KATHMANDU, Jan 4: Once regarded as a driver of economic growth and rural prosperity, the nation’s cooperative sector has become synonymous with swindling and disorder. Many depositors have been victims of massive savings fraud, with government authorities failing to recover lost funds on time. Swindlers stole a total of Rs. 87 billion (about 630 million USD), affecting tens of thousands of families who deposited their savings in cooperatives.

The scale of the problem is truly shocking, both in terms of the amount of money defrauded and the political power that some of those involved used to avoid prosecution. Cooperative funds scams involve individuals such as Rabi Lamichhane, a former media figure and now a well-known politician, and others with political ties. Ichchharaj Tamang, a former UML parliamentarian, embezzled billions of rupees in cooperative savings, leading to his imprisonment; RPP parliamentarian Geeta Basnet and the wives of several Congress and UML leaders are on the run. The involvement of people in positions of power, as well as the amount of embezzled funds, demonstrate the worrying link between political power and savings scam. Investigators accused them of stealing billions of rupees through shady schemes that bankrupted hundreds of cooperatives and harmed depositors. Even though legal action is being taken, victims are apprehensive that they will not receive justice or their deposits in a timely manner.

Fraud in our nation’s cooperative sector has ranged from outright theft to risky investments in areas such as real estate and cryptocurrencies. Some cooperative operators created cooperatives solely to defraud unsuspecting savers; they transferred deposits to personal accounts and invested many in speculative businesses like the stock market and bitcoins. Poor management skills, exacerbated by the nation's economic slowdown let down many cooperatives. When rumors about cooperative scams spread like wildfire, panic withdrawals caused many cooperatives to close.

This problem raised an important question: how could such a large sector fall apart despite having laws to govern them? A lack of strict control and supervision can be an apt answer. Nepal has over 30,000 cooperatives of various types, but the rules are not strictly enforced, and there is insufficient funding to support the monitoring process. The government's Department of Cooperatives lacks the resources and personnel required for proper supervision of these entities, which leaves enough room for abuse and fraud. Furthermore, some supervisors are affiliated with the cooperatives they are supposed to supervise, indicating a conflict of interest.

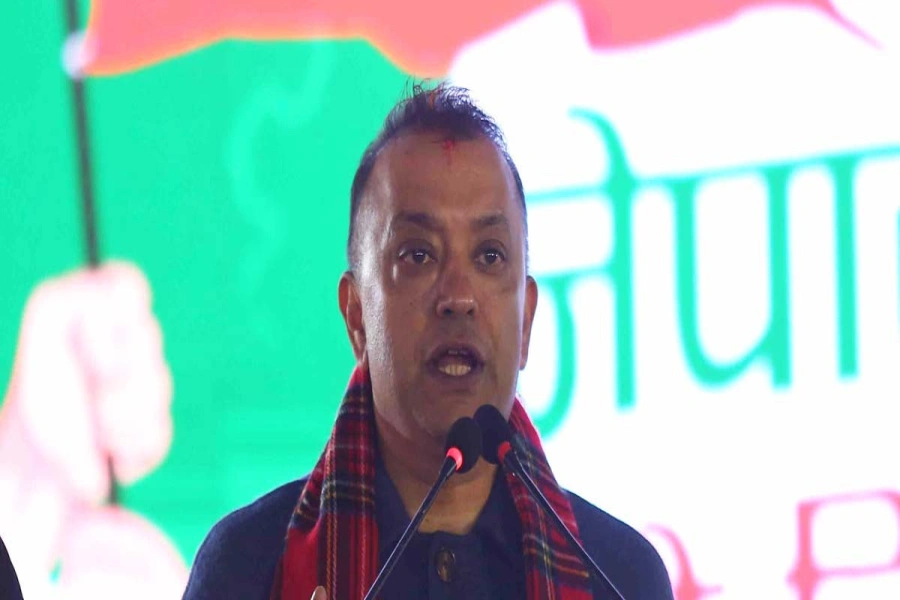

Police publicize ex-chairman of Kantipur Savings and Credit Coo...

The biggest scam to hit the nation has made its victims the individuals that include retirees hoping to receive benefits, low-wage workers, vendors, housewives and farmers along with many professionals, who saved every penny they earned in the hopes of earning handsome interest on their deposits. They have been severely impacted by the illegal acts of operators who enticed many of them by promising high interest rates on savings. The inability to recover these lost savings has put many depositors in serious financial trouble.

Efforts to address the current problem appeared minimal. While the amended Cooperative Act is encouraging in terms of prioritizing modest deposit refunds (up to NPR 500,000), the issue of recovering huge defrauded funds in time remains. Delays and court challenges have impeded the sale of cooperative assets and the recovery of bad debts. These initiatives may benefit some victims, but without a comprehensive effort, they may not produce the desired outcome.

How might our authorities address this crisis?

First, the government should take aggressive steps to reclaim and refund cash. To locate and recover diverted monies and assets, a dedicated task force comprising financial specialists, legal consultants, and independent inspectors must be assembled. This group should be permitted to bypass bureaucratic red tape in favor of focusing solely on victim compensation. Small deposits require special care. If necessary, the government should swiftly return deposits of up to NPR 500,000 with public funds, viewing this as a civic responsibility. These monies can be recovered progressively over time by liquidating cooperative owners' and borrowers' assets. People found guilty of fraud must face severe punishment. This penalty should include not just jail, but also complete confiscation of their assets as recompense for victims. We need major reforms to avoid repeat calamities.

The establishment of the independent self-governing National Cooperative Regulatory Authority, which will oversee and monitor cooperatives engaged in savings and credit activities, has boosted victims' optimism. In addition to establishing a categorization system for cooperatives at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels, the authority requires that cooperatives engaging in savings and loans be registered. Similarly, it bans a person from belonging to multiple cooperatives of the same sort. It also establishes term restrictions for directors of cooperatives that participate in savings and loans, as well as federal savings and loan limits for cooperatives. What is crucial is that it has established standards for repaying funds up to Rs 500,000 placed in cooperatives.

Finally, political engagement in cooperatives must cease; leaders involved in these schemes should be barred from holding public office until they can demonstrate their innocence. The combination of politics and financial misbehavior undermined public trust. The cooperative problem raises a moral quandary and demonstrates weaknesses in a system designed to build communities. Recovery of swindled monies is possible, but it requires courage, determination, and understanding from both government agencies and all stakeholders.