OR

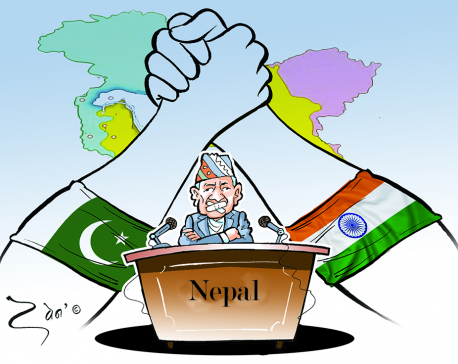

Between the giants

Published On: November 21, 2018 01:30 AM NPT By: Eric Fan, Claire Crane and Bikash Gupta

Eric Fan, Claire Crane and Bikash Gupta

Fan is an undergraduate student at Emory University, Crane at Middlebury College, and Gupta at Soka Universitynews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

Sandwiched between India and China, Nepal needs to learn from past experiences of others and gather lessons in dealing with these powers

One well-known Chinese saying goes, “Want to become rich? first build the road.” Indeed, it has been a common Chinese experience that infrastructure brings about development, and whenever possible, China never hesitates to export that model.

The relationship between China and third-world countries extends back to the era of Mao, specifically China’s role in the financing and construction of TAZARA railway linking Zambia and Tanzania. However, this relationship has been renewed and expanded in the 21st century. Infrastructure investment is a crucial component of China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, the ambitious plan launched in 2015 that intends to restore China’s once thriving Silk Road and link Asia, Africa, and Europe through transportation and trade.

China is an attractive business partner to many less-developed nations, given its stated commitment to ‘no strings attached’ investment whereas the United States appears more interested in governance and humanitarian aid, encouraging the Western-style democracies around the world, or funding public health initiatives as means of development. China looks to its own rapid progress as the ideal model, and regards economic reform as the best way forward.

The world’s largest exporter of goods since 2009, China now has started to promote its own model of development, which inevitably comes into conflict with the economically liberal and politically democratic model championed by the West. In his recent speech at the Boao Forum in Hainan, Xi Jinping claimed that “there exist more than one road toward modernization,” and that “all roads lead to Rome.” More explicitly, in his report of the 19th National Congress of Communist Party of China, Xi promised to contribute “China wisdom” and “China plan” to the rest of humanity.

Furthermore, while American aid is often lost or misappropriated in a maze of NGOs and government bureaucracy, Chinese money is known to produce swift and tangible results. The Chinese government prioritizes concrete indicators of development, such as infrastructure projects, and then manages the financing and construction processes with Chinese state-owned firms, thereby avoiding the red tape and disruptions that often stymie construction projects that are negotiated between public and private agents.

Taking this opportunity, China also pushed for a more ambitious strategic goal. In 2017, the same year when the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway was finished, the Chinese support base in Djibouti opened and became the People’s Liberation Army’s first overseas military base. Although the Chinese government has always proclaimed non-aggression, the move clearly demonstrated its determination to expand its sphere of influence on the African continent and to protect Chinese interests including investments abroad.

Criticisms of this so-called ‘China model’ include a lack of transparency, inefficient urban planning, and the inability to transfer construction or operation over to local workers. Many also warn that despite their professed principles of anti-hegemony and non-interference, the Chinese offer loans that their partners will be unable to repay.

The case of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port provides a cautionary tale. In December 2017, the pork barrel project spearheaded by former Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa was quickly handed out to China on a 99-year lease. Examples like this feed into a narrative that China is investing in nothing but its own strategic expansion.

Mutually respecting each other’s sovereignty has long been a Chinese diplomatic doctrine, but when borrowers fail to pay back debts, they have very few options except to give China some shares and even complete control in their key infrastructures. A 99-year lease in the case of the Hambantota Port reminds people of the lease of Hong Kong during China’s “century of humiliation.” The example illustrates the dangers at stake in such massive foreign investment projects. While blueprints promise local jobs and a ticket into a global economy, the reality may be a loss of autonomy.

The case of India

China has been an enigma to Nepal. Yet, cultural exchanges are peaking now and almost one-sided as Chinese come to Nepal and leave behind concrete changes. Thamel’s de-facto adoption of Renminbi currency can be one of them.

On the other hand, Nepal has a history with India mired in mutual suspicion that has affected the perception of Indian aid and investment in Nepal. India doled its first official aid to Nepal after 1952 and the latter remained India’s priority for 20 years. The Indian assistance would include grants and training to Nepali bureaucrats and technocrats. However, cases such as the presence of Indian Army—a part of Indian military assistance program to train Nepal Army—on the Nepali turf captured the left’s imagination of India as expansionist.

The subsequent generation reconciled this image of India with a real embargo in 1989 and most of them would later grow up to see the alleged Indian embargo of 2015. Dizzying nationalism in a changing country would contribute to the election of “nationalist communists” in 2017, unapologetically friendly to China.

