OR

Dogs see the world very differently from human beings — here's how it works

Published On: April 2, 2018 02:21 PM NPT By: Agencies

As humans, how we perceive the world is how we define our own reality. And for the vast majority of humans, perception is handled through sight.

Your hearing, and your senses of smell, taste, and touch also play roles — no doubt — but sight is the most immediate way we experience the world around us.

Your hearing, and your senses of smell, taste, and touch also play roles — no doubt — but sight is the most immediate way we experience the world around us.

This isn't the case for dogs.

The adorable snout on your pup isn't just for petting — dogs "see" the world with their nose first. "We assume that non-human animals' perception would be kind of like ours, but simpler," dog cognition researcher Dr. Alexandra Horowitz told me in an interview last year.

But that isn't the case. Instead, dogs "see" the world through smells. Here's how it works.

"It's really hard to get outside our perspective."

Because our perception of the world colors our perception of how others see the world, we assume that dogs primarily perceive the world through sight. But it's not so hard to understand — and even experience — the concept of smell as a primary input.

Because our perception of the world colors our perception of how others see the world, we assume that dogs primarily perceive the world through sight. But it's not so hard to understand — and even experience — the concept of smell as a primary input.

"You could think of it as just another perceptual modality," Horowitz told me. "You can close your eyes. You're still having an experience as a human, and it's transformed in some ways. But there's still a room. There's still a reality — a room that you can hear, you can smell, you can touch. And even though it's not one that we're that familiar with, we're still co-existing."

That's the first way to understand how dogs see the world — close your eyes, maybe cover your ears with sound-canceling headphones. Now take a sniff! As humans, our sense of smell is nowhere near as adept as that of dogs — but you can begin to understand how a dog perceives the world. Maybe you smell something delicious, or something rotting, or the sterile blow of an office air conditioner.

"We basically have a cloud of smell around us. That's interesting, because it means a dog can smell you before you're really there," Horowitz said. "If you're around the corner, your cloud of smell is coming around ahead of you."

"Ultimately, their bigger interest is smell than vision."

Which isn't to say that dogs don't literally see you — their eyes are another form of input, just not the primary one. "They might look at someone with their eyes; as you approach, they look at you," Horowitz said. "But then once they've noticed that there's something with their eyes, they use smell to tell that it's you. So they sort of reverse that very familiar use of ours."

Which isn't to say that dogs don't literally see you — their eyes are another form of input, just not the primary one. "They might look at someone with their eyes; as you approach, they look at you," Horowitz said. "But then once they've noticed that there's something with their eyes, they use smell to tell that it's you. So they sort of reverse that very familiar use of ours."

And that's crucial to understanding how dogs see the world.

You, as a human, might smell something delicious and then use your eyes to look around to locate the source of that delicious smell. "Ah, it's pasta sauce slowly coming together on a stove!"

For dogs, the opposite is true. Or, as Horowitz put it:

"We smell something and then when we see it we're like, 'Oh yeah, that's it. That's what it was. It was cinnamon buns.' And dogs when they see you, they're like, 'Okay, that's something to explore, I'm gonna smell it. Oh yeah that's Ben.'"

"Instead of all the things that are bouncing into my eyes when I sit in a room, I'm just perceiving that room through things — molecules of smell. That's really the transformation you have to make."

We perceive depth, as humans, through stereo vision — our two eyes triangulate on the world around us, and our brain converts that video feed into three dimensions. That same concept applies to dogs, except — once again — it's through scent rather than sight.

We perceive depth, as humans, through stereo vision — our two eyes triangulate on the world around us, and our brain converts that video feed into three dimensions. That same concept applies to dogs, except — once again — it's through scent rather than sight.

"Where something is in a room, or what something even is, kind of changes a bit if you imagine it as an olfactory precept instead of as only a visual precept," Horowitz said. To translate that a bit, your perception of the world fundamentally changes if it's viewed through the lens of scent.

It means not only do you perceive what's immediately around you, but also what was once around you and what's coming up. In this way, how dogs perceive the world is actually moredeveloped than humans — their sense of smell doesn't just alert them to the present, but it alsotravels through time.

Dog noses are the perfect shape for identifying smell.

