OR

Book Review

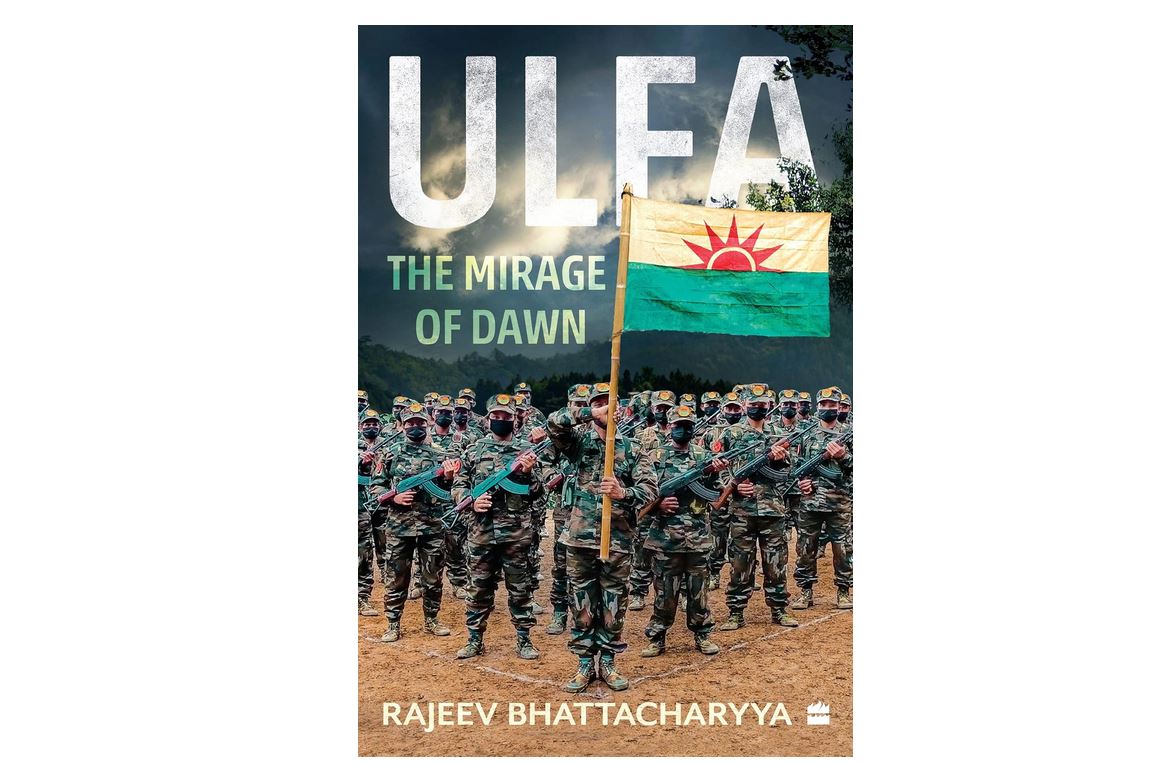

'ULFA: The Mirage of Dawn’ offers a remarkably balanced narration on history of ULFA

Published On: January 27, 2024 03:34 PM NPT By: Rajesh Singh

Rajeev Bhattacharyya’s book offers a remarkable history of ULFA, its formation and rise to prominence, the interplay of its principal characters, the role of foreign elements and wane in its influence

The country, and particularly the Northeast, has had reason to cheer after a faction of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) led by insurgent leader Arabinda Rajkhowa recently signed a peace agreement with the Assam government and the union government. The breakthrough came after more than a decade-long negotiation between the various stakeholders, and an even longer period of violence that claimed many lives and disrupted normalcy in Assam, whose repercussions were felt in the rest of the northeastern region as well. Commendable as it is, the deal, we must remember, is incomplete so long as the other, equally important faction led by Paresh Baruah, comes to the negotiating table and an accord is arrived at with this faction as well.

Experts understand very well the complications that are strewn in the path of an agreement—a road that is full of metaphorical landmines—and are therefore relieved at the progress made so far. Indians by and large are perhaps unaware of these complexities, and they would gain immensely from perusing the book, ULFA: The Mirage of Dawn, by Rajeev Bhattacharyya. The author brings to the narrative his long experience in covering ULFA, the unique insights he has gathered along the way, the many interviews that he conducted with the leaders of the outfit (often away from the public glare and in their hideouts that were out of hounds for outsiders). Bhattacharyya’s book offers a remarkable history of ULFA, its formation and rise to prominence, the interplay of its principal characters, the role of foreign elements and wane in its influence.