In Nepal, Indian aid is met with scrutiny in public sphere. While Indian bureaucracy perceives Nepal as ungrateful, Nepalis perceive Indian attitude as forceful, compelling Nepal into accepting lopsided agreements. Monalisa Adhikari has written about India’s failure to “win the hearts and minds of the [Nepali] people.” Indian aid is not “refused” but “resisted” in the country and has given rise to “anti-Indian sentiments.” “Gaps in planning, processes, modalities and perceptions of India’s motivations” has resulted in the rise of such sentiments, she argues.

However, as China makes inroads to the South Asia, India has also increased its largess in the region. With the “neighborhood first” policy, it has counterattacked increasing Chinese influence. In recent years, India has consolidated its historical ties with neighbors that it took for granted. With foreign assistance to Iran and Afghanistan in the North West, reach out to Mongolia in the North, ferocious India-ASEAN ties in the South East, and military aid to island nations in the South, India is trying to span its own large circle of influence.

Western think tanks have lauded India’s foreign aid in conflict-ridden countries, especially Afghanistan. However, India’s performance may not be impressive in other countries. Moreover, such aid-diplomacy stands as an opportunity for India to trumpet itself as a beacon of ‘democracy’ and distinguish as much from China—the construction of Kabul parliament building, for example, is an impeccable showcase.

India has pledged more than $ 3.1 billion in Afghanistan since 2001 but Afghanistan does not top the chart among the recipients. Bhutan received nearly 3/4th of India’s aid during 2015/16. This “bribe aid” is diplomatic maneuver to further its influence in the geo-strategically important country. In Nepal, India invested fewer than four percent of total foreign assistance during 2015/16 and was outweighed by China in real numbers during the same fiscal year.

Studies have shown that India concentrates its foreign investment and aid in neighboring countries. Indian aid model is different from the west, which attaches conditionalities, rooted in neoliberalism, governance, democracy, and human rights. Indian developmental model is strategic in that it seeks to prioritize regional connectivity over idealistic values.

Yet in recent times, it has openly espoused the idea of democracy. This overt support for democracy has at times prevented it to wield influence in countries that are backsliding to authoritarianism. For example, India’s commitment to human rights and demand for a release of former President has led to a rocky relationship with the government in Maldives—where China has quickly come to fill the vacuum. Besides this, Indian model has experienced shares of technical and administrative challenges. Indian projects have failed to complete on time. Currently, India-led projects have been experiencing problems in the Maldives and Bangladesh over land acquisition and unavailability of credit on time.

On the other hand, China has left more diplomatic footprints in the world than India. China trades with political establishments and least cares about the messy political life in the country. India sometimes does, but risks infuriating the nationalist base in the country. As ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP) seeks options besides India, it is also cognizant of the Chinese model and has demonstrated euphoria as well as unease in the past few months.

Choose wisely

Nepal, like Sri Lanka and Djibouti, is a small nation positioned at a strategically important location. Such nations find themselves easy targets of numerous regional powers.

Sandwiched between India and China, Nepal needs to learn from past experiences of others and gather lessons in dealing with these powers.

The Chinese model of development might have its uniqueness, but the essential objective of any model is necessarily to increase influence and project power in the region, regardless of the methods used. As carrots and sticks begin to knock on Nepal’s door, it should be able to make right choices and act as the master of its own fate.

Fan is an undergraduate student at Emory University, Crane at Middlebury College, and Gupta at Soka University

You May Like This

Testing times

With the new developments in Kashmir, Nepal may have to listen to and deal with the pressures and persuasions from India,... Read More...

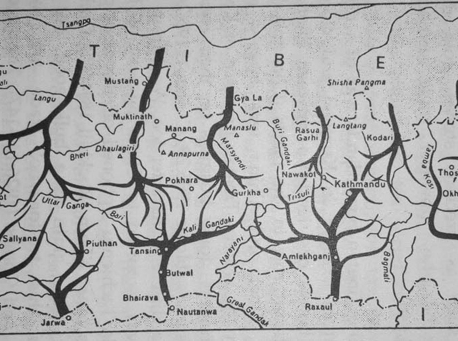

Where we failed on trade

Major trade routes Nepal struggles to open with China today were customary trade routes to travel and supply goods to Tibet... Read More...

Nepal should hedge

How should Nepal respond to a changing security context and handle pressures from greater powers like India and China? ... Read More...

Just In

- Sunkoshi-Marin Diversion Project’s tunnel construction nears completion, breakthrough scheduled for May 8

- Govt tightens security arrangement for Third Investment Summit 2024

- Pesticide residue found in vegetables in Nepalgunj

- Aam Janata Party and Samajwadi Jana Ekata Party merge

- 1,600 participants confirmed for Nepal Investment Summit

- Ilam-2 by-elections held peacefully, vote count likely to start tonight

- NEA schedules five-day power cut across Kathmandu Valley for underground cable installation

- Hundreds of passengers including foreign tourists in distress as poor visibility halts flights to and from PRIA

-1200x560-wm_20240427144118.jpg)

Leave A Comment