OR

Teachers considered teaching computers an additional burden and expected to be paid ‘extra’ for it

Online Learning Exchange Nepal (OLE Nepal), launched in 2007 with the aim of using technology to transform learning through engagement, exploration and experimentation, is official ‘technology’ partner of the Ministry of Education. It will celebrate 10 years of online learning in Nepal soon.

According to its website, in the past decade, it has sent 5,000+ laptops in 200+ schools, trained 1,000+ teachers on integrating ICT in the classroom teaching-learning process, developed 600+ learning modules to be used by teachers, and created a digital library with 6,000+ books and other items used in schools and community libraries. It now covers 208 schools spread over 32 districts and is perhaps the single biggest government initiative to bring technology into classrooms.

Poor results

A couple of years after its launch, OLE assessed its impact. Its report says several factors led to lack of significant impact on student learning: The program is relatively new and thus it is too early to gauze its impact, not all teachers took one-week intensive training held before program launch, some teachers may not have used available digital resources due to the increase in workload that this entailed, and digital content, while following the curriculum taught in school, was too difficult for students to grasp.

The results were disappointing, with no effect on student test scores even though both teachers and students reported liking the digital contents and finding them useful. While everyone expected technology to make critical impact on learning process, the results went against all popular notions and beliefs.

This reminds one of an excerpt from Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen’s book, Freedom as Development, which highlights how we as humans often tend to be thoroughly ‘disillusioned’ while in a pursuit of a singular goal. The story goes like this.

Bordering the Bay of Bengal, there is Sundarban—a beautiful forest—a natural habitat of the famous Royal Bengal Tiger, but whose population continues to dwindle. Surviving tigers are protected by hunting bans. The forest is also famous for honey. Desperately poor people living in the region go to the forest to collect honey that fetches a handsome price in urban markets. But honey collectors also have to escape tigers. In a ‘good year’, a minimum of 50 or so honey gatherers are killed by the tigers. While the tigers are protected, nothing protects the miserable human beings trying to make a living from the woods.

While one may think it is stupid to venture into a dangerous protected area, one should remember that human inhabitants once coexisted with the tigers. Keeping the tigers in an enclosed area may have helped save more tigers, but at the cost of daily livelihood of people and often even their lives.

Culture v computer

Seymour Papert, the late professor at MIT’s Media Technology, once said that the context for human development is always a culture, not an isolated technology. His idea was that in the presence of computers, cultures might change and with it so will people’s ways of learning and thinking. But if one wants to understand (or influence) the change, one has to pay attention to the culture—not the computer.

Perhaps this helps us understand “Technocentrism”—a term attributed to Papert—which means that the person has difficulty in understanding anything independently of the self.

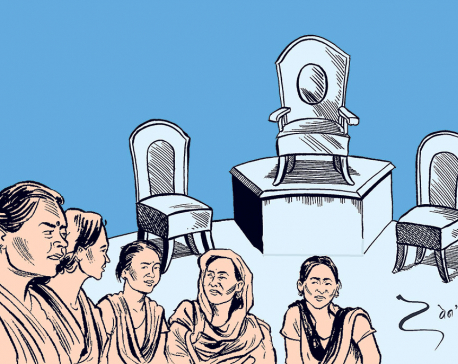

Survey of Factors Affecting Teachers with Technology (SFA T3), carried out in the schools across Tasarpur area of Dhading district, had many interesting findings. It showed that teachers considered teaching computers an additional burden. This meant they expected to be paid ‘extra’ for this. As things stood, they had no motivation to teach computers or teach with computers. This was highlighted by the fact that in Syangja, which probably has highest student-to-machine ratio, teachers would either not attend training session or disappear from the second day.

As one Kathmandu University computer science graduates who has been working as a computer trainer to teachers in remote Nepal told me, they were absent as they did not get daily allowances.

Behavioral theorists have come up with several models for why technology adoption often does not produce desired results. Technology, in itself, is no good. It’s meaningful only when it is put to good use. One of the widely used theories, Technology Adoption Model (TAM), posits that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use determine an individual’s use of a system. Perceived usefulness is also seen as directly affected by perceived ease of use.

If we were to use the model to gain a deeper understanding between ease of use and perceived usefulness, the latter seems to be the answer to non-adoption of technology. Teachers admit that it’s the age of computers but they cannot convince students why they are useful.

In most schools, the textbooks are in Nepali. Everyone is taught to ‘Google’ the terms. So when the teachers type out the word, for instance, Gurutwokarshan (“gravity”) teachers and students expect to find a lot of information as they are accustomed to hearing that one can find almost anything online.

This author tried only to discover that there were just two YouTube Nepali classes. The rest were in Hindi.

In Papert’s words, we still seem driven by technocentric thinking. Drawing parallel with the case of Sundarban, we might be building beautiful computer labs but the teachers may be acting as ‘victims’ rather than beneficiaries.

We should understand that technology in Nepal’s schools is also a cultural and a social issue.

hiteshkarki@gmail.com

You May Like This

Enough is enough

Many people were killed in charge of practicing witchcraft. Those cases were resolved most probably with milapatra ... Read More...

China drafts rules on biotech after gene editing scandal

BEIJING, Feb 27: China has unveiled draft regulations on gene-editing and other new biomedical technologies it considers to be “high-risk.” Read More...

Technology expo focuses on home-grown products

KATHMANDU, Feb 18: The third edition of tech-exhibit Mantra: Chanting of Technology concluded at the Pokhara City Hall in Pokhara this... Read More...

Just In

- Nepal at high risk of Chandipura virus

- Japanese envoy calls on Minister Bhattarai, discusses further enhancing exchange through education between Japan and Nepal

- Heavy rainfall likely in Bagmati and Sudurpaschim provinces

- Bangladesh protest leaders taken from hospital by police

- Challenges Confronting the New Coalition

- NRB introduces cautiously flexible measures to address ongoing slowdown in various economic sectors

- Forced Covid-19 cremations: is it too late for redemption?

- NRB to provide collateral-free loans to foreign employment seekers

Leave A Comment