The violence in Dailekh shattered the uneasy calm that had hung over Nepal. Opposition parties are determined to carry through with their protests. The government is equally determined to brave the onslaught. Fringe parties are sharpening their bayonets on the sidelines.

The spectre of civil conflict suddenly looms ominously over the horizon.[break]

Of course, conflict should be avoided. More importantly, conflict can be avoided. Inspiration for a solution comes from an unlikely source—a jail cell in Hyderabad where Jagan Mohan Reddy has been held since May 2011.

Nepal’s political establishment should learn from Jagan Mohan Reddy. The Indian Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) arrested him last summer in a disproportionate asset case. He has been in prison ever since. His bail plea was struck down again this month.

PHOTO: NEPALEVERESTNEWS.COM

Jagan Mohan is the son of Y. S. Rajasekhara Reddy (or YSR more popularly), the late two-time Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh. YSR died in a helicopter crash in September 2009 while in office.

Jagan Mohan is charged with having illegally acquired significant wealth through a pattern of systematic corruption in the state. P Shankar Rao, a former minister in the state, alleged that Jagan Mohan’s assets grew from Indian Rupees (INR) 1.1 million to INR 430 billion since his father took office in 2004. The Enforcement Directorate has already attached INR 1.4 billion of Jagan Mohan’s immovable property and movable assets.

CBI launched investigations into Jagan Mohan’s assets in 2011, shortly after he split from the Congress to form his own party, YSR Congress. He denies all of the charges, claiming that the investigations are a politically motivated campaign to smear YSR’s legacy and punish him for his defiance.

There is little doubt that Jagan Mohan is no saint. YSR built a political network of patronage to emerge as a bastion of Congress strength in the South – a network he exploited successfully to claim an odds-defying victory in the 2009 assembly elections. Jagan Mohan rode his father’s network to dizzying heights of commercial success.

But that’s not what Nepali politicians should learn from Jagan Mohan. The lesson for Nepal is what he does next, after his father died.

A few months after YSR’s death, Sonia Gandhi, the Congress President, made it clear that she would not endorse Jagan Mohan’s claim to the Chief Minister’s post. Unable to challenge the Congress party in legislature, he decided to take his claim directly to the people. But he lacked YSR’s political credibility. He was a relative political novice, still lacking his father charisma and gravitas.

A part of his father’s political machinery remained loyal to Jagan Mohan. But that would not have been enough to take on the might of the Congress in Andhra. So, he did something clever—he hijacked his father’s legacy before the Congress could lay claim to it.

“Almost 660 people have sacrificed their lives for my father. Some of them committed suicide. I am telling all of them that the great leader YSR is not dead, he lives inside us through his ideals,” he said in an interview to Caravan magazine in May 2012.

Six months after his father’s death, Jagan Mohan launched the Odarpu Yatra [consolation tour], though Congress had expressly forbidden him to do so. The journey took him 1,500 km across the state, into 300 villages and more than a dozen districts. Along the way he unveiled some 450 statues of YSR and sharpened his stump speech around the memory of his father.

In the 2012 by-elections in the state, Jagan Mohan’s party won 16 of 19 seats. Congress, which had held 15 of those seats, took the brunt of the loss, even forfeiting their deposits in four constituencies. Jagan Mohan won his own seat by a record margin, though he was already in jail by then.

Jagan Mohan has emerged as a new power centre in Andhra’s politics. He offers little more than his father’s memory; his father’s legacy is his political base. He is still at an early stage of his political career and his future success will depend significantly on how he continues the narrative of his father’s history.

Such personalized historical narratives are important. Rahul Gandhi, for instance, used it to great effect in the recent Chintan Shivir where he was formally promoted to number two in the Congress party. In a speech at the end of the session, he evoked the images of his great grandfather, his grandmother and his father.

