OR

Nepal Police making strides in community partnership

Published On: December 28, 2019 07:59 AM NPT By: Anjali Subedi

KATHMANDU, Dec 28: After many years of trial and error, Nepal Police has finally figured out a way to make community police functional. The Community-Police Partnership (CPP), launched by the law enforcement agency over a year ago, has reached out to thousands of local committees in making crime control a shared responsibility. A 64-year-old institution, Nepal Police first attempted to work with the community in 1982 through ‘Chhimeki Prahari’ (neighborhood police). Community police service centers were established in 1994, ‘Police My Friend’ was launched in 2016 while ‘Tole Tole Ma Prahari / Service With a Smile’ were popularized in 2017. However, these measures could not be efficient due to the lack of a clear vision, well-defined structure and a workable mechanism as the CPP now has, according to the stakeholders. Nepal Police has invested Rs 36.4 million this fiscal year provided by the government to execute and expand the CPP across the country.

“CPP is a solid mechanism to raise awareness, build trust and combat crime as the stakeholders feel included into the process and have found defined roles. The system involves stakeholders from the policy level to the ground level in mobilizing budget, resources of municipalities, wards, etc which was not the case earlier. The mayor’s office placed dozens of CCTVs and LCDs in the city in a year which have proven to be an important tool to control crime,” says DIG Sailesh Thapa Chhetri. “It is the result of CPP that I reached out to over 6,000 young students last year alone,” he added.

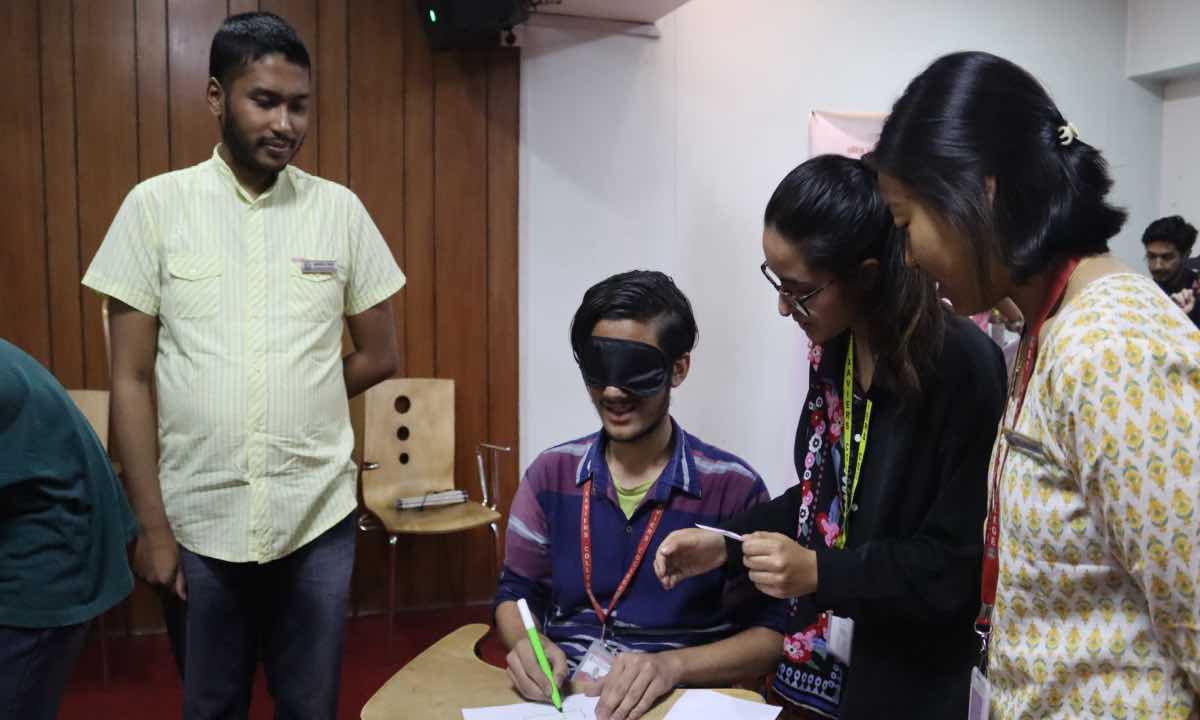

Under ‘One day with Police’ – a strategy to build connections and educate young people about security awareness, cyber discipline, domestic violence and helplines -- DIG Chhetri visited several Kathmandu-based schools. Many school children and teachers also attended classes at his office at the Metropolitan Police Office, Ranipokhari (he has been recently appointed spokesperson of Nepal Police). Such visits are arranged by Police School Liaison Committees formed under CPP with an aim to routinely include all schools in the locality in the program. Thapa is among nine dozen special trainers who trained 10,632 police personnel for institutionalizing the concept.

Until last year, the police in the Valley would normally get 200 phone calls a day at their hotline 100. Now the number of calls both for help as well as to leak information to police ‘regarding suspicious activities around’ has jumped to a whopping 350 plus, which DSP Hobendra Bogati, spokesperson for the Metropolitan Police, attributes to the outreach program. Interestingly, the victim (the high-profile sexual abuse case of former speaker Krishna Bahadur Mahara) had dialed police at 100 and the CCTVs had become instrumental in locating the suspect’s whereabouts at the given time.

