OR

Girls can do anything, right - but what about boys? Why do parents still get sideways looks when their boys wear a dress, or play with a doll? In the era of #MeToo this narrow definition of masculinity matter - and the roles we assign kids at birth can have devastating impacts.

When Laura* first emerged from the drama of labour and saw she had given birth to a baby boy, she was devastated.

"It feels awful to acknowledge but in that moment when I knew I was meant to be filled with awe and wonder, I just felt my stomach drop and felt incredibly sad. I knew it wasn't something I could say out loud so I tried to push it aside. It was probably a week or two later that I was able to name the grief I was feeling."

When the Christchurch mother got pregnant with her second child, she knew there was a 50 per cent chance it would be a boy. But she had convinced herself it would be another girl.

Vincent, 9, is growing up in the #MeToo era. Photo: JASON DORDAY/STUFF

She was "in such denial" that she only discussed names for a boy with her wife two nights before the birth.

Laura was worried she and her wife would not be equipped to raise a boy – an idea she now realises stems from internalised homophobia.

"I worried that we would have to do things differently to what we had with our daughter. That there was some 'other way' of raising boys and that I simply wasn't equipped to do this. I think this was in part linked to stereotypical ideas around boys being 'boisterous', 'rough and tumble' and like this was the kind of parenting we needed to do."

As Laura was struggling to come to terms with her fears, stereotypical comments abounded.

When she introduced her son to family and friends, someone commented that he was "such a boy".

"I remember driving home thinking, what the hell does that even mean? He was a six day old tiny human in a car seat."

Visitors marvelled at his long eyelashes: "Gorgeous eyelashes are wasted on boys".

Gender stereotypes were nothing new. Laura had felt confident fighting them with her daughter, but it seemed more problematic with her son.

"Like I will be stopping him from 'being a boy'."

THE TESTOSTERONE FALLACY

AUT senior lecturer Pani Farvid says gender stereotypes are harmful for boys and girls. SUPPLIED

Auckland University of Technology Psychology senior lecturer Pani Farvid gets fired up on the phone telling me such gender stereotypes are not based on sound science.

The "fallacy" that men and women are hard-wired differently from birth – men are fuelled by testosterone, men are from Mars, boys will be boys... – has been perpetuated through "pop psychology".

"We know from research that it's just not true. Forty years of psychological analysis has found that overwhelmingly men and women are more similar than they are different."

The Y chromosome only dictates the reproductive system - whether we get penis or not, Farvid says.

Australian psychologist Cordelia Fine rubbishes the idea of fundamental differences between men and women in her 2017 book Testosterone Rex, which won the prestigious Royal Society prize for science book of the year.

Testosterone does effect on brains, bodies and behaviour (men are more hairy, have deeper voices and tend to be taller), she writes, but it isn't "the potent, hormonal essence of competitive, risk-taking masculinity" we assume it to be.

BOYS CAN'T DO ANYTHING

These days most parents would agree that girls can do anything, including wearing blue pants, playing with trucks and being good at maths.

But boys still can't do anything. They risk at best ridicule and at worst being told off when they cry, play with dolls, wear pink - or shock horror, a dress.

The Gender Attitudes Survey, released earlier this year, found that ideas around traditional gender roles are still entrenched, albeit contradictory.

Parents are reassessing how they raise their boys in the wake of #MeToo. /JASON DORDAY/STUFF

Just over half of the 1251 Kiwis surveyed thought boys should be able to play with dolls, for example, while one in five people felt it was more important for a man to be in a position of power.

So, while most of us believe women should hold positions of power, we still believe in cultivating male rulers and female nurturers.

Farvid says behaviours and traits associated with masculinity increase a person's status while stereotyped feminine conduct - being passive, nurturing, quiet, gentle - reduces it.

"If a man does feminine things, he is trading down. If a woman does masculine things, she is trading up."

Farvid urges parents to question their "old fashioned" beliefs around gender.

Imposing a narrow ideal of masculinity on boys makes them shut down their feelings, with anger the only socially acceptable emotion for boys and men, she says.

This means men living with anxiety and depression are less likely to seek help, and men are more likely to take their own lives.

"Men are the silent sufferers of masculinity. If we challenge problematic masculinity, men will suffer less, die less and get hurt less."

