We have a demographic time bomb and a dependency sword hanging over our heads.

Had we been a European country, our youths would have launched multiple revolutions and overthrown their governments. Luckily for Nepal’s polity and the ruling class, our youths have a fatalistic attitude (courtesy of the Hindu belief) and accept the crisis they face as fate. They choose to migrate overseas for opportunities instead of confronting their ruling class.

Children aged 14 and under and older people aged 65 and over do not typically work. As a result, these groups tend to “depend” on the working-age population, defined internationally as those aged 15 to 64. The ratio of this dependent population of children and retirees to the working-age population is called the “dependency ratio.”

This ratio tells us quite a bit about a country’s economic burden. It paints a picture of what kind of issues the society may face in the future as this ratio changes.

If this ratio today is high, it means there are too many children and retirees who must be supported by a smaller working-age population. In this scenario, the economy strains under the weight of trying to provide for the dependents.

If this ratio today is low, it means there are more working-age people than the combined total of children and retirees. In this scenario, the economy could possibly observe surplus capital that can be mobilized to further grow the economy.

All countries would love to have a lower dependency ratio.

Historically, rich countries have seen more older people and lower birth rates. Therefore, while the older population may keep increasing, the low birth rate ensures the dependency ratio remains relatively stable in rich countries.

On the other hand, poor countries have historically experienced high birth rates and poor life expectancy. Therefore, while the younger population keeps increasing, the stable older population ensures the dependency ratio remains relatively stable in poor countries, for a while. After a while, the children come of age and turn into working-age people. Then, the dependency ratio falls rapidly.

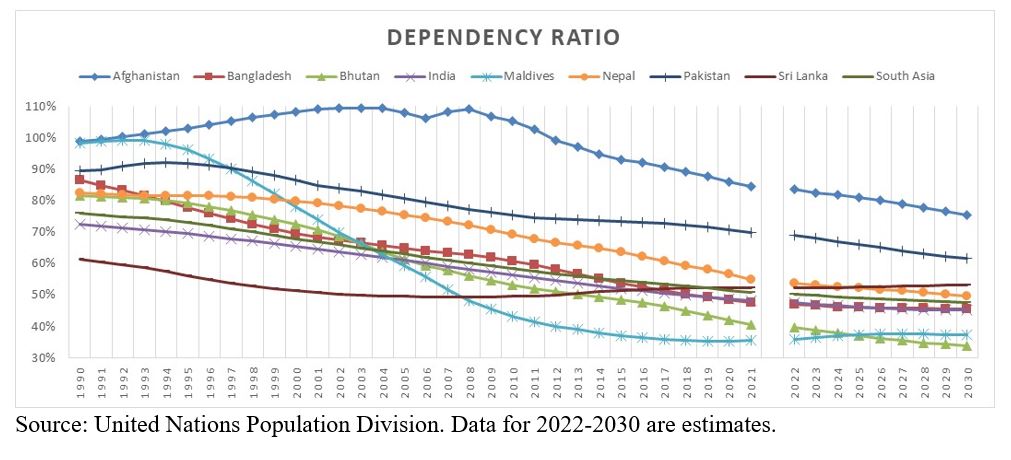

As a region that has remained historically poor, South Asia has experienced the latter, which we can clearly see in the data.

Nepal becomes self-dependent in egg

WHAT THE DATA SHOWS

In 1990, South Asian countries had a dependency ratio higher than 60%. That is, there were more than 6 “dependents” for every 10 working-age people in the region. Having 10 people working to ensure 6 dependents were taken care of strained the region’s resources. This meant less household savings, which meant less capital available for investments, which in turn meant low economic growth.

If we recognize the regional context of what a dependent population in South Asia is (for example, many graduate level students in South Asia don’t work and are fully dependent on their parents), it may very well be the case that 10 working-age people in the region actually supported 10 dependents.

By 2021, the average dependency ratio in South Asia fell to 51% (it was 76% in 1990). This periodic steady decline coincided with the region’s young population growing steadily over the same period and the region’s economy growing along with it.

Several factors contributed to the decline in this dependency ratio after 1990. For example, high birth rates in the 1980s and 1990s gave us children who became “working-age” adults by the 2000s and 2010s. High vaccination rates ensured our children survived into adulthood. Increasing literacy rates ensured our children were more educated than the generation before, which made them more productive and they contributed more to the economy.

Barring Sri Lanka, where the ratio is climbing up again, South Asia’s dependency ratio is on track to decline further. Therefore, unlike the rich countries around the world, where dependency ratios are steadily increasing mainly due to rising older population, South Asia is experiencing the opposite: our children from the last few decades are turning into working-age adults, becoming more productive, and helping grow the South Asian economies.

THE SOUTH ASIAN CONTEXT

While a falling dependency rate is good for us, there are problems with the concept and measurements of dependency we use.

We can safely argue that the dependency ratios for South Asia are incorrect because the definition of a “dependent” as someone aged 14 years and under and retirees 65 years and over does not accurately apply in our region.

