 constitutional deadline will only be a start of Nepal’s journey as a fledging federal democratic republic. As Guha hints, a functioning democracy entails so much more: things like responsible political parties, guarantee of minority rights, equitable sharing of resources, freedom of religion, freedom from hunger and want, freedom from discrimination, investment climate, clean governance and rule of law.

As the examples of President Xi and Prime Minister Modi show, personalities matter in foreign policy. Yet it could be argued that without stable politics and sound economy back home, they would have been unable to successfully venture abroad.

But even in India and China, their leaderships don’t get everything right. Nepal for one could start on its new journey abroad by establishing the all-important political consensus on vital foreign policy issues.

biswasbaral@gmail.com

You May Like This

Ensuring Food Safety Amidst Challenges

Kathmandu is renowned for its heritage and historical significance, attracting many tourists. The capital city offers an enormous variety of... Read More...

Modi's Moscow Mission: “Enduring and Expanding Partnership”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi chose Russia for his first bilateral visit (July 8-9) in his third term. This is... Read More...

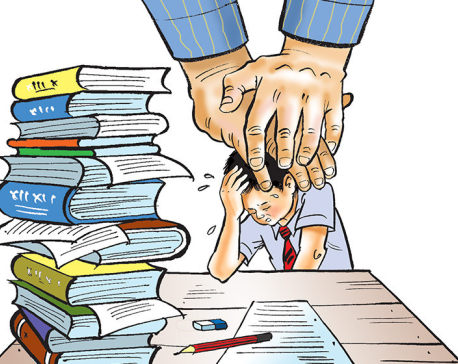

Challenges Facing the Nepali Education System

By the end of 8th grade, most schools stop teaching subjects like music, dance, art, and even sports, the very... Read More...

Just In

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

- Singapore now holds world's most powerful passport; Nepal stays at 98th

Leave A Comment