DISTORTED MASCULINITY

A growing body of research suggests that men who struggle to regulate and express their emotions are more likely to become violent and to use substances, which is also linked with sexual violence.

Sociologist and criminologist Michael Roguski says "distorted masculinity - a sense that to be a man you have to engage in certain stereotypes" leads to negative outcomes such as domestic violence and suicide.

Sociologist and criminologist Michael Roguski says gender stereotypes lead to negative outcomes.SUPPLIED

Roguski did a study looking at former perpetrators of family violence who turned their lives around. He found that for them, violence was not only normalised but normalised in the context of what it means to be a man.

New Zealand's "high bullying culture" targets people who don't fit the gender mold, rendering LGBTQI populations "extremely vulnerable".

"Rates of family violence go up when New Zealand loses a major sporting event what does it say about our masculinity?

"Our reliance on alcohol and sporting and this weird patriotism that we have to do with rugby, to me, is an indication that what we are valuing is wrong. This is a conversation parents should have with young boys and girls."

Why do parents still get side looks if their sons have long hair?/JASON DORDAY/STUFF

In the wake of #MeToo, this might be a conversation parents are starting to think about. Over last few months, publications including The New York Times, the Guardian, Slate and The Telegraph ran opinion pieces and articles about raising boys to be good men.

Farvid says we should see this as an exciting opportunity rather than a challenge.

"Boys will be boys is a cop out. Historically boys have had more leeway to get away with problematic conduct and that needs to change. The #MeToo movement is dealing with that head on.

"We need a shift in mass consciousness about how we deal with this stuff. Hopefully we are in that moment and hopefully the next generation of boys will be more gender inclusive, ethical, emotionally aware, and won't use power and control to get status."

BUZZKILL

Auckland communications specialist Rebecca Wadey knew raising her two sons was a big responsibility, long before the #MeToo movement started.

Auckland communications specialist Rebecca Wadey with nine-year-old Vincent./JASON DORDAY/STUFF

"White middle-class males are often not punished for their bad behavoiur and that's disgraceful. I want my children to grow up feeling accountable."

Wadey and her husband Ant Timpson regularly talk to their sons Toby, 11, and Vincent, nine, about consent, permission, respect and consequences.

Those conversations aren't forced. They just happen as part of everyday life.

On a recent drive out of town, the family saw anti-abortion signs.

"The kids asked what it was so we talked about how a pregnancy can be wanted or not, and how it's men and women's responsibility."

Wadey jokes she often becomes the "buzzkill" when they all sit together to watch 90s movies and TV shows.

"If I see something problematic coming up, I will say: 'did you see how he implied that she is not pretty and won't get the boy?' I catch it as soon as I see it and call it out."

Sometimes, Wadey takes the conversation "a bit far".

"I had an old 1970s home-birth book and I joked to Ant that I should leave it lying around so the boys could see different types of naked women - bigger, or with bush. Things that teenage boys don't see on the internet.

Wadey and her two sons Vincent, 11, and Toby, 9, in their Auckland home./JASON DORDAY/STUFF

"But he was like: 'Nooo' and that was one occasion where he thought I was taking it too far."

Timpson works in the film industry "so the problematic representation of women in movies is a constant conversation in our life".

Wadey, a breast cancer survivor who has had a mastectomy, wants her sons to have realistic expectations about what women look like.

"It's not like I walk around the house naked all the time but I have always been very clear that women come in all shapes and forms and I really hope that by the time they have a phone or computer of their own, they remember it is a filtered world that they are viewing."

At home, Wadey and Timpson model equality.

"We definitely co-parent. He cooks dinner most nights and makes lunch boxes and takes them to school every day because I start early. They don't see traditional roles in our house."

Rebecca Wadey regularly talks to her sons about consent, permission, respect and consequences.JASON DORDAY/STUFF

A WAR AGAINST LITTLE BOYS?

Not everyone thinks we need to reassess how we raise boys in the #MeToo era.

Some even fear the movement is hurting them. In October, Donald Trump said it was "a very scary time for young men in America". Conservative parents in the United States talk about arming their sons with body cameras and consent forms so they don't get falsely accused of rape.

Those fears are not rooted in fact. False rape complaints are rare, making up between 2 and 8 per cent of sexual violence cases reported to police. Far more common are the women who never report rape or sexual assault because they fear no one will believe them. In New Zealand, only an estimated 9 per cent of sexual violence cases are reported to police. Fewer than one-third of these will progress to prosecution and overall, 13 per cent of recorded cases will result in a conviction.

