The United Nations has been vital to Nepal’s modern era, marking the vulnerable country’s international standing through membership in the organisation in December 1955, providing development advisory and assistance over the decades outside the prism of geopolitical considerations. Nepal, too, has assisted the United Nations, most notably as the country now providing the second largest contingent to the UN’s peacekeeping force.

For a time, though, this relationship took a beating. There were several factors, but mainly it was the insensitivities of the leadership of the United Nations Mission to Nepal (UNMIN), which helped ignite a reactive political class and bureaucracy in Kathmandu. The passage of time has provided some healing, but proactive measures are needed to rebuild empathy, and a visit of the secretary-general provides an opportunity even though there has been little time for any of the stakeholders to plan, least of all Nepali civil society.

It is important for Nepal that the relationship with the world body is normalised at an accelerated pace, because Nepal needs a friendly arm amidst the escalating great-power rivalries of Asia and globally, and with it the clamour for Kathmandu to take sides. The planned visit of UN secretary-general António Guterres on October 29 is an opportunity to revitalise the UN-Nepal connection and prepare for the future.

A curiosity

Every first-time plenipotentiary to Kathmandu must seek first-hand knowledge on Nepal and its recent experiences, particularly the conflict it is trying to put behind, for neither journalistic nor academic writings are adequate for a country that functions outside the colonial language discourse. Further, as is well known, the institutional memory of the international agencies and diplomatic corps is notoriously wanting.

Right off, while it is a privilege for a country that has been shunned for long by world leaders to receive a high personage, it is a curiosity that the UN secretary-general has chosen to visit Nepal at a time when it is ruled by a prime minister whose party has 32 seats in a parliament of 275 (11.1%) and whose hold on power is precarious. Maoist chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ does not represent the choice for head of government in the people’s ballot of November 2022. He is in the prime minister’s seat because of the dog-eat-dog nature of Nepal’s forever full-time politicians, competing embassies with geopolitical urgencies, and Nepal’s mix of direct-proportional electoral system. The public does accept the de jure reality and is simply waiting for the wheel to turn – one may be properly legal but not carry legitimacy.

Thus, there is a reading of the collective mind, with which this writer agrees, that everyone is simply waiting for the house of cards to collapse. Meanwhile, the Dahal regime has entered deeper into the swamp of corruption and mal-governance than previous ones, including derailing investigations into several cases of loot relating to gold smuggling, fake refugees and government land made private; it cannot hold its head high among international peers; it is happy with the weakening of state institutions and revels in defying Supreme Court injunctions; it lacks economic vision for a country that is brimming in natural and human resources; it lacks the credibility to handle proximate challenges to social harmony; and, it does not seem energised to battle those working to engineer a collapse of the 2015 Constitution. No other head of government in 73 years since the end of the Rana autocracy is this much driven by personal greed rather than national ambition, and publicly willing to be ‘comfortable’ with whichever neighbouring government will back his political career.

The Lumbini garden

Among the finest contributions of the United Nations organisation in Nepal was triggering the preservation and development of Lumbini and its surrounding area. The management of the nativity site of the Sakyamuni, however, presents an example of the inadequacies of Nepali governance, and where the UN may want to re-engage itself.