Human noses aren't just structurally different from dogs — they're also functionally distinct.

Human noses aren't just structurally different from dogs — they're also functionally distinct.

Due to the shape of dog noses, the way they intake air and expel breath encourages a more developed sense of smell. It's actually the latter effect that enables more new odor molecules to be absorbed on the next breath — and it's the same reason why dogs get so ridiculously close to things they're smelling.

As a dog expels breath from their nose, an air current is created that actually kicks up more new odor molecules. As the dog takes its next breath, it's absorbing the molecules that it kicked up when expelling its last breath. Through this system, dogs are not only sniffing but actively enabling "better" sniffs.

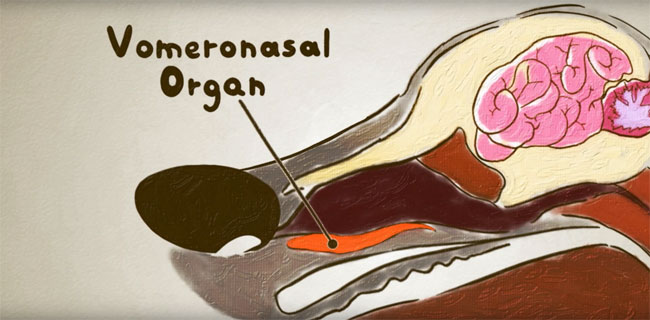

Dogs have far more smell receptors than humans, and they also have an organ we don't that's specifically used for smell perception.

Beyond the shape of a dog's nose determining how well it can suss out scents, the internals are crucial.

Beyond the shape of a dog's nose determining how well it can suss out scents, the internals are crucial.

First and foremost, there are 60 times more "olfactory receptor cells" in a dog's nose than in a human's nose. Think of it like cups for catching rain: If you have five cups set up to catch rain, you'll catch five cups worth; if you have 300 cups set up to catch rain, you'll catch 300 cups worth. That is the difference, roughly, between humans and dogs in terms of scent perception.

And that's not all! There's also the "vomeronasal organ," which is another means of deciphering information from scent molecules. "They're also getting information in the vomeronasal organ," Horowitz told me. "And to get information there you have to actually absorb some of the molecules."

This is why a dog might eat something it shouldn't — it's an attempt to learn more about that object. It also might just be hungry and ambitious.

"Smell is just information for them, the same way that we open our eyes and we see the world."

Notably, dogs are unlikely to classify scents as "good" or "bad." In the same way you don't look at feces and shudder, a dog is unlikely to sniff feces and immediately back off.

Notably, dogs are unlikely to classify scents as "good" or "bad." In the same way you don't look at feces and shudder, a dog is unlikely to sniff feces and immediately back off.

"We don't have a great vocabulary for smell, so we do end up saying that's a really great smell, or that's a horrible smell," Horowitz explained. Unless you're someone who specializes in scent — a perfume scientist, for instance, or a wine sommelier — you're unlikely to have a highly-developed sense of smell when it comes to descriptions. I smell fresh baked bread and react with, "That smells delicious!" A dog might react with, "That smells like flour and water and yeast and heat."

Horowitz described the effect as such: "We might try to say what the smell is of, but we're often not even good at that. 'I recognize that smell, I don't know what it is.' Since we don't have a vocabulary, and most of us aren't primarily using smell, we tend to think of smells as good or bad."

But for dogs, it's just information. That's why they put up with your post-workout stink in the same way they're happy to stick their nose directly into a pile of poop. No judgment — just information.

You May Like This

People with depression use language differently – here's how to spot it

From the way you move and sleep, to how you interact with people around you, depression changes just about everything.... Read More...

World Cup 2018 qualifiers -- as it happened

CARDIFF. Sept 6: Spain put eight goals past Liechtenstein. Wales netted four against Moldova. Italy scored three in Israel. ... Read More...

Albania has to wait to see if it qualifies for next round

LYON, France, June 20: It's going to be a long three days for Albania as the small Balkan country waits... Read More...

Just In

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

- NC defers its plan to join Koshi govt

- NRB to review microfinance loan interest rate

- 134 dead in floods and landslides since onset of monsoon this year

- Mahakali Irrigation Project sees only 22 percent physical progress in 18 years

Leave A Comment