A proper understanding of a separatist movement must begin with the causes of the movement’s formation and the manner in which those causes were dealt with by officials from time to time. Such an understanding is not meant to provide a cover or a justification for the violence unleashed by the insurgent outfits, but to gain a handle over the root of the trouble. Negotiations succeed when a certain level of give-and-take is achieved, and when leaders from all sides accept and acknowledge the ground realities. Bhattacharyya, equipped with a first-hand understanding of the issues, provides a narration that is remarkably balanced. Indeed, the outstanding merit of the book is that it does not fall into the trap of sermonising, but presents facts in a clinical fashion. In this approach, he manages to, without having to over-exert himself, offer tips and ideas for the way forward.

The author gives extensive details on how the ULFA cadre, beginning with its senior leaders, received training in arms and guerrilla warfare on Myanmarese soil. But before that, the organisation faced several hurdles. Its intentions were not initially trusted by its would-be patrons; it did not have enough money to purchase arms and ammunition—in fact, its leaders faced challenges in even arranging money for travels across the border for training purposes. ULFA managed to solve the money problem off and on by targeting private and government assets, and when they attacked armed Indian personnel, they carted away firearms as well. But it is not just Myanmar that ULFA tapped; according to the author, there were strong linkages with Pakistan and Nepal as well.

Bhattacharyya also, and rightly, dwells on the responses of the governments over the decades. The mid-eighties, which saw the replacement of the Congress government that had completely failed to tackle the insurgency) with that of the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), was an especially challenging one for the state. ULFA stepped up its activities with a series of targeted killings—just a day after the swearing-in of the new government, a senior police official was gunned down, and a day later a leading journalist was shot. To make matters worse, ethnic clashes too broke out during those days, rendering the new government in a state of helplessness. This only helped ULFA, and, given the emotional appeal on which it ran the campaign, the separatist body continued to receive tacit and direct support from a good section of the public, thus making the government’s task even more difficult.

The author correctly points out that the bloody campaign launched by ULFA over the decades resulted in few tangible gains for the separatist outfit. The dream of a ‘sovereign Assam’ remains just that—a dream, and it is unlikely to be ever realised. Perhaps it is this realisation of the futility of continuing with a movement that has no chance of realising its original goal that made the Rajkhowa faction to see reason and enter into a pact with the government. In fact, over the past few years, ULFA has also lost the support of the people of Assam. In 2022, the government felt confident enough to lift the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act from some regions of the state.

What remains to be seen is, if and when Paresh Baruah comes to the table. The anti-talks group can continue to be relatively safe so long as it remains a resident of Myanmar. But that is hardly an achievement for which ULFA has been fighting. Meanwhile, the author flags a very real danger: that of its leaders, who are still on the run, establishing and strengthening their links with terrorist groups of various hues operating out of Pakistan and Bangladesh. As he notes: ‘…the possibility of radical Islamist organizations gaining prominence in the country (Bangladesh) cannot be ruled out, in which case there could be disturbances in Assam and other border states in India.’ The observation gains added pertinence given that elections are due in Bangladesh soon.

Bhattacharyya rounds up his insightful account with the following suggestion: ‘Implementing pragmatic strategies is thus imperatives, from a long-term perspective, while taking into account the sensitivities of the region.’ It can be said with some amount of certainty that, so far, the government at the Centre and in the state have tread carefully and wisely. Failure is not an option. Assam cannot be allowed to lapse into its bloody past.

You May Like This

Life is never too pointless to be ended

"Priye Sufi," a book by Nepali author Subin Bhattarai, is a moving and consoling book. The story's primary lesson is... Read More...

Mrityu Diary: A must read book about life and death

"Mrityu Diary" or the “Death Diary” is a book written by the author Tulasi Acharya, which is currently available in... Read More...

"Jiwanta Sambandha: A Medical Student's Resonance"

As a book enthusiast, I've always been drawn to the world of literature, seeking solace and inspiration within the pages... Read More...

Just In

- Heavy rainfall likely in Bagmati and Sudurpaschim provinces

- Bangladesh protest leaders taken from hospital by police

- Challenges Confronting the New Coalition

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

- NEB to publish Grade 12 results next week

- Body handover begins; Relatives remain dissatisfied with insurance, compensation amount

Leave A Comment