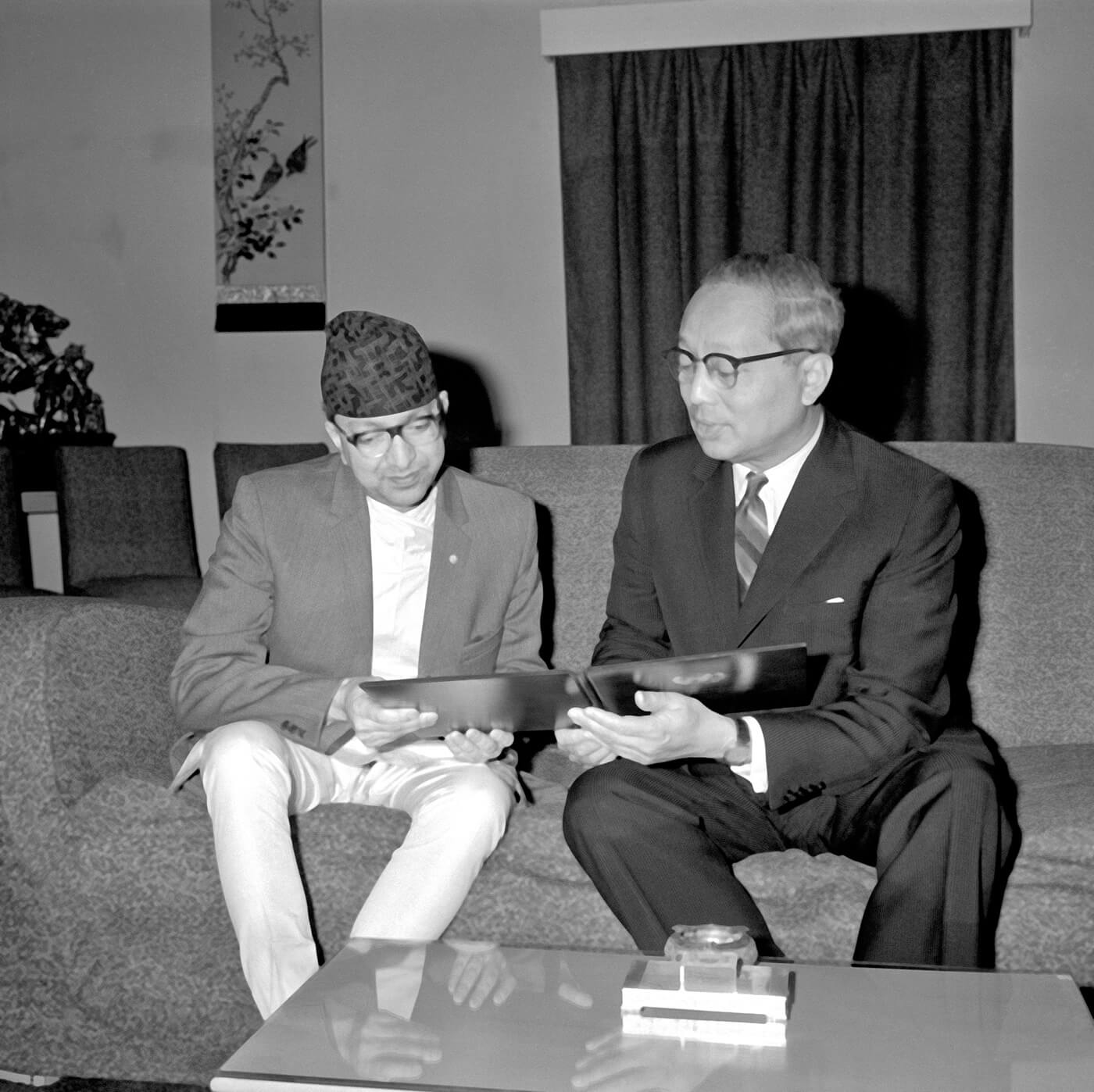

All secretaries-general who have arrived in Kathmandu have made the trip to Lumbini, and one expects Guterres will, too. The third incumbent, U-Thant, arrived here in 1967, wept with emotion, and vouched to provide support to develop the place. King Mahendra enthusiastically took up the idea, and the plans presented by architect Kenzo Tange have saved the immediate area from being commercialised beyond repair, managed as it has been by political appointees who care little about preserving the spiritual sanctity of a site that is heritage of all humankind.

The very first visit to Lumbini by a UN head was in 1959, when the second Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold touched down and also wrote a haiku, published in a posthumous collection:

Like glittering sunbeams

The flute notes reach the gods

In the birth grotto.

While the sanctity of Lumbini was clearly felt by Hammerskjold, the Nepali custodians have been lax over the years. The challenge today is to save Lumbini from over-marketing at the cost of spirituality, ratchet down competing Buddhist nationalisms and inter-sect competition, and find a way to tackle the projected massive increase in footfall of pilgrims and tourists.

