OR

How hydro companies are cheating shareholders

Published On: February 17, 2020 07:59 AM NPT By: Rudra Pangeni | @rudrapang

People who invested in hydropower shares are in debt

BHATTEDANDA, LALITPUR, Feb 17: Anil Syangten, a farmer of Bhattedanda village in Lalitpur district, borrowed Rs 100,000 at 24 percent interest from a local moneylender three years ago and invested in shares of Khanikhola Hydropower Co Ltd (KKHC). He was one of the hundreds of investors who believed that investment in initial public offering (IPO) of a hydropower project was like buying gold.

Syangten, who sells surplus milk and vegetables for a living, is yet to recoup his investment. He had to use all his savings of the last two years to pay back the loan and interest. “The stocks have now emptied my pocket and I have no savings at all,” said Syangten. The poor farmer from Khanikhola of Lalitpur repents that his investment has gone to waste. The stock price of the 6.36 MW project has lost 30 percent of its value, and the dividend he receives is paltry.

He is among several families in Bagmati Rural Municipality who regret borrowing money at a high-interest rates and squandered their investments. Syangten is also identified as a ‘project-affected families’ by the project, as his house is close to the intake structure. These families are eligible for preferential rights or claims to project benefits and more IPOs were accordingly allocated for them.

Almost every household in the three VDCs – Bhattedanda, Ikudol, and Shankhu – (currently Bagmati Rural Municipality) had pinned their hopes on the hydropower project in their area. Three years on, no one knows why they haven’t received the promised return on their investments.

In 2008, the government introduced a policy to allocate a minimum of 10 percent of equity shares to the project-affected communities. The policy was designed to share benefits among local people as well as thwart possible local obstacles in project implementation. This policy has failed to meet its intended goal as exemplified by the case of KKHC.

The company collected Rs 46.57 million from project-affected communities in the district alone while the general public across the country poured an additional Rs 93.1 million.

The company blames the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) for its lackadaisical performance in building transmission lines. The chair and executive director of KKHC, Bijay Man Sherchan, said the NEA did not compensate the company for lack of power lines, which affected the company’s financial health. He said, “Most of the electricity during the rainy season is wasted because the NEA has yet to build transmission lines to evacuate power.” The NEA had promised to buy power from the project while signing the power purchase agreement (PPA), according to him. NEA owes Rs 250 million to the KKHC, according to the company executives. Sherchan added, “If NEA had paid that amount to us, we could be in a position to pay a minimum of 10 percent dividend to our shareholders every year.”

Work on the transmission line being built by the company itself to transmit energy to NEA’s nearest substation is in the final stages, Sherchan said.

NEA’s Managing Director Kulman Ghising, meanwhile, said they could not build the transmission line due to obstruction by locals.

Responding to the public calls for investment in hydropower companies, many have invested their hard-earned savings in IPOs. Though the provision for companies to allot 10 percent equity shares to locals had been introduced with good intentions, it turned out to be a nightmare for many.

Lata Devi Bhattarai Paudel, a resident of Putalisadak, Kathmandu, also regrets investing in hydropower stocks. From 2010 to 2015, she had queued up for hours to apply for IPOs of difvarious hydropower companies but has gained nothing. She has instead suffered losses worth about Rs 10,000.

The market value of the stocks of seven hydropower companies — Universal Power Company Ltd, Kalika Power Ltd, Mountain Hydro Nepal Limited, Panchakanya Mai Hydropower Ltd, Rairang Hydropower Development Company Ltd, Chhyangdi Hydropower Ltd —she owns are less than the face value. Her Rs 50,000 investment in those companies is now worth less than Rs 40,000.