Still, US philosophy professor and self-described 'factual feminist' Christina Hoff Sommers says looking at how we can raise boys differently is "an overreaction".

Controversial US academic Christina Sommers says the #MeToo movement will fail if it devolves into a war against men and little boys./SUPPLIED

"Because some men have behaved abominably – all little boys need to be re-educated. Who thinks that way," she asks in an email response to my questions.

Of course, boys need to be civilised, she says. "Proven social practices" to achieve that include letting them "develop a sense of honour and help (them) become considerate, conscientious, and gentlemanly".

"This approach respects boys' masculinity and does not require that he play with a Hello Kitty tea set."

"Hardline varieties" of feminism see women as victims and men as oppressors, she says.

"This male-averse style of feminism, popular in many teacher's colleges, views little boys as carriers of a pathogen known as masculinity."

Hoff Sommers says the #MeToo movement "has the potential to be world-transforming" but to succeed it has to be something men and women achieve together.

"If it devolves into a war against men – and little boys, it will fail."

BOYS WILL BE SOFT

Melbourne writer Clementine Ford would probably fall into what Hoff Sommers sees as "hardline feminism".

Internet trolls and men's rights activists have accused her of being a man-hater, a feminazi, and other names that are unfit for this publication.

Feminist writer Clementine Ford just released a book called Boys Will Be Boys./SUPPLIED

Her latest book, Boys Will Be Boys, is a deep dive in the darkest depths of male entitlement and rape culture.

But Ford rejects the idea she is waging a war against men and little boys.

Questioning toxic masculinity is not saying all men are terrible: "It's saying society is enabling men to do terrible things," she says on the phone from her Sydney hotel while on promo tour for the book.

In Boys Will be Boys, she writes: “One of the many benefits that will come from dismantling the patriarchy is the liberation of boys and men from its grip”.

And she tells me the book left her "with a lot of tenderness and soft feelings towards men".

"Because I see the potential for them to break out of this mold and I see how much they want that from men I have talked to since the book came out".

Ford started writing Boys after giving birth to her first child, a son, which she describes as one of her "toughest challenges yet as a feminist".

Part of the challenge is to cultivate softness in him, in a world that will tell him that being soft is not manly as he grows up.

Clementine Ford with her son at home. She says becoming mum to a boy is one of her "toughest challenges as a feminist yet"./SUPPLIED

"My son is pretty gentle generally and I love that about him but when he is going through more grabby, pushy stages, I feel uncomfortable. I really hate that other people will respond to not only their sons but to other people’s sons by saying: 'Oh, he’s just being a typical boy'. I don't want him to receive that message that this behaviour is OK.

"All kids do it but it gets conditioned out of girls and excused in boys. I also don't want people to tell him not to cry or to be a big boy."

For now, Ford's son is in shared care with a small number of other preschoolers "where everyone has the same values". But Ford and her partner know they can't keep him in this bubble forever.

"We are worried that the message we are trying to give him about choice and being gentle and sensitive and kind and nothing being for boys or girls will be discounted as soon as he gets into the school yard. It will be easy to undo all those teachings because the drive to be part of the pack is so strong."

She says expectations around masculinity are changing in the #MeToo era but in mainstream circles, people still place the onus of prevention on their daughter.

John, Ephraim (7) and Zipporah (3) and Maria Milmine with their dog Obie at their Cambourne, Porirua home./KEVIN STENT

"I often hear from parents that they're frightened of having girls in this world. We know what violence can be done to our daughters, and people on the whole seem desperate to find a solution to this… Curiously, this search for solutions has yet to include looking at ways to change the behaviours of boys," she writes in Boys.

Ford urges parents to talk to kids about consent from a young age.

"I am not saying that you should talk about sexual consent to a two-year-old, but you can make them aware of the idea of consent. If they are playing with another kid and that kid says they want to stop, then they have to stop. If they don’t want to give someone a hug, they don’t have to. Teach them that they have autonomy."

YOU CAN'T TOUCH MY PENIS

For Wellington designer John Milmine, actively challenging gender norms and teaching his children about bodily autonomy are top priorities.