U-Thant with King Mahendra in Lumbini

Lumbini is the only heritage site that has a body dedicated to the UN Headquarters in New York. The International Committee for the Development of Lumbini was set in motion by U-Thant with Buddhist countries forming its membership. The Committee has been moribund for decades now, and the Nepal government is required to work with the UN to consider re-activating it to address all matters from preservation and archaeology, to landscaping, aesthetics and fund-raising.

How to ask for a reference for employment

Secretary-general Guterres will be interested to know that PM Dahal has just appointed a monk of dubious antecedents as head of the Lumbini Development Trust (LDT) which oversees both Lumbini and Kapilvastu, the hometown of Sakyamuni. A newspaper article described the LDT chief’s past in these words, as he took charge in August this year:

“He has earlier been charged with several crimes, including foreign employment fraud, possession of illegal firearms, accumulating property disproportionate to his known source of income, and possession of dual citizenship and passport.”

Murder commonplace, or malicious

It will be divulging no state secret in saying that Nepal has a prime minister whose party, having failed miserably in the first democratic elections of 1991, organised and went underground to wage insurrection against parliamentary democracy in 1996. Having caused enough mayhem over a decade of insurgency, the rebel leaders struck a deal to land right at the centre of parliamentary democracy. The so-called ‘people’s war’ was not waged against an autocratic royal regime, as believed by many foreign diplomats and even scholars. Meanwhile, the credit for the pluralism and democracy we enjoy today is thanks to the 1990 constitution, whose democratic foundations held firm even as the 2015 constitution was readied. The Maoist leaders’ own favoured document, which they tried to push through, resembled the constitution of North Korea.

The biggest flaw in the man who is the present head of government has been the enthusiastic promotion of extrajudicial killing of citizens, added to that his refusal till this day to express remorse or set the course for accountability for excesses committed, an exercise to rope in both insurgent and state-side perpetrators. After he came above ground, Dahal said in a live BBC Nepali Service interview that he had “personally issued a circular at the start of the insurgency instructing cadres to annihilate victims without first torturing them” – talk of admission of command responsibility.

This disdain for targeted victims is palpable in the Transitional Justice Bill that the government has submitted to parliament, drafted at PM Dahal’s behest by a turncoat human rights lawyer, which seeks to distinguish between ‘commonplace murder’ and ‘malicious murder’. Dahal’s flippancy regarding the lives of citizens was evident again in January 2020, when he told a gathering that he would take responsibility for 5,000 dead during the insurgency if others took responsibility for the remaining 12,000. There is a case being heard on this count against him by the Supreme Court.

From the start of the conflict, the Maoist leaders used child soldiers with abandon, but neither the international community nor the national polity seemed greatly bothered, then or now. The United Nations, on the other hand, should be, for it was UNMIN which certified the existence of the thousands of Maoist child soldiers, yet failed to find them a safe landing as it packed its bags and departed. It has been left to the former child soldiers to challenge the state establishment all alone, wanting to be counted, compensated and healed. PM Dahal’s personal effort, meanwhile, is to keep the reference to ‘child combatants’ out of the TJ Bill he submitted that is being worked on by a committee in parliament. His pressures on the committee members are intense.

OHCHR and UNMIN

The phalanx of UN specialised agencies and organisations have been active in Nepal for decades, from UNDP to FAO to WHO to UN Women, playing catalytic roles in so many arenas in a country that arrived late into open society and the ‘era of development’. Sadly, amidst all this, the society was diverted for a full decade by the internal conflict, with another decade devoted to the peace process and constitution-writing with their attendant political instability. That is when the two offices took centre stage, OHCHR and UNMIN.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) played an effective role during the conflict years. When Nepal’s transitional justice project is finally rescued from saboteur politicians bent on making it a faux process, OHCHR’s long-forgotten ‘Nepal Conflict Report’ (NCR) must be the main reference document, archiving as it does 30,000 papers on violation of international human rights law and international humanitarian law between February 1996 and November 2006. The concluding ‘core messages’ of the NCR to those meant to adopt and administer the Nepali transitional justice process are, in its own words:

Under international law, the Government of Nepal has a fundamental obligation to investigate and prosecute serious violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law that were committed during the conflict.