It was a speech rich in irony. Rahul Gandhi said his vision was to challenge the concentration of power so that all of India could be empowered. He was himself the very product of that concentration of power. But none of that irony mattered. In an emotional speech, he described how his mother had come to his room the previous night and cried, saying “power is poison.”

Rahul Gandhi’s narrative of the sacrifice from his family and his willingness to follow in the footsteps of his ancestors, knowing fully well the dangers of power as poison, was enough to seal his position as the undisputed leader of the Congress party. It was enough to move the audience to tears.

Nepal’s history, on the other hand, has been erased; if not totally erased, at least smudged beyond recognition. The current political crisis is as much about the absence of history as it is a crisis of leadership.

The contemporary history of Nepal now starts with the Maoist movement. The narrative is of a rag-tag group of insurgents, guided along by Prachanda Path, that ultimately coalesce into a force strong enough to defeat monarchy, Hinduism, a decayed democracy, and institute a new secular Republic.

The success of the Maoist movement has been largely attributed to the power of their armed struggle and their message of change. This is only partially true. Their success also comes from the deconstruction of history. They reduced the monarchy to a bunch of blood-sucking selfish scoundrels, Hinduism to an evil design for social exclusion, and other political parties to, well, a group of weak hearted turncoats that would jump at the first instance of opportunity.

The Maoists erased history. It now starts with the liberation they offered.

Opposition parties need to reassert a history of their own. They need a narrative to show that Nepal’s awakening began not with the Maoist movement but with BP Koirala and others before and after him—early rebels who hijacked planes, blew up bridges, lived in exile, took bullets and made sacrifices. Nepal’s empowerment, and the success of the Maoist movement itself, must appear as a continuation of that process.

Opposition parties need a historical narrative that promises equality and prosperity for all.

It may be tempting for the opposition parties to match the Maoist government eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. But rather than resort to violence, opposition parties should fight with the strongest weapon they have: the legacy of their struggle for Nepal.

Somebody please dust off a picture frame of BP and hang it up for the whole country to see.

The author is a consultant on energy and environment

bishal_thapa@hotmail.com

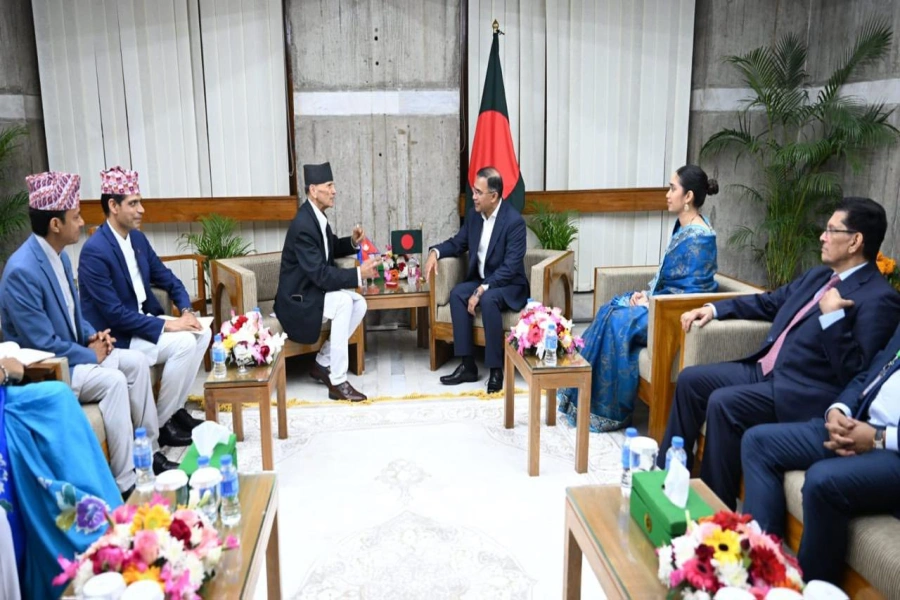

EPG univocal on amendment, rewriting, review of 1950 Treaty