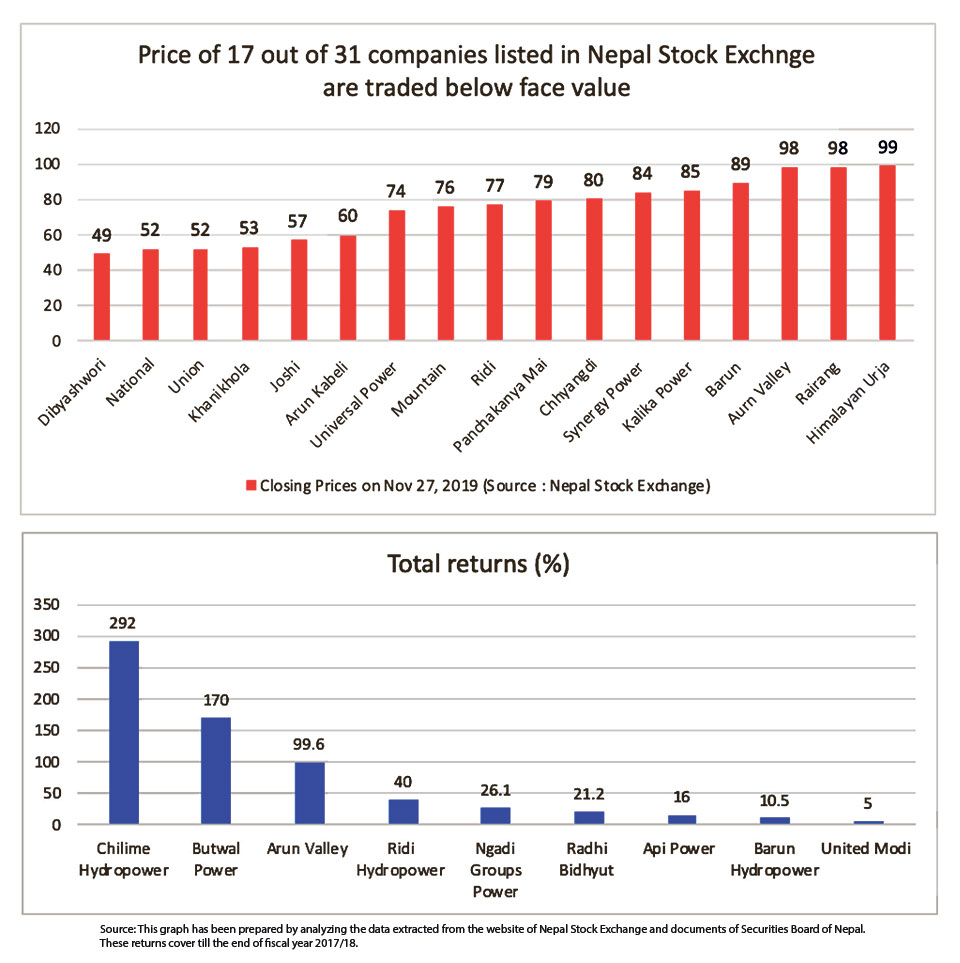

The story of KKHC is not unique. Seventeen (see graph) out of the 31 hydropower companies listed at Nepal Stock Exchange have failed to pay any dividends to their shareholders. The market price of all these companies is below the face value or the amount they invested while buying the IPOs.

Most of these IPOs were oversubscribed, by over a dozen times, when floated in 2015 and 2016. Now, nobody is interested in investing their money in hydro stocks.

Even the media reported the stories on these IPOs without deeper analysis of the companies and their projects. Energy ministers repeatedly asked people to invest in those stocks without considering profitability. Minister for Energy Barshaman Pun last year stated that those who own hydropower shares may find good brides. “All these statements are misleading and have proven costly to many people like me because they are making us poorer instead of helping us become rich. We have been betrayed,” Paudel said.

The rush for started with the success of Chilime Hydropower Company Limited, which was given a favorable electricity price by the NEA. According to a study titled “Local Shares: An in-depth examination of opportunities and risks for local communities seeking to invest in Nepal’s hydropower projects”, commissioned by International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Australian Aid in 2018, local communities who invested in hydropower shares expected lucrative gains like many shareholders of Chilime, but the lack of financial literacy among the investors coupled with the lack of governance in the sector posed high risks.

Chilime, whose electricity was given higher price rates by the NEA because the NEA staffers themselves were investors in the company, has already distributed 292 percent dividends — 117 percent cash and 175 percent bonus dividends.

The number of applicants subscribing for hydropower shares has gone down dramatically over the past one and a half years, mainly due to the oversupply of shares. However, the government in May last year promoted the idea of investing in hydropower in its flagship initiative called the ‘People’s Hydropower Program’ and asked commoners to pour their money in Trishuli Jal Vidhyut Company Limited, which is building the 37 MW Upper Trishuli 3B Hydropower Project. But the people have not been informed about the possible risks associated with the shares.

The IPOs allotted for locals have gone under-subscribed and the general public’s craze for subscriptions has dwindled, according to applications received on IPO floated in recent years.

The government has tricked people into oversubscription by allowing the company (under the flagship program) to issue IPO without a third-party rating, which is mandatory for all other private companies, according to critics. “Commoners are deprived of their right to know about the financial health of the company. Therefore, their investment is at risk,” said Kumar Pandey, vice-president of the Independent Power Producers Association, Nepal.

Pandey acknowledged that shareholders were not earning as shown by the balance sheet of most hydropower companies except Chilime and Butwal Power Company.

Pandey, who is also the chairman of the National Hydropower Company (NHPC), blamed the ever-increasing cost of hydropower projects to the lack of profits on hydropower shares.

The NHPC, which has been running the 7.5 MW Indrawati III project since 1999, has not paid its shareholders even a single penny as dividend for over a decade, mainly due to lack of good governance in the company. Pandey said, “We are suffering heavy losses after the government inadvertently terminated the license of the Lower Indrawati project.”

But experts and investors disagree with Pandey. According to them, the hydropower companies hide their costs until the issuance of IPOs, which is in fact much higher than shown on their documents. Moreover, the promoters do not really invest the amount they commit; rather they inflate the project and adjust their investments in that inflated amount.

Chhote Lal Rauniyar, vice-president of Nepal Investors Forum (NIF), said costs are inflated by 20 percent to 60 percent. Normally, the cost of the construction of hydropower is calculated at Rs 150 million per megawatt (MW), but this price is heavily inflated to help promoters pocket a hefty sum by the time the project is completed.