Where there is a reasonable basis for suspicion that a serious violation of international law occurred, these cases merit prompt and independent investigation by a full judicial process.

The transitional justice mechanisms are an important part of the transitional justice process but should complement criminal processes and not be an alternative to them.

All three prescriptions are being ignored blatantly by the national political parties old and new, and it is only the protests of conflict victims and rights defenders that have kept the politicians from buckling completely to Dahal’s desires and demands. Meanwhile, Western government and West-based INGOs that enthusiastically pushed Transitional Justice into the Nepali slipstream themselves have gone cold, a result of ‘TJ fatigue’ and newborn geopolitical calculations, it would seem.

The same person who headed OHCHR was assigned to lead UNMIN as the secretary-general’s Special Representative. This writer was among those who lobbied for his assignment to Nepal, knowing his earlier record. Incongruously, the gentleman’s tilt and tonality changed in the new position. Once a tussle for authority with the UNDP Resident Representative was resolved in favour of the Special Representative, there was a shift in UNMIN’s focus with a desire to privilege the Maoist party at the cost of the democratic parties – the very forces which had made way for the rebels in order to prevent the scorched earth policy that would have been implemented by the Army, which in 2005 was under the King’s direct command.

The Maoist supremo and his party thus received an unexpected boost and bonus from UNMIN as they entered open politics, and, critically, UNMIN also set the tone for how the Western officialdom and academia viewed the Nepali polity. That view was a caricature of Nepali society as static and ‘Brahminical’, with little recognition of the complexities of Nepali history and inter-community relations, or the attempts to usher transformation through representative democracy after 1990. The Maoist commandants were regarded as true leaders of the masses, out to deconstruct a feudal state rather than simply wanting to supplant the incumbents. The trajectory of the Maoist leadership of the past two decades has shown that the perception was faulty, but UNMIN is long disbanded.

The Maoist supremo and his party thus received an unexpected boost and bonus from UNMIN as they entered open politics, and, critically, UNMIN also set the tone for how the Western officialdom and academia viewed the Nepali polity. That view was a caricature of Nepali society as static and ‘Brahminical’, with little recognition of the complexities of Nepali history and inter-community relations, or the attempts to usher transformation through representative democracy after 1990. The Maoist commandants were regarded as true leaders of the masses, out to deconstruct a feudal state rather than simply wanting to supplant the incumbents. The trajectory of the Maoist leadership of the past two decades has shown that the perception was faulty, but UNMIN is long disbanded.

Whether it was ideological blinders at the top of UNMIN, an eye on a career ladder within the UN system, or simply activism gone wrong, the damage was done. Till today, much of how the Western world views the Nepali state establishment – and also why many ambassadors defer to Dahal as many do, beyond his position as prime minister– is defined by the bearing set by UNMIN and its first Special Representative. Without knowing what the Maoists did to rural Nepal in tandem with the security forces, there have been individual Western ambassadors that one can name who have been simply enamoured of Dahal and his ‘revolutionary’ tag.

