Eleven Minutes started with an intriguing dedication to a stranger Coelho met in Lourdes, France. The stranger told him that Coelho’s books made him “dream.” Coelho states, “I felt really frightened, because I knew that my new novel, Eleven Minutes, dealt with a subject that was harsh, difficult, shocking.”[break]

He follows this up with an extract from the Bible, when a prostitute washes Jesus’ feet with her tears, wipes them with her hair, and anoints them with ointment. Then comes the Hymn to Isis from Nag Hammadi, a paradoxical and powerful poem. Finally, Eleven Minutes opens with two Once upon a times.

The first ‘Once upon a time’ is a disclaimer: “‘Once upon a time’ is how all the best children’s stories begin and ‘prostitute’ is a word for adults. How can I start a book with this apparent contradiction?...”

The second ‘Once upon a time’ introduces Maria, the prostitute. We meet her past in Brazil, a young, innocent girl who dreams of her Prince Charming. The story is told simply, sometimes too simply. Coelho invests time in explaining that this is a difficult subject but he seems to be dealing with the main character too easily. Granted, investing too much in her early years may turn out to be unnecessarily complex but the predictability underlining the structure and development of Eleven Minutes can be a letdown.

The setup tells all: it is about feminism, sexuality, the nature of human physical and emotional relationships – and like Coelho’s other books – the search for self. Unlike the other books, he deals with sex on another level and writes about it as the path on which Maria embarks. While on a vacation in Rio de Janeiro, she meets a Swiss businessman and inadvertently signs a contract agreeing to be a dancer in a Geneva nightclub. Geneva has its seedy side and Maria discovers quickly that not all is okay in this “city with two names.” She leaves the club but ends up being a prostitute in Rue de Berne.

For a long time, it seems she may get out of the seedy life through sheer intellect. She frequents the library to help increase her knowledge of her profession, of human psychology (she realizes that her clients come to her more out of loneliness than physical need), and farm management (she wants to return to Brazil and own a farm). She seems to question all that surrounds her, but then you come to the ‘diary entries’ at the end of each chapter and realize that the image created of her and what the character really might be are separate entities.

Maria is observant and intelligent, but Coelho sets off the same path that we see in Hollywood chick flicks. She meets a rich, famous artist. This section is clumsy and heavy with symbolism: she meets him at a cafe which has a sign outside that says Road to Santiago (pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella in Spain, where Coelho himself is stated to have had his spiritual awakening). The artist insists on drawing Maria because she has an “inner light.” The artist’s name is Ralf Hart.

Here on, despite the pain Coelho took in setting up, the beautiful extracts he used, the special dedication, the baring of his own fright and difficulty in dealing with the “shocking” nature of the subject, he seems to veer toward the predictable path.

Spoiler alert: if you don’t want to know the end, stop here.

Maria ponders on why she wants to stay in Geneva. She thinks of the difference between physical and emotional love. She experiments with pain and pleasure, invests in building a meaningful relationship without expectations. She buys her ticket to Brazil, clears her Swiss bank account, packs her suitcase and goes to say goodbye to Ralf. This scene we get from her last diary entry, which is an odd choice, considering the nature of the prose. They spend the night together and when she leaves in the morning, it’s obvious that Coelho is aware of how close it comes to being a Hollywood scene and he consciously seems to want to stay away from it.

“That’s how it always happened in films: at the last moment, when the woman is just about to board the plane, the man races up to her...‘The End’ appear on the screen, and the audience knows that, from then on, they will live happily ever after.”

Then Coelho decides to show you what happens next, unlike in films. Except it’s exactly like the films – only one stopover more. Ralf shows up in the Paris airport while Maria is waiting for her connection – with a bunch of roses and eyes “full of light.” He says, “We’ll always have Paris.” (the famed line from Casablanca).

Why did Maria, after everything, need a rich, handsome, famous, white artist to “save” her even though she technically has her own money and is supposedly choosing love over all else? Why did Coelho name the artist Ralf Hart? Why did Maria need men to teach her the paradoxes of life and the only other woman friend she has, a librarian, is also as clueless as her? And why did Ralf have to go to Paris if he was going to show up with a bunch of roses and a Humphrey Bogart line?

Coelho knows the pitfalls and he deals with the complexities of the body, heart and mind with ease. However, the story and its ending don’t hold up to the investment he made in the beginning. I’m glad I read his other books before, but I doubt I’ll be picking up another for a while.

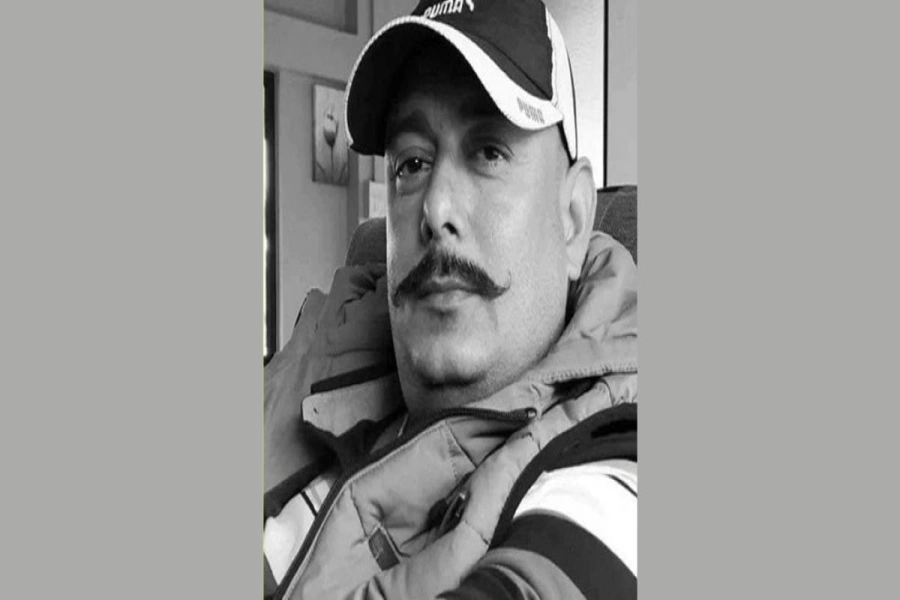

Nawazuddin Siddiqui receives praises from author Paulo Coelho