“Sometimes, it amazes me. What was I thinking!” he says.[break]

He walked for three days from Kakarbhitta to Biratnagar, sleeping and eating in temples, certain only of the fact that the tour should start from Mechi. He remembers the strength of his convictions then and how it’s fueled him through his travels. There were many bicycles in the eastern towns of Nepal and he expected to find a way to get one. And he did. He found sponsors and Nepalis ready to help, and with the kindness and generosity of people all over the world, has since been able to live, or rather, ride his dream. He’s been to 53 countries and arrived here in Geneva in time for Dashain celebrations.

But dreams aren’t enough, and Dahal recognized that he needed a purpose. Before he started out, he decided on a theme for his ride: Environment and Education. His bicycle was already a message in action for his environmental theme. The educational factor was built into the motivation for his journey and grew on his very first tour across Nepal.

“I was a pretty good student. I always did more than my homework, sometimes even the homework for the week to come,” he says. “But everything changed when a German cyclist came to our school and spoke about his travels, showed photos of the places he had been to. I felt I learnt so much in that hour, more than I had in the years of Social Studies and Geography classes.”

The German cyclist’s visit left a deep impression, and for a month, Dahal deliberated on his own need to experience a similar journey. He managed to get a bus ticket to Kakarbhitta through a friend’s connections. He lived with his brother in Tin Kune then and knew he couldn’t say a word about it unless it was to abort his journey even before it began. He needed traveling money, and small change was always left on the dining table. On the day Dahal decided to leave on his adventure, there was no money on the table. He checked his brother’s pockets and found papers, cards, and 25 Rupees. And with that amount, he

left home.

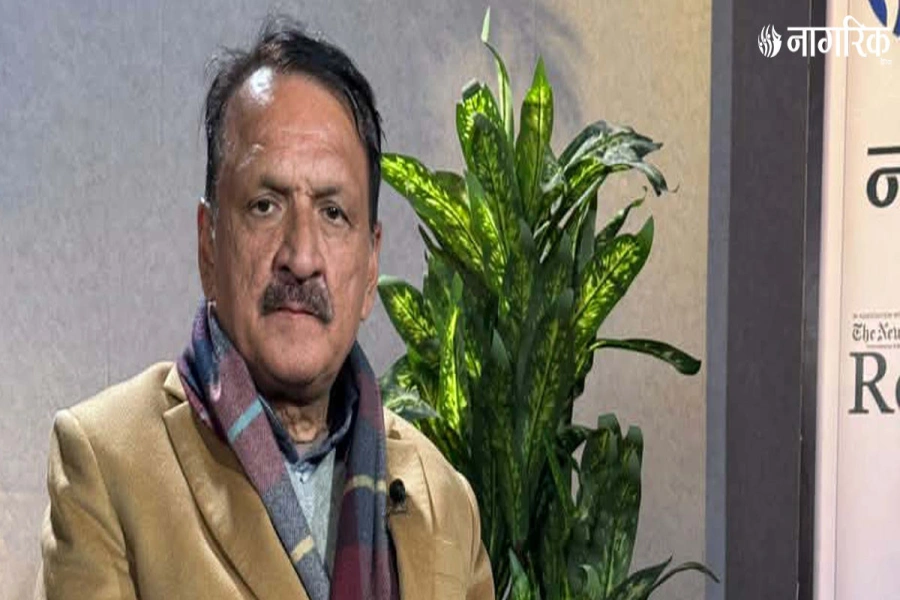

Saurab Dahal in Abu Dhabi, UAE

While Dahal was out pedaling, his family was coming to terms with his decision. His friends, neighbors and people who knew of him said he was a lost cause. But Dahal himself felt he was finally discovering a cause. He had always known the importance of education, but he had never felt it as keenly as when he began to cycle across Nepal’s rough terrain and stopped to meet with the students of the schools in the villages he passed through. He fashioned a banner stating his theme, and together with the flag of Nepal, began on his mission.

In Tumlingtar, he met students who walked an hour to get to the primary school. To attend secondary school, they walked three hours through leach-infested paths. He met students whose dreams were to wear a pair of pants with no holes or a new shirt that fit them well, clean notebooks to write in and brand new pencils still unsharpened.

“All they really wanted was decent uniform and stationeries. It humbled me greatly. I felt like I’d done nothing in my life,” he says.

The money Dahal received as funds from the CDOs (Chief District Officers) or people he met, he gave to the schools and to the students. He remembers the children he met and two in particular. One was Man Bahadur Nepali, a young Dalit boy in Kailali at Rastriya Higher Secondary School, whose parents worked as gravel crushers.. Man Bahadur’s shoes were badly torn, and in the course of their conversation, the young boy said he wanted to attend school but didn’t go because his shoes were torn. So Dahal bought him a pair of shoes and a shirt.

In Tansen, he met another young boy who sniffed Dendrite. Armed with good intentions, Dahal also bought him clothes and stationery to go to school. The next day, he found out that the boy had sold off all Dahal had bought for him and was back in the streets. Dahal also learnt that the boy had been labeled a lost cause by activists and organizations that had come before him and tried to put him in school. He went looking for the boy, and when he found him, sat down and had a long conversation.

“I get news of him. He went back and he’s still in school,” says Dahal.

Once his tour in Nepal was over, Dahal set out to travel across national borders. He went to countries without bike paths, pedaled across distances with his rations depleting, unsure of when he could next refill his bottles of water or replenish his food.

“I’ve come close to giving up many times, have wondered what I was doing in the middle of nowhere on a bicycle. But when that moment is over and I’m back in shape, I know I can’t stop yet,” he says.

News travels fast today, and with the Internet, things have become easier. Dahal stays connected as best as he can, shelling out money for Internet connection, even when he has to make a choice between the web and food. He’s learnt the rules of the road, and sends emails to embassies ahead of time when he can, makes connections through Facebook, and travels with mapping software that are able to give him an idea of when and where. In places like Mongolia where he couldn’t connect with Nepalis, he was met warmly by the Indian Embassy. He’s been across Asia, Australia, Africa, and the Middle East, stopping at schools and environmental agencies. The Qatari Government’s Cycling Federation met with him and he counseled them on making bike paths and holding events.

“In Nepal, too, the movement has begun. Kathmandu is a very cycle-able city and we need safe bike paths there. It would help cut down traffic jams, cut down our fuel dependency and make us all healthier and the city less polluted,” says Dahal.

But Dahal is aware that the task is easier said than done. “The biggest obstacle in Nepal is our attitude to cycles and cyclists. People look down on you if you ride a bicycle and dream of cars and motorbikes. That’s a fundamental problem. We need to change such attitude. Look at developed nations. In Holland, even the prime minister goes to his office on a bicycle. On the road, the first priority is always given to walkers, then cyclists, then other vehicles. If our prime ministers, ministers, and celebrities started riding bicycles, even just once a week, it would set an example and accelerate our change in attitude.”

Dahal doesn’t limit himself to cycling, though. While in Qatar, he was also featured in Nabin Bhattarai’s music video “Sochda Sochdai,” and has recently received an offer to act in a film. He’s also been back to Nepal to attend the wedding of the brother whose money he had stolen.

“The 25 Rupees? He’s my brother and I don’t yet intend to pay him back. It may take four more years to finish my tour,” says Dahal, laughing.

Once done with his tour in Switzerland, Saurab Dahal will be cycling to other European nations before setting out to travel in America.

Round Table Nepal concludes “PADelux Girls on Wheels”