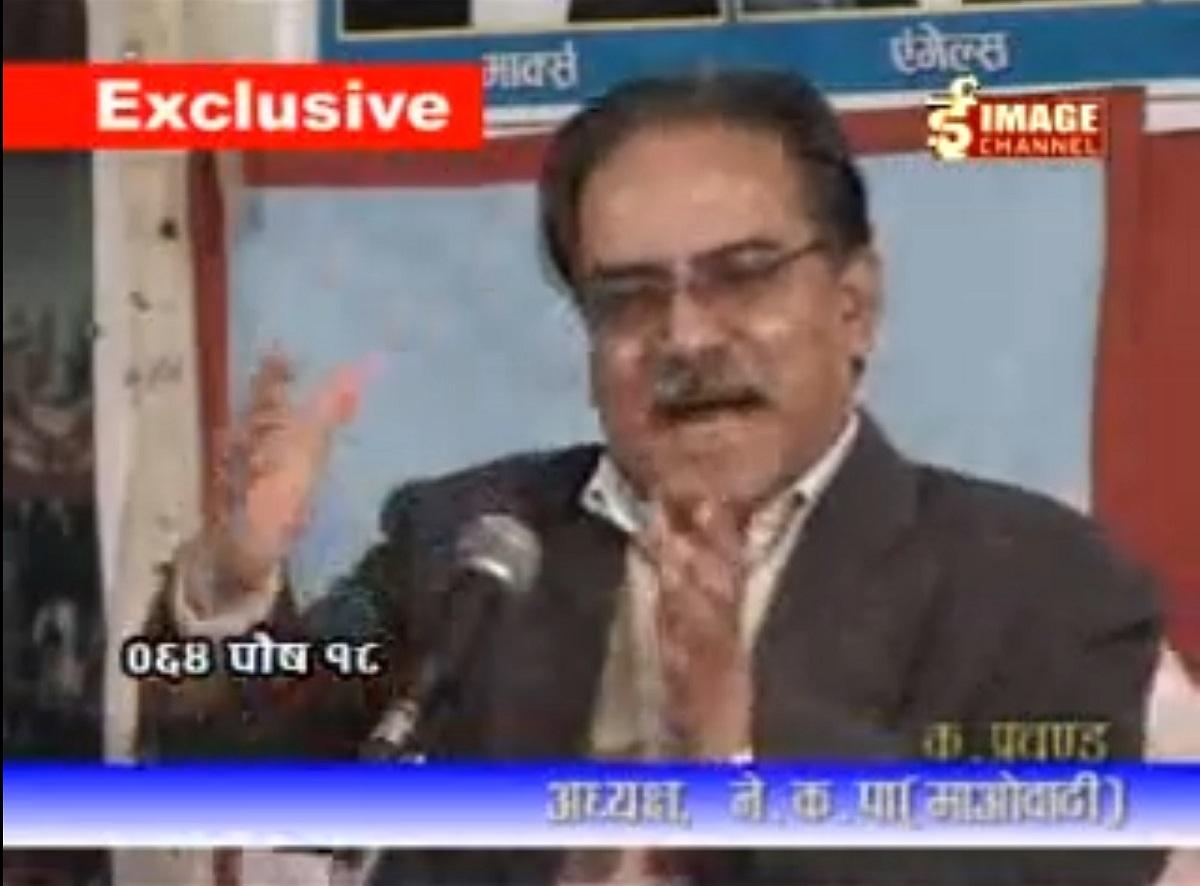

2009 video where Maoist Chair Dahal said he had fooled UNMIN

If UNMIN was biased, neither was it diligent. One episode will suffice to prove the point: In May 2009, a video was leaked where Dahal is mirthfully sharing with his cadre how the Maoist had outright bamboozled UNMIN as it was carrying out verification of combatants. Barely able to hold back laughter, Dahal said while the Maoists had no more than 7-8000 fighters, they had claimed 35,000, and got UNMIN to agree to 20,000. Keep in mind that UNMIN, with its well-paid experts on all matters from peace-making to mass psychology, advised the Nepali authorities to go into the 2008 elections with the inflated numbers of (armed) Maoists in the camps to prevent them ‘to go back to the jungle’. That is when the Maoists got their most votes ever, by blackmailing the public and getting a momentum that has lasted them till now.

Neither accounting nor accountability was sought of UNMIN, and it is indeed time to let bygones be bygones. But it would be a useful exercise for the UN’s peace-making and peace-building efforts if the secretary-general were to order a study of the Security Council reports of UNMIN to verify the alleged partiality.

A UN Alliance

The better the United Nations understands the Nepali reality and comes to its independent conclusions regarding the range of issues from transitional justice to human development and climate crisis, the easier it will be for the larger international community to come to a nuanced understanding of Nepal’s experience, and how to partner with it for global good. For its part, Nepal is presently buffeted by multi-sided polarisations involving China, India, the US and the West generally. It seems more impacted than other countries in the China-India periphery, perhaps due to its geographical positioning and landlocked nature. Within a suddenly fearsome international environment and shrill calls for joining this, that, or the other side – if there is a protective ‘alliance’ Nepal needs to join it is one with the United Nations.