For example, few 15- to 25-year-olds in South Asia actually engage in meaningful employment. Many parents fully support their non-working children attending universities. The US Embassy in Nepal recognizes this context and allows 20–21-year-olds in Nepal to be included as “dependent” when their parents win the Diversity Lottery. The point is, many 15 to 25-year-olds in South Asia do not satisfy the “working-age” definition used to calculate dependency ratio.

South Asians also retire years before they turn 65. Private sector workers in India can retire at 60 while government workers can retire at 65. In Nepal, government employees’ retirement age was recently increased from 58 to 60. All countries in South Asia have some form of early retirement options. Therefore, most South Asians retire much earlier than 65.

These retirees do not satisfy the “working age” definition but are still counted as working-age in official/international statistics. The regional pension systems fall short of meeting retirees’ livelihood needs. Programs to retrain and assist these retirees to gain new meaningful employment are lacking in the region. Most employment opportunities have explicit or implicit age restrictions, disqualifying many retirees from even being considered for those positions. As a result of all these reasons, many retirees in South Asia are fully dependent on their working-age children.

This means, the UN’s dependency ratio data for South Asia is still useful for making general observations, but misses important regional contexts and cannot be taken at face value for policy making purposes.

Therefore, the dependency data for South Asia is contestable, even when we ignore the fact that the very concept of “dependency” and the statistics created to measure it are both contestable. For example, scholars argue that popular dependency statistics support existing dominant social relationships and significantly limit the solutions we can generate to resolve the problems associated with dependency.

Even without going so far as to contest the very idea and definition of dependency, even a cursory understanding of the South Asia region is enough to challenge the notion and measurements that are currently being used.

Context matters in public policy making.

WHAT LAYS AHEAD?

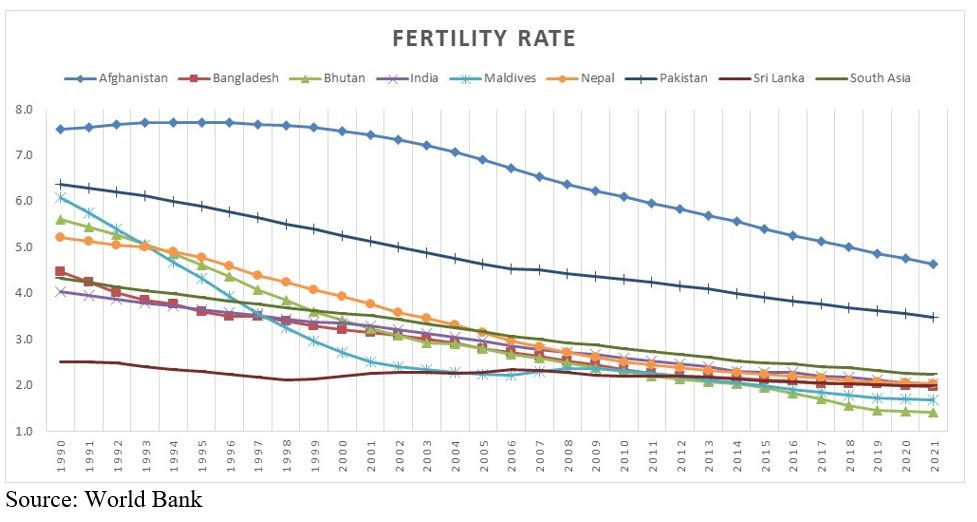

Most countries in South Asia had high fertility rates (number of children per woman) in the 1960—1990 period. All those children are today adults 30-63 years of age. Those high birth rates from decades ago coupled with rising life expectancies across South Asia means we have today a huge “young-old” class in the region—the group of retirees between 55 and 65 years of age.

The young-old are old enough to retire but young enough to enjoy several more decades of vibrant, healthy, and fruitful life. Most members in this group have monetary savings, real estate holdings, are probably landlords, and receive pensions. These help the young-old to lead a relatively affluent lifestyle compared to the younger generations, who are poorer and miserable if we go by news reports.

More importantly, this growth of young-old comes at a point of historically lowest fertility rates in the region. That is, we are not producing as many babies as before. Nepal, for example, had a fertility rate of 2.0 in 2021, which falls below the replacement rate (the number of babies we need to produce to replace the old people who die). That means, in the coming decades, Nepal will experience a population decline while the young-old group will remain a dominant force in the population.

This demographic change is happening at a time when Nepali youths face grim employment opportunities, growing weariness with the political process and the ruling class, and a growing sense of disaffection. Had we been a European country, our youths would have launched multiple revolutions and overthrown their governments. Luckily for Nepal’s polity and the ruling class, our youths have a fatalistic attitude (courtesy of the Hindu belief) and accept the crisis they face as fate. They choose to migrate overseas for opportunities instead of confronting their ruling class.

In the coming two decades, Nepal will become a country only of the young-old. We will have fewer young people and whatever young people we will have at that time will migrate and settle overseas. This will happen just as we start becoming a welfare state, taking care of the young-old and the really old, and we will need our working-age people contributing to the welfare state’s survival.

We have a demographic time bomb and a dependency sword hanging over our heads but our policy makers do not seem worried.They should be.