OR

More from Author

There is mismatch between Nepal’s commitment to communicable diseases and rapid spread of non-communicable diseases

In May this year, after his confirmation as the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus shared the organization’s priorities for the next five years. Universal health coverage (UHC) would be his main priority, he said, as well as three other issues: health emergencies; women, children and adolescent health; and health impacts of climate and environmental change. Hopefully, Dr Terdos can stay true to his words.

The UHC is the result of the third wave of global health and development initiatives. The first initiative was Health for All by 2000 (HFA by 2000, also known as Alma-Ata Declaration 1978), the second was Millennium Development Goals by 2015 (also known as the Millennium Declaration), and the third is sustainable development goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. The third goal of SDGs (‘Good health and well-being’) is primarily focused on health and wellbeing of all inhabitants of the planet, with the UHC as its ultimate objective.

The universal health coverage is provision of financial/social security in health and access to and utilisation of health services by the people who are in need of them. Historically, the concept of universal health care started in Germany back in 1970s, to be soon followed by the UK. Now most socialist and high-income countries have social security system in health or guaranteed health care for their citizens. Even in middle-income countries such as Indonesia, Mexico and Thailand have been making progress on their health and social security systems. However, there are many challenges to realize full financial protection in many developing countries, where the health system is weak or centralized and private sector dominates in tertiary health care.

What about us?

