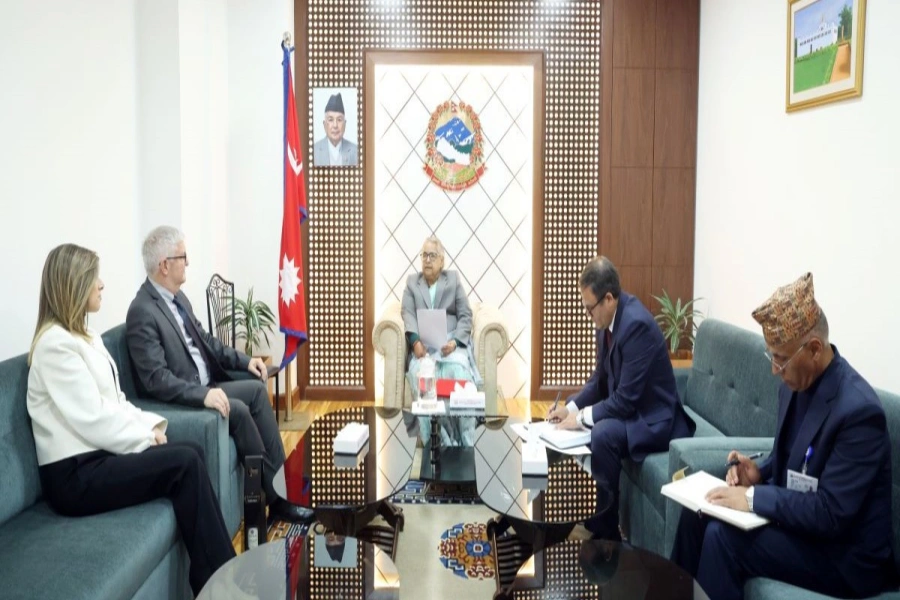

In a meeting with the government, they gave it straight. They expressed concerns about the competence of the government. They raised doubts about the ability of the government to allocate adequate resources to health, education and infrastructure. They pointed to persistent corruption, nepotism, and growing loss of government accountability.

To Nepalis who later learned about the meeting, only one question seemed to remain. What took the donors so long? Nepalis had figured out the poor state of governance a long time ago.

Donors, maybe most Nepalis as well, have always been a little reluctant to berate the government. If not government, who then? A much darker unknown lurked beneath. Government, however incompetent, is still all we have from descending into that unknown.

PHOTO: HORNBILLUNLEASHED.WORDPRESS.COM

Could the private sector, or businesses, provide a solution?

Businesses aren’t a particularly wholesome lot. They are greedy, selfish, ruthless, self-cantered, short-sighted and singularly driven by one thing—profits. But that’s also why we love them: for their singular ability to smell out the slightest waft of profit even from a basket of smelly rotten fish.

An interesting interplay between politics and the corporate sector is unfolding in India. It holds some lessons for us.

Twenty five Indian state-owned enterprises have accumulated approximately US $55 billion (Indian Rupees 3 lakh crores) in cash reserves from years of profits. That’s a staggering amount—almost 60 percent of India’s fiscal deficit in 2011-2012 and 20 percent of current foreign reserves.

These companies are not entirely state-owned. Coal India, for instance, which alone has about US $12 billion in cash reserves, is a publicly listed company where the Indian government holds 91 percent ownership. These companies are not purely private. But because they are listed on the stock exchange, they subscribe to the same set of corporate rules of disclosure, functioning and shareholder rights as other listed private entities.

The Indian government has been putting pressure on these companies to invest their surplus cash. Coal India has rolled out a US $7 billion investment program. SAIL (Steel Authority of India Limited) has announced an investment of US $24 billion for the next few years. Many other firms are launching similar short and medium term investment strategies.

The Indian government had the option of converting those cash surpluses into dividends and having it flow into the treasury. Instead, it opted not to spend those reserves on government programs. It has sought to channel them as investments into the economy. The Congress government’s electoral gambit is partly pegged on the speed and success of those investments.

Congress is likely to approach the 2014 general elections on a three-fold plank addressing the poor, reforms and economic growth. It will highlight the recently approved direct cash transfer to the poor, the world’s largest such scheme, to convince India’s poor that the government is working for them. It will showcase the hard fought victory on allowing foreign ownership in multi-brand retail to show that it continues to push for reforms. And it hopes that large investments led by state-owned enterprises will put some zest back into growth.

These investments by state owned enterprises are unlikely to immediately translate into growth, other than as a short-term burst. It is unclear if these enterprises even have the ability to deploy such large investments so rapidly in the first place. But all of that almost doesn’t matter.

The more important thing is the palpable sense that many large investments are being made or are about to be made. A critical threshold of this perception is enough to make everyone believe that the investment climate is now robust.

Economic growth can be reduced to an objective number. But it resonates little within the popular imagination. Investment climate, on the other hand, is a subjective measure based on perceptions. People vote based on these subjective perceptions; they feel hopeful or gloomy about their country based on these subjective perceptions. Governments draw legitimacy and public support from these subjective perceptions.

This is exactly what the Congress seeks. It needs those investments, or at least the possibility of those investments, to illustrate that India’s investment climate remains strong.

This unfolding Indian story is relevant to Nepal’s political distress.

Nepali businesses can provide a sense of stability. But first they need to articulate that business is continuing. On the fringes, producers are producing, traders are trading, consumers are buying, and the engine of growth is grinding away.

Nepali businesses must communicate that despite political risk of falling apart. Even as government falters, businesses continue to thrive in small but nevertheless highly significant pockets of productive activity.

While businesses cannot replace government, they can serve as a counter-weight by providing Nepalis an alternate source of stability. In time, businesses can even make the tasks of government more manageable by helping to shoulder the development load in more tangible ways.

This brings us right back to the beginning of this story—the meeting between donors and government.

For a long time donors in Nepal have experimented working with the private sector. There have been programs on reducing corruption, strengthening competition, enhancing capacity, banking reforms, and many others. But most of these have been short-lived programs designed to help meet a specific need.

Nepal’s continued political polarization and uncertainty now offers a great opportunity to seek an ambitious symbiosis between donors and the private sector—a symbiosis that not only results in economic growth, but offers meaningful development and leads to political stability.

This transition will not come easy. It will call on us to occasionally suspend belief, particularly long held ideological biases.

With governance collapsing, there is now a renewed emphasis on working with the private sector. But to succeed, donors must shed their wariness of hard-nosed, profit-motivated businesses. Businesses may be greedy, selfish, ruthless, self-centred, short-sighted, and singularly driven by profits. But if incentivized correctly, profits can also do amazing things. It can push development into the remotest corners and the least served groups in Nepal, and in a way that is far more enduring than any government could imagine. To make this engagement work, the self-righteous opposition to profit needs to be shed.

Development schemes partnering with businesses must be broadened, instead of focusing narrowly on bottom of the supply chain (rural infrastructure, agriculture, capacity building, micro-finance, and small and medium enterprises). They must work equally with large businesses as with small ones, equally in urban markets as in rural areas, equally across all communities. The entire system of business must be bolstered.

So far, private sector has been used mostly in the process of development without getting them to value development outcomes. That emphasis must change. Instead of getting businesses to see value in merely constructing school buildings, they must be incentivized to see value in educated children.

Get businesses to see profits in developmental outcomes, not just in the development process.

Is this even possible? I did warn you that this requires a suspension of belief.

The author is a consultant on energy and environment, and founded ReVera Information, a market research firm in New Delhi

bishal_thapa@hotmail.com

Provincial assembly member Sah to face suspension for polygamy