John Milmine wants to teach his seven year old son Ephraim how to express emotions./KEVIN STENT

John and his wife Maria are not afraid to talk to their seven-year-old son Ephraim and three-year-old daughter Zipporah about sexuality and consent.

Ephraim has a book on sexuality and knows how babies are made.

When he was about three, he once introduced himself to the checkout operator at the supermarket by saying: "Hi Nicole, you can't touch my penis", John recalls with a laugh.

"He seems to get the message."

John says many parents avoid these conversations because they think their children are too young.

"But we want to be the first voices for those topics for the kids so they have something to compare it to when they get to school."

Ephraim and Zipporah learn to respect each other's privacy when they are getting changed at home. They are not getting baths together anymore now that they are older.

John Milmine is not afraid to talk about sexuality and consent with his children./KEVIN STENT

"Zipporah is at a stage at preschool where they're all laughing about bums and pulling pants down. We try to teach them it's not something to to laugh about. It's normal, not embarrassing."

John talks to Ephraim about respecting her sister as her own person even if she is smaller than him.

"It's making sure he gives her space and listens to her and respect her sovereignty around her own body, interests and toys."

Ephraim has always been a "quiet, sensitive boy", John says.

But he still tries to help him express himself when he is sad, disappointed, annoyed or angry.

John Milmine and seven year old son Ephraim near their Porirua home.KEVIN STENT

"We want him to be in touch with his emotions. We don't want anger to be written off as testosterone. We want him to process it in helpful ways."

TIPS FOR PARENTS

So what can parents do at a practical level to make sure their sons grow up to be good men?

- Allow boys to show emotion - and not just until they are eight or nine.

- Be conscious of what you model at home. Heterosexual parents performing rigid roles teach kids from a very young age about what it means to be a husband or a wife, a father, a mother, Farvid says. Women who work outside the home still do half as much more unpaid labour on average weekly than men. That doesn't mean traditional family set-up with mum at home and dad at work is bad modelling, she says. What is important is teaching kids that what works for your family doesn't have to be the same for everyone.

- Respect children's privacy and bodily autonomy. Don't force them to give hugs and kisses.

- Talk to your children about consent, gender norms, men and women's representation in the media and what it means to be a good person. Regular conversations in the car, at the dinner table, while watching TV play a role in raising empathetic children. Research suggests that most kids will eventually adopt parental values imparted in a loving way.

- Watch out for benevolent sexism. These days overt sexism is rare. It's become more insidious. Seemingly respectful acts such as men opening doors for women or taking heavy loads off their hands can send the message that women need protection because they are weak. Inferior.

*Not her real name.

You May Like This

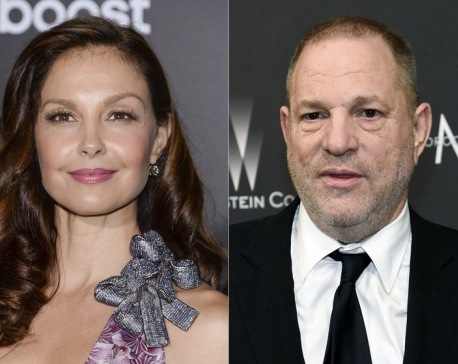

Court says Judd can sue Weinstein for sexual harassment

A federal appeals court on Wednesday restored a major part of Ashley Judd’s lawsuit against Harvey Weinstein, finding that the... Read More...

Sexual harassment complaints strain human rights agencies

HARTFORD, Sept 4: A wave of sexual harassment complaints that accompanied the #MeToo movement is straining many of the state... Read More...

As MeToo unnerves China, a student fights to tell her story

QINGDAO, China, Sept 1: The sight of five burly guards blocking the way out of her dorm filled Ren Liping... Read More...

Just In

- World Malaria Day: Foreign returnees more susceptible to the vector-borne disease

- MoEST seeks EC’s help in identifying teachers linked to political parties

- 70 community and national forests affected by fire in Parbat till Wednesday

- NEPSE loses 3.24 points, while daily turnover inclines to Rs 2.36 billion

- Pak Embassy awards scholarships to 180 Nepali students

- President Paudel approves mobilization of army personnel for by-elections security

- Bhajang and Ilam by-elections: 69 polling stations classified as ‘highly sensitive’

- Karnali CM Kandel secures vote of confidence

Leave A Comment