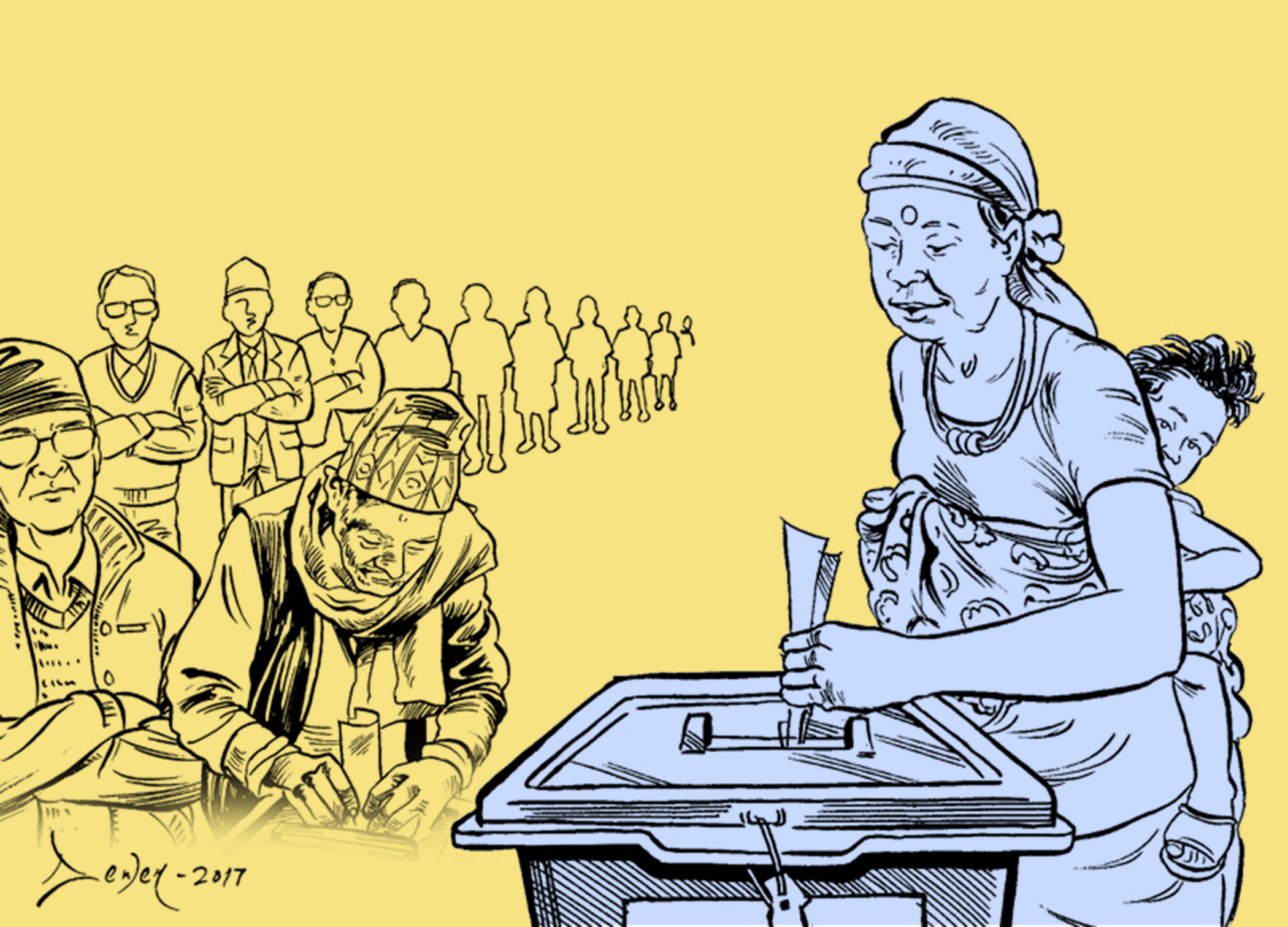

Nepali health care system is designed for prevention and protection from communicable diseases, maternal and child health, and nutrition. During the era of the HFA and MDG until 2015, all efforts were made to address these problems in children. In the global community, Nepal is known as having made remarkable progress in saving the lives of countless women and children. Despite this progress, inequality is a major challenge to reach the state of universal coverage in Nepal. There is good overall coverage of interventions like child immunization, institutional delivery, and family planning, but overall, health disparities are increasing between privileged and disadvantaged groups.

Unavailability of skilled manpower, lack of even basic medicines and management problems continue to plague our health care system.

There is also a mismatch between Nepal’s old commitment to communicable diseases and the fact that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) were responsible for 60 percent of global mortality in 2015. The injuries related to road accidents and national disasters are leading to loss of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) in Nepal. Besides this, there has also been a significant increase in lifestyle diseases like hypertension and diabetes. These ‘rich man’s diseases’ are now common in Nepal as well. Yet our health care system is uniquely unprepared to handle these NCDs.

Moreover, people from remote areas have poor access to medical emergencies like assisted delivery (for example C-section) though the government has committed to provide these services for free. The preventive measures for NCDs are inadequately incorporated in our health policies and strategies. Although sporadic measures like provision of Package of Essential NCDs (PEN), screenings for kidney diseases and procurement of medicines have been initiated, a systematic approach is still missing.

Most Nepalis also have poor access to tertiary health care services because of our centralized public hospitals. Tertiary curative services are only available in zonal and private hospitals. People of remote areas neither have access to, nor can they afford, those services that are only available in big cities. There are teaching hospitals in some regions, but the quality of the services offered by these hospitals is a suspect because of their poor infrastructure, lack of equipment, and acute shortage of faculties in their clinical departments. People’s trust in such medical establishments is thus low.

All in all, Nepal has four major constraints to achieving universal coverage: first, inequitable coverage of routine health services; second, lack of attention on NCDs and injuries/trauma; third, unaffordable, urban centered and unregulated private services; and fourth, inadequate and lopsided geographical distribution of public hospitals, a problem that is further compounded by their lack of capital and human resources. Additionally, our public hospitals have been badly politicized and have become hotbeds of corruption.

Every Nepali citizen has a constitutional right of universal access to health services.

Nepal needs to get serious about implementing this constitutional provision and honoring its international commitment to universal care. As the country is in the process of finalizing its federal setup, it is also the right time for radical reform of our public health care system.

There should be provision of hospitals in each local structure (rural municipality) that is headed by a medical generalist (MDGP). This will increase people’s access to curative services at the local level. Moreover, the government needs to regulate private hospitals/providers and standardize their services with regards to quality and cost.

Another crucial area of reform is provision of universal health insurance, which is vital in a poor country like Nepal. All these steps will help us get closer to realizing the ultimate goal of universal health coverage.

The author is a PhD student in ‘health system and policy’ at University of Queensland, Australia

Twitter: @resham_khatri

You May Like This

Mugu's health post operating without health workers

MUGU, Jan 10: Absence of health workers at a local health post of western Khatyad Rural Municipality-10, Hyanglung of Mugu has... Read More...

Ministry of Health suspends 18 health workers for obstructing Polio vaccine program

KATHMANDU, March 5: Ministry of Health on Sunday suspended 18 health workers, including three district health office chiefs, on the... Read More...

Prez Bhandari summons Health Minister, inquires about Dr KC’s health

KATHMANDU, July 20: President Bidya Devi Bhandari has taken stock of the health condition of Dr Govinda KC who is... Read More...

Just In

- Youth attempts suicide amid police torture over Facebook comments against home minister

- Time to declare EVMs’ end

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

Leave A Comment