Relocating NRB away from Kathmandu will be crucial in ushering many transformative changes in Nepali economy. It will help keep politics and finance separate from each other

Location matters. As a means to an end of greater financial inclusion and central bank autonomy, I would like to propose the idea of a change of address for the central bank of Nepal. Though the notion is seemingly simple, its potential for transforming the financial landscape of Nepal is radical. Our constitution advocates for federalism in at least three dimensions—political, fiscal, and financial power. Of the three, political and fiscal federalism have been implemented whereas financial federalism has been in total disarray so far.

Kathmandu has been both the political and financial capital of Nepal. It emerged as the modern financial capital when Nepal Bank Limited was established in 1938. Establishment of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) as the central bank of the country in 1956 further reinforced Kathmandu as the financial capital as economic activities and financial resources were concentrated in and around its place of establishment. Kathmandu’s share of total deposit is 68 percent and loans nearly 50 percent according to NRB Report 2019. Another reason for the over-congestion in Kathmandu is that most banks and financial institutions (both public and private) have their headquarters in Kathmandu. Many a times, the political process and financial sector get entangled, hindering the dynamic growth of the latter. To improve efficiency, politics and finance need to be kept at an arm’s length distance from each other. This is why political and financial capital of Nepal should be in separate places.

Measures that failed

Some initiatives had been taken toward this end in the past. The government, including NRB, initiated some good reforms to reduce financial concentration in Kathmandu. The first was the mandatory productive sector credit requirement of 25 percent under which banks were asked to provide credit to certain priority sectors including agriculture. It was completely phased out nearly 15 years ago, and reintroduced since 2010. Such intermittent policy has not been successful in attaining the goal of financial decentralization.

Revised interest rate corridor system introduced

The second measure was deprived sector lending requirement. Under this scheme, banks are required to provide directly or indirectly at least five percent of their loan portfolio to weaker sections of the society. As of May 2019, banks had provided Rs 171 billion to the deprived sectors. Even though this has helped divert resources from urban to rural Nepal, it has not taken place on a significant scale.

Introduction of the concept of regional commercial banks in 1996 was another reform measure. The private sector was encouraged to establish regional commercial banks with lower paid up capital. Under this policy, there were six commercial banks established outside the valley till 2012. Now all these commercial banks have shifted their headquarters to Kathmandu leading to further concentration of financial resource in Kathmandu. The government had also introduced the policy of allowing private sector to establish development banks and finance companies with the lower level of paid up capital than that of commercial banks. The objective was to encourage the private sector to establish development banks and finance companies outside the valley through the lower level of capital requirement. As a result, 71 of 88 development banks were operating exclusively outside the valley before 2012. Now, due to the merger and acquisition policy and the hike in paid up capital, the number of development banks operating exclusively outside the valley has come down below 22.

Then there was the policy of allowing financial NGOs to conduct limited banking transactions under the Financial Intermediaries Act (1998). However, NRB has derecognized them since 2014. These initiatives did not help to lessen the financial concentration in Kathmandu.

Shifting NRB

One of ways of reducing financial concentration would be relocating NRB away from Kathmandu, somewhere in Chitwan-Nawalpur area. The location has a strategic advantage of being not only an emerging area, but also the central point in mapping of Nepal. This policy step, if implemented, will be crucial in ushering many transformative changes in the Nepali economy.

First, a change of location will help keep politics and finance separate from each other, thus reinforcing central bank independence to some extent. Keeping arm’s length relation with the government is crucial for maintaining central bank’s independence. If we look at South Asia, India and Pakistan have adopted this practice of locating the central bank in a financial capital distinct from its political one. Second, it will help reduce financial congestion as some banks and financial institutions will move away from Kathmandu to where NRB gets relocated.

Third, it will help promote financial inclusion because banks and financial institutions will be motivated to move way to other parts of the country. As per the World Bank’s report, while the size of adult population with financial access is relatively small at 45 percent in Nepal compared to 80 percent in India, the size of informal economy stands at 37 percent of GDP. Given this context, promoting financial inclusion is important for augmenting lendable resources to help ease credit-crunch-like situation currently facing the country as well as for improving the effectiveness of monetary policy.

Fourth, relocating NRB away from Kathmandu will also help prevent further decimation of development banks and finance companies. Once NRB is relocated away from Kathmandu, development banks and finance companies will have no inhibition in operating outside the valley. Development banks and finance companies are serving the economy in their own ways. For example, while development banks are for financing small and medium sized enterprises, finance companies are meant for consumer financing.

Holistic approach

There is a greater need to initiate structural reforms aimed at decentralizing financial resources for preventing the likely discontentment arising from subnational governments in the near future. Acceleration in decimation of banks and financial institutions is likely to create a sense of loss of ownership among people and regions. If people perceive this loss to be due to the active pursuit of mega merger by policy makers, there will be a greater hostility against the state. For college graduates, only hope for getting jobs is the financial sector. If large scale merger leads to job losses, people will have pessimistic expectations about Nepal’s economy.

A financial vacuum like situation created by the policy of financial consolidation of large scale mergers will compel provincial governments to set up development banks of their own. In that case, NRB will have a tough time independently regulating and supervising such banks, risking financial stability going forward. Therefore, policy makers should rekindle hope, not despair, and their policies should be holistic in nature, not eccentric.

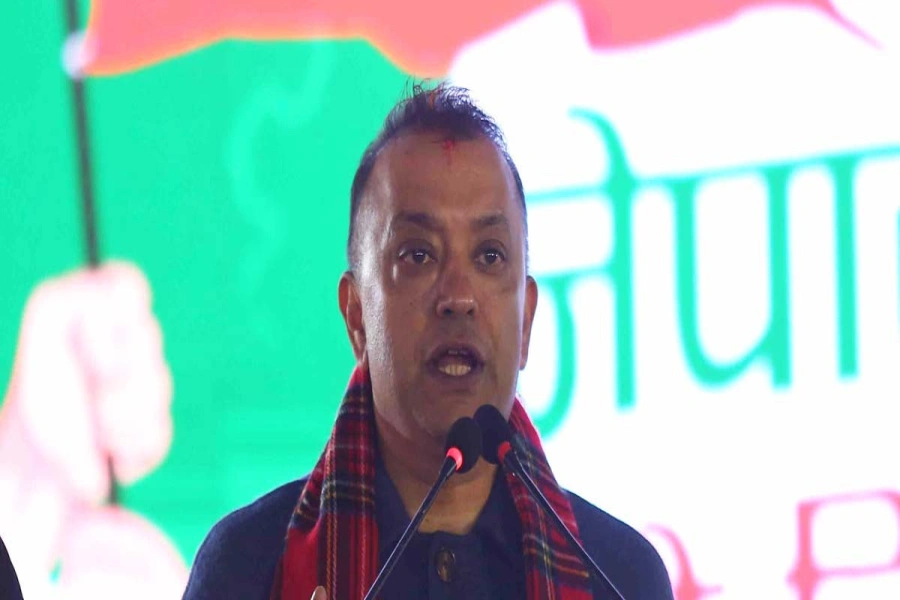

The author is Former Executive Director of Nepal Rastra Bank