Secretary-general Guterres and his team will surely use the upcoming visit to observe Nepal’s successes and assess its challenges. They will want to keep in mind that Nepal is not a ‘small’ country. It is regarded as such mainly because Nepal has land borders with two humongous neighbours and the size of its two other proximate neighbours, but Nepal is the 48th largest country by population among the UN’s membership of 193 nation-states. While Nepal seems to have been assigned the ‘basket case’ classification that earlier used to be the lot of Bangladesh, there are significant triumphs that are not propagated. Mark the fact that Nepal is the one large country of South Asia without the death penalty in law and practice, and it is the only country where the term ‘transitional justice’ is even uttered; each and every country has a history of long-term abuse of some part of the populace.

From Nepal, the international community could learn: how to adopt a constitution by elected constituent assembly unlike most experiences of appointed commissions; how to keep head above water amidst roiling and unrelenting international intervention over decades; how to prevent minority bashing and spread of inter-community conflagration within a Subcontinent that is becoming dangerously polarised by faith; and, how to keep borders open even as the trend elsewhere is to put up barbed wire and barricades. Nepal provides the neutral ground where all South Asians except Afghans are welcome with visa-on-arrival. Indians need merely ID cards, while Nepal as the headquarters of the SAARC organisation must consider removing the prior visa requirements for Afghanistan passport-holders.

Make no mistake, with all its flaws which include entrenched Kathmandu-centricism and historical marginalisation of mountain, hill and plain communities, Nepal is today (and thus far) the most open and democratic country in South Asia, one that is willing to experiment with innovations that are suggested. Nepal needs to preserve its pluralism and democracy for the sake of its own population most importantly, but also to hold a lamp to the rest of the subcontinent. It is therefore vital for UN officials to be alert to efforts underway to engineer constitutional collapse and a dismantling of democracy, if possible even a weakening of sovereign agency.

Despite a decade of violent conflict and political turmoil, Nepal managed to reduce infant and maternal mortality, making a success of community forestry, and being the only country in the Subcontinent where radio broadcasting remains open for true public broadcasting. The fact that it is about to emerge from an under-developed country to developing country status says something about successfully fighting the odds. On human development and hunger indices, Nepal is doing better than next-door Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, so there is little cause for the national embarrassment that is felt by so many. Meanwhile, Nepal is the sixth to seventh largest remittance-sending country to India, that too providing survival sustenance to the poorest parts in an arc from Eastern Uttar Pradesh to Odisha.

Transitional justice, climate crisis

To ensure that Nepal can finally end the peace process in a way that it does not have to suffer another conflict like in 1996-2006, Secretary-general Guterres’ United Nations should stand like a bastion in favour of a just end to the Transitional Justice process, particularly because those who introduced the concept themselves are no longer enthused. The Maoists, as well as lazy politicians and some commentators like to say flippantly that the process has to end “because it has gone on for too long”, as if one must do a hasty, shoddy process just to please the perpetrators.

If you ask the victims at large or their representatives, they are in a tearing rush to ensure reparation, but they do not want compromise on accountability for atrocities committed as we go in for truth and reconciliation. The victims do understand that if we do not have a TJ process that tackles emblematic cases of human rights excess under principles laid down by Supreme Court judgements and international law and practice, our society is doomed to a repetition of violent conflicts in the future. Similarly, if the issue of child soldiers is kept out of TJ’s purview, there will be more recruitment of underage citizens by extremists in future.

If you ask the victims at large or their representatives, they are in a tearing rush to ensure reparation, but they do not want compromise on accountability for atrocities committed as we go in for truth and reconciliation. The victims do understand that if we do not have a TJ process that tackles emblematic cases of human rights excess under principles laid down by Supreme Court judgements and international law and practice, our society is doomed to a repetition of violent conflicts in the future. Similarly, if the issue of child soldiers is kept out of TJ’s purview, there will be more recruitment of underage citizens by extremists in future.