“Only a few hydropower companies are paying dividends. Many have nothing to distribute although the projects are operating normally because promoters have gotten their projects financed from the banks at inflated costs. And inflated costs have eaten into the profits that the investors would get,” explained Rauniyar. He, however, did not specify the

names of the companies involved in such wrongdoings.

The NIF and other professional bodies of investors have put pressure on the Electricity Regulatory Commission (ERC), the regulator in the hydroelectricity sector, to control these anomalies. The ERC started its work in June this year. “The regulator should check bogus companies entering the sector and protect IPO investors who are mostly housewives, students, civil servants, and low-income people,” said Rauniyar.

Rauniyar suggested most hydropower developers exaggerate progress in their project works. He claimed that most such developers try to show, by posting fake figures, that half of their work has already been completed. The Security Board of Nepal (SEBON) allows the company to issue IPO, according to him. “The developers and the SEBON collude to cheat people in investing in those fake projects,” he said.

A 2018 report on local shares also suggests a need for better regulation of the sector, among other things. The report says, “The best way to engage local communities is by increasing their understanding of how the capital market works and the fundamentals of the hydropower company in which they are about to invest. Effective regulation of the hydropower companies by the recently established Electricity Regulatory Commission is also needed.”

Director-General of the Department of Electricity Development, Nabin Raj Singh, admitted that the hydropower companies were not earning a profit, with investors getting zero or paltry dividends because of the problem surrounding the cash flows of the companies. “Their cash flows have been hit by the variation in river flows, which is caused by climate change,” he said. Singh, however, said the government was aware of the problem faced by small-scale hydropower projects and was set to decide on this issue in the near future.

About a million people have poured in

Rs 5.18 billion in the 456 MW Upper Tamakoshi (which is expected to start power generation next year after delays of four years and near-double cost overrun). When the project was launched, it was regarded as a highly lucrative investment. Delay in the project by just one year in FY 2018/19 has alone incurred a cost overrun of about Rs 20 billion taking the project’s cost to Rs 69 billion. The cost overrun was caused by several issues including interest on loan, loss of income, damage caused by the 2015 earthquakes and the Indian blockade. The estimated cost of the project in 2011 was Rs 35.29 billion (excluding bank interests). These delays are eating into the profits of shareholders.

Arjun Gautam, a chartered accountant at the Employees Provident Fund, which has financed Rs 10 billion in Upper Tamakoshi, said, “The project’s internal rate of return on equity was set at 15 percent, but the IRR has now declined to 12 because the cost of the project has also gone up with the interest amount of interest on loans, loss of income and the project license period gradually getting shorter.” The project has 35 years of license, which expires in 2055 AD.

Many investors do not know why they are losing money even on the IPOs, which were regarded as the safest portfolios for people. Poor farmers in Bhattedanda didn’t have any idea why they were not getting returns. Kulman Ghising, NEA’s managing director, said the price NEA has been paying to private companies covers about 17 percent rate of return on an average. To put it simply, an investment of Rs 100 in hydropower companies fetches Rs 17 annually on average. This average return may vary, but no return for several years means the projects are cheating the ordinary shareholders, according to Ghising.

No companies except for Chilime and Butwal Power Company have distributed a minimum 17 percent dividends in any year. NEA favored Chilime project in electricity price while Butwal Power Company got all its financing through Norwegian grants in its major power plants--Adhikhola and Jhimruk. Both promoters and general shareholders also get an equal percentage of returns. Experts ask why promoters are building power plants if there are no returns.

Deepesh K Vaidya, managing director and founder of Kriti Capital and Investment Limited, investment management and consulting firm, says it is difficult to answer the question. “This is because there is no policy of paying for efficient management and this has forced hydropower developers to opt for secret ways to extract benefits,” he said.

Longer payback period and long gestation period, lack of good management and high investment costs are the reasons behind the failure to lure investors to the sector, Vaidya said.

Despite such dismal performance of hydropower projects, the government has initiated the ‘People’s Hydropower Program,’ and intends to collect Rs 100 billion from the general public over the next five years. The government has set 21 projects in line for the purpose and the projects are supposed to generate 3,500 MW in total.

Moreover, there are several private companies eyeing the public’s coffers.

“No matter what the government and private companies offer, people know that investment in hydropower is a risky business,” said Rauniyar. Experts suggest that the government should come up with strategies to minimize risks of the investments through proper regulation by the commission. Guru Prasad Gautam, Syangten’s neighbor, is tired of paying interest on the loan borrowed to invest in shares. “We will no longer throw hard-earned money into the river (hydropower stocks),” Gautam said, adding that he has already learned his lessons from the Khanikhola Hydropower Project.

This story was written under the investigative reporting fellowship offered by Media Foundation, with support from Humanity United.

You May Like This

Humla deprived of electricity following damages to hydel project

KATHMANDU, Sept 26: Floods following incessant rain have damaged the Ridham Small Hydropower Project in Humla district of Nepal. The... Read More...

2 missing, hydropower projects damaged in Sidhuopalchwok due to incessant rain

SINDHUPALCHWOK, July