OR

Bhairab Raj Kaini

Bhairab Raj Kaini, columnist for Republica for the last ten years, is an agriculture expert with experience of forty years in the field.bhairabr@gmail.com

More from Author

Agriculture is being feminized in Nepal following the rapid exodus of men

In recent times more and more women have involved themselves in agriculture. Women’s participation in agriculture labor force in Nepal had increased from 36 percent in 1981 to 45 percent in 1991 and, by 2016, it had reached over 50 percent. Globally, women make up 45 percent of agricultural workforce—rising to 60 percent in parts of Africa and Asia—even though they own less than 20 percent of agricultural land, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

This suggests that agriculture is being feminized. In the Nepali context, this is mainly due to the decade-long armed conflict and poverty which resulted in high out-migration of rural men in search of lucrative jobs. In fact, women are now main producers of food and livestock and they also help with natural resources and bio-diversity conservation.

Because of their multiple roles, they have greatly contributed to overcoming household food insecurity.

Integration of crops, livestock and forestry are characteristic features of Nepali agriculture in all three of its ecological regions. In farming, men and women work together, even though women’s involvement in farming activities varies with location, season, crop type, and on livestock and socio-economic features of households. Women’s involvement is higher in our hills and mountains compared to the plains. Women’s involvement in farming also varies with land-holding size. The larger the size, the lesser the involvement of women in farming activities. Also, the share of women labor force is higher in vegetable production than in fruit production.

Many studies indicate that women work longer hours and have greater workloads compared to men. On a daily average, a Nepali woman works three hours longer than does a man. Among the three ecological regions, women of hills and mountains work longer as compared to women of plains.

Despite women’s increasing role in agriculture, traditional social norms and laws that are biased in favor of men act as barriers to women’s equitable access to productive resources. Most agricultural lands are still under the control of men due to the traditional Hindu law of succession, whereby male offspring are entitled all the parental property including land. Though the new Land Act provides daughter-in-law and unmarried daughters under 35 the same rights, this has not been fully practiced yet.

Another important agricultural resource is water. Since water is very much linked with land, activities related to irrigation are exclusively under men’s domain. Hence there is negligible participation of women in water users’ groups formed by the Department of Irrigation.

The other interesting thing is that although women are more involved in caring of farm animals then men, men make major decisions on buying and selling of livestock.

However, the decision- making power on livestock also depends on social, ethnic, regional and economic status of farm households. Women of Janjatis backgrounds have more control over livestock as compared to Brahmin/Chettri, Maithali and Madheshi women.

Our society believes that women are poor in marketing and mathematical calculations and so do not have the ability of bargain. Such perceptions limit women’s access in marketing of agricultural products. Since access to marketing is directly linked with income, women are mostly deprived of this income-earning opportunity. However, a significant number of women traders are seen in vegetable markets of Kathmandu these days.

Credit, farm machinery and tools, and technology are also essential inputs in agriculture. Although women’s labor inputs in farming are often greater than men’s, they rarely have access to these inputs. So far as access to extension services and trainings are concerned, there is an overwhelming domination of men. Women’s access to extension services is also limited due to inadequate number of women extension workers. Similarly, women have limited access to institutional credit and other production inputs. The Nepal Agricultural Research Council’s (NARC) research activities also ignore women.

As we are yet to come up with women-friendly agricultural policy, there is big gap in daily wages in agriculture between men and women.

Although it has been many decades since we understood women’s crucial role in food production and security, the Ministry of Agriculture (MOAD) has failed to establish gender units and focal points in its different departments. Instead the Women Development Division of the MOAD has recently been degraded to a ‘section’. As a result, women’s needs, perspectives and knowledge are not sufficiently considered in development of its policies and programs.

There is a worldwide realization that if women farmers are given the same access to land, tools and credit as men, the resultant increase in food production would dramatically reduce world hunger. According to Neven Mimica, the European Union Commissioner for International Cooperation and Development, agricultural yields would increase by almost a third if women had the same access to resources as men.

A number of initiatives, such as secure land tenure, greater financial inclusion and greater access to technology, extension services and trainings, as well as to information and markets, are essential to make our agriculture gender-smart.

Women candidates should be encouraged to study agriculture and to join as Junior Technicians (JTs) and Junior Technical Assistants (JTAs) and given women’s poor mobility, more short trainings should be organized at the field levels. Skills trainings should include functional literacy programs that enable women farmers to develop reading, writing, calculating, speaking, and listening skills, while they also acquire vital knowledge on agriculture.

Likewise, there should be greater emphasis on women entrepreneurship through trainings.

This should go hand in hand with allocating certain decision-making posts in agricultural services to women. Lastly, the new land use policy need to be urgently implemented so as to ensure equal land rights of men and women.

bharabr@gmail.com

You May Like This

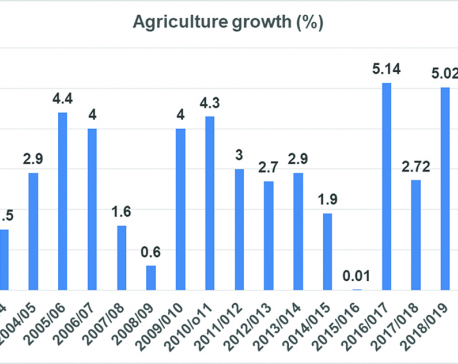

Erratic pattern

Agriculture in Nepal is suffering from years of under-investment, limited research, scant inputs and lack of technology and services for... Read More...

Agriculture Knowledge Centre established

SAPTARI, Oct. 4: An Agriculture Knowledge Centre has been established in Rajbiraj district by the Ministry of Land Management, Agriculture... Read More...

All activities of Agriculture and Forestry University, Rampur, halted

RATNANAGAR (Chitwan), August 7: All activities of Agriculture and Forestry University, Rampur, have been halted for the past one week... Read More...

Just In

- CM Kandel requests Finance Minister Pun to put Karnali province in priority in upcoming budget

- Australia reduces TR visa age limit and duration as it implements stricter regulations for foreign students

- Govt aims to surpass Rs 10 trillion GDP mark in next five years

- Govt appoints 77 Liaison Officers for mountain climbing management for spring season

- EC decides to permit public vehicles to operate freely on day of by-election

- Fugitive arrested after 26 years

- Indian Potash Ltd secures contract to bring 30,000 tons of urea within 107 days

- CAN adds four players to squad for T20 series against West Indies 'A'

Leave A Comment