The travesty that is the Transitional Justice bill placed by the Government before Parliament was fortunately noticed by four United Nations Special Rapporteurs, who wrote to the Nepal Government on 9 June 2023 severely critiquing the document and warning that Nepal was set to defy international humanitarian law. To specific queries sent by the Special Rapporteurs, the Prime Minister’s Office provided pro forma and inadequate answers, also hiding behind that fig leaf that the bill was now a ‘property of Parliament’.

It may take a few more years, but let us not rush the transitional justice process to please some Maoist leaders and select diplomats who may also see it as career enhancing. Nepali jurisprudence set by the Supreme Court already exists to push the ‘transitional justice’ process to its ethical conclusion, and no one should think of going outside those strictures. A principled rather than a fraudulently practical end to the TJ process would be a great gift to the long suffering victims of conflict. Properly watchdogging the process for false culminations, it would be a feather on the UN’s cap having safeguarded an important and exemplary process. Let future study tours from post-conflict societies visit Nepal as much as they do Colombia and South Africa.

With the Dahal government single-mindedly trying to foist an improper ending to the TJ process, and its other main focus being simply to survive in power, it has no desire or energy to have Nepal lead in any arena of international concern. Sadly, the climate crisis is one such area. The government does little beyond vacuously mouth global warming cliches, even as it cancelled a planned global climate summit titled ‘Sagarmatha Conclave’ as soon as it came to power.

Actionable Matters

As part of the globe’s ‘third pole’ (the Himalayas), Nepal serves as a veritable barometer of climate change, its populated terrain going from tropical to alpine within a span of less than a hundred miles. Because glacial retreat, reduction in groundwater and river flows, melting of permafrost and extreme weather events impact not only the Himalayas but the entire downstream biosphere, it is from Nepal’s populated mountains that the alarm bells will sound most credible and urgent.

It is the Nepali citizens themselves who must toil to keep their country democratic, inclusive, stable and progressing. The United Nations can assist, by reacquainting itself with Nepal, its foibles and successes. At an existential level, the UN needs to monitor Nepal’s sovereign agency even as geopolitical alliances seek to foist their agenda on Nepal, and the anti-minority sentiments to the north and south gallop threateningly ahead.

A truncated list of ‘actionable matters’ can be submitted to the UN Secretary-General, as follows:

A truncated list of ‘actionable matters’ can be submitted to the UN Secretary-General, as follows:

*Nepal’s security agencies get too few command responsibilities in UN peacekeeping operations for its long-standing participation and sizable contingent in a dozen theaters of operation. This is a matter where the good offices of the UN chief would be welcome.

*Within Nepal, the ‘clear and present danger’ that bears monitoring is the possible spread of ‘communal’ wildfires from the Ganga plain into Nepal, and the winter-spring of 2023-24 is a period that bears watching.

*Given that there are some who want Nepal to backslide by conjuring a collapse of the Constitution, the United Nations should be monitoring, and also side with those who suggest a sage and thorough review of a Constitution now in its eighth year.

*The life and livelihood of millions of its citizens toiling as labourers in difficult conditions in India, Malaysia, the Gulf and other countries is of vital concern for Nepal, also because it is their remittance that is helping keep the economy afloat. Their wellbeing should be a central part of Nepal’s development agenda, to be understood and also owned by the UN.

*Kathmandu Valley, Pokhara and other parts should be utilised by the United Nations for its international conclaves, given the open visa regime, the low cost of hospitality services and good air connectivity. This will support the economy while strengthening Nepal’s positioning within Asia.

*This very week, there is the election for the WHO’s regional head, with Nepal and Bangladesh competing. For the sake of the two billion plus population of the South- and Southeast Asia whose public health is the interest of the office in question, the secretary-general should use his good offices to ensure simply that the more qualified candidate is elected.

One hopes that UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ visit to Nepal will ensure that the United Nations team in Kathmandu, Geneva, New York and elsewhere are better equipped to observe Nepal and help it along in a rapidly despoiling international environment. But one might ask that all United Nations cars and jeeps revert to the ‘regular’ livery from before 1996, rather than remain the white behemoths with protruding antennae and ‘UN’ written in big blue letters. These ubiquitous vehicles subconsciously remind citizens that the conflict continues, whereas it is only Transitional Justice that needs to be properly brought to closure.