The recent Gen-Z revolt has shown the public’s frustration and anger towards the political system, with its corrupt leadership and dysfunctional government structures.

But the revolt has so far failed to change the system itself and its corrupt institutions, such as the transitional justice bodies and constitutional commissions. These state-led justice bodies have excluded and marginalised the general public and victims, denying them the space to claim their rights.

Those of us who have been fighting for the rights of conflict victims see this clearly. We see authorities who ignore the most vulnerable, and indeed an entire citizenry for whom they have nothing but contempt. The state’s response to the Gen-Z revolt is yet another sign of how far those in power will go to retain the upper hand.

Conflict victims have suffered for decades from such attitudes and from institutions like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP). Both bodies have further violated our rights even as they pretend to operate in our names.

Despite such obstacles, we must continue to speak truth to power. The old approach to justice is losing credibility, and in its wake a new system will be born. The seeds of change are germinating. Conflict victims and Gen-Z members are waking up and raising their collective voice for transformative change.

New revolution possible: Baidya

We should resist the old corrupt system, which has rejected victim-centred transitional justice (TJ). The two existing commissions were politically driven and appointed by the former government. They have lost all credibility and have been boycotted by victims and survivors from the moment they were established.

On 21 November, the 19th anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA), representatives of victim groups organised a sit-in protest at the TRC and CIEDP, demanding the resignation of the commissioners. If they do not resign immediately, the situation will escalate.

The peace process, of course, is incomplete. Indeed, the transitional justice process itself was flawed. It was state-centred and dominated by people who were directly involved in past crimes and who have since derailed the justice process. The TJ system failed to provide space for victims and survivors in practice. The politically led, highly centralised TJ process even excluded the role of victim movements, grassroots activism and meaningful victim participation—elements essential for change and delivery.

An ethic of care and solidarity within victim movements has been the basis for mobilisation and a key element of locally led TJ. Solidarity and activism challenge isolation and build psychosocial resilience. Victims and survivors have transformed themselves into social leaders and agents of transformative change, redefining what it means to be a victim. This new victim identity transcends politics and provides a positive example of community reconciliation. Without the active role, participation and cooperation of victims, the ongoing stagnation of the state-led TJ process may deepen, and victims will suffer further without outcomes. None of the actors in TJ can ignore the transformative potential of victims’ participation, which demands a genuinely victim-led TJ process.

How the CPA Failed from the Perspective of Victims

Victims and survivors were not part of the CPA. The process was led by elites and driven by powerful actors, both national and international. It did not include victims in discussions or decision-making about justice. External actors were concerned primarily with constitution building, peacebuilding and elections at the top. This created a major obstacle to mobilising survivors at the community level. It also detached justice from the broader peace agenda.

Although the CPA called for victim participation, victims and survivors have been continually excluded from the peace process, despite all the work they have done on the ground. Their demands for consultation have been ignored. Instead, corrupt political elites and alleged perpetrators have dominated the transition, making only superficial changes while keeping structural impunity, violence and marginalisation intact. Justice, truth and sustainable peace remain ideals, not realities.

Following the CPA, Nepal became a federal republic and declared a secular and inclusive governing system. However, the traditional structures of the bureaucracy, security forces and courts remained intact. The lack of structural change and the continued domination of political elites have led to widespread abuse of power and public resources, as well as the entrenchment of corruption and impunity.

At the same time, these political elites have undermined transitional justice at every turn. Their leadership has sparked widespread anger among conflict victims and the general public, as demonstrated by the recent Gen-Z revolt.

Looking Forward – Create a Victim-Centred Justice System or Face a New Revolt

This moment shows us that all demands for justice are interconnected.

Transitional justice will be incomplete without justice for those killed in September, just as justice more broadly will remain incomplete until the long-term interests of Nepalis take precedence over the short-term corruption of elites.

The new government should work with victims and survivors of the previous armed conflict, as well as the new generation of Gen-Z conflict victims, to transform the justice process. The TJ commissions should be dismantled; otherwise, they risk facing serious backlash at the community level. They have already failed to win public trust and have lost credibility among survivors and victims.

We need a new deal. We need a model of justice, centred around victims, that inspires trust and hope. This presents the new government with a genuine opportunity to pursue transformative transitional justice and build a partnership with civil society based on trust.

Such a new deal would create wider space for transformative political change and address the expectations of all Nepal’s victims and survivors, including Gen-Z. It would also offer the best hope of avoiding another cycle of violations and revolt.

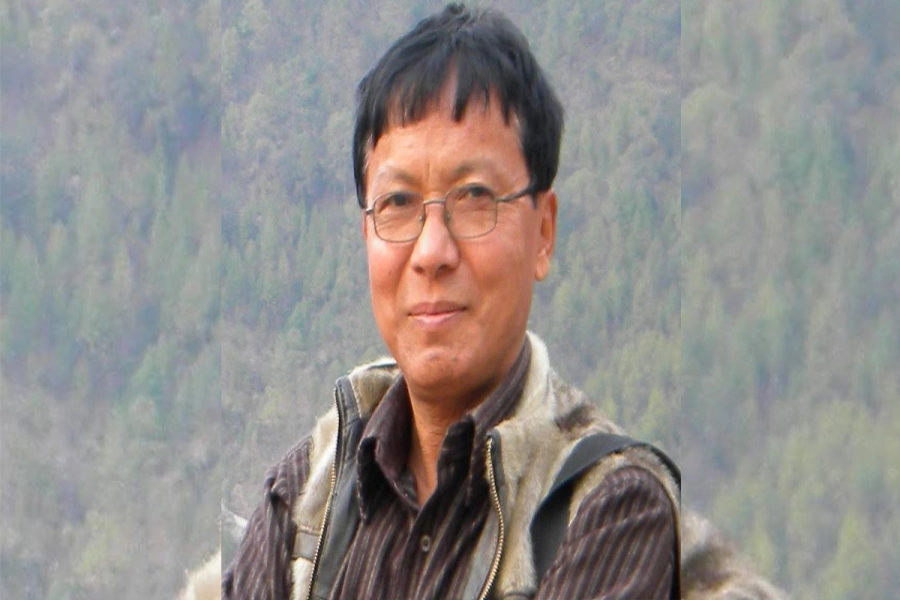

The author is a victims’ rights activist and Chair of the National Network of Victims and Survivors of Serious Human Rights Abuses. His father was forcibly disappeared by the State in 2001.