“If we go through the data of the previous years, there has been a slight uptick in the number of calls to 100. A sudden rise this year, we believe, is because of the massive programs and CPP advertisement,” Bogati said. “The difference before the launching of CPP and now is that now the public feels free to provide information,” he added, citing interesting cases of crimes the police cracked on the basis of information leaked by the public.

Social worker Ujjwal Thapa, who was featured by Republica in October for his tireless service to helpless patients, also reports that CPP has been effective. “I remain out of the station quite often and have to deal with the police and other bodies for several reasons; I think CPP is making a difference,” he said.

Inspector Govinda Panthi, in-charge of Sankhu Police Range, Kathmandu, says the CPP has ‘made him popular in his area,’ letting people report their problems without hesitation’, which in turn puts pressure on him to meet their expectations. One of the examples he cited was a 13-year-old girl who had eloped with a drug abusing boyfriend could be rescued on time ‘due to awareness, and collective effort’. The girl from Shanti Pathshala Secondary School, Sankhu, had followed her boyfriend to Sindhupalchowk after he threatened to kill himself if she refused to elope with him. At home, she told she was going to school.

The school principal Devendra Shrestha, along with some senior students and teachers, had attended ‘one day with police’ just two weeks before the incident. Shrestha’s perception toward police had changed. “The session with the police helped build trust, develop inter-connection. We immediately felt like reporting the missing girl case,” said Shrestha, adding that the search began within an hour of the girl going missing in the morning, and the girl and boy were caught in Sindhupalchowk the same day.

According to Babita Jaiswal of Bara, president of Bara Women’s Network, women’s access to the justice system has improved at the grassroots due to the CPP. “Public hearings, audit, interactions are held every three months. They have to face us, answer us; this enhances transparency and accountability. On the other hand, police have now become more resourceful as local bodies facilitate them due to the MoUs signed between the partners,” she said over the phone.

Under CPP, there are 753 local units in 77 districts which have 6,334 Community Police Ward Committees, 7,944 Community Police Tole Committees and 8,631 Police School Liaison Committees that work on 12 different thematic areas to create a safe and secure community.

The story of CPP goes back to decades. From the time he joined the police force as an inspector two and a half decades ago, the present police chief Sarbendra Khanal would debate with his seniors for overbearing responsibilities of the police without much resources and support. He would press for full-fledged programs to enable the community police to function effectively. The government would not provide any extra budget, and the organization itself would not be able to plan things on its own. During presentations, police officers would come up with one or the other idea to keep it right but nobody would take it to the end. “After much back and forth, we compromised with simple initiatives like police my friend or service with a smile and so on,” he said.

After Khanal was appointed IGP in April last year, his first to-do list included successful implementation of this concept. When the preparations were underway and he was in his course to take PM and the Home Minister in confidence to include it in the Red Book, the rape and murder of Nirmala Panta in Kanchanpur put everything in the back-burner, and the case is yet to be solved. He later formed the ‘best team’ to carry out the necessary homework, including rounds of consultations with the government’s key players, planning commission, local units and social institutions.

“Our team worked hard to push forward the CPP. “Sophisticated equipment or modern technologies alone do not bring down crimes. Or else, there would be no shootings in countries like the USA. So, the right direction is a systematic outreach to the community, building connection and trust and raising awareness, like the CPP,” Khanal said.

Additional Inspector General of Police (AIGP) Pushkar Karki says that the CPP is a huge move that has the potential to reshape policing in the long run, but he pointed to the need for overcoming some challenges. “Our IGP took the initiative and this is now taking momentum; the government is stable, everything is fine. Now the challenge is to incorporate the next generation of police into the CPP. Local government actors, and other stakeholders should equally internalize it to ensure that the CPP thrives and lasts; so we must continue working on this part, “ he added.

Nepal Police officials during a public hearing organized in Dhankuta district a few weeks ago. Photo: Republica

You May Like This

Home Minister Lamichhane asks Nepal Police and APF for details of plain-clothes police personnel

KATHMANDU, Jan 5: Nepal Police and the Armed Police Force (APF) have been instructed to furnish the details of ‘ghumuwa... Read More...

US national arrested on charge of paedophilia from Pokhara

KATHMANDU, March 30: Nepal Police's Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) arrested a 66-year-old American national on charge of paedophilia, on Tuesday. Read More...

TU joins hands with Nepal Police's CPP program

KATHMANDU, July 2: Nepal Police has started a partnership with the country's oldest university, Tribhuvan University, in conducting research on... Read More...

Just In

- First meeting of Nepal-China aid projects concludes

- Lungeli appointed as Minister for Labor and Transport in Madhesh province govt

- Bus knocks down a pilgrim to death in Chitwan

- One killed in tractor-hit

- Karnali Chief Minister Kandel to seek vote of confidence today

- Chain for Change organizes ‘Project Wings to Dreams’ orientation event for inclusive education

- Gold price decreases by Rs 200 per tola today

- National Development Council meeting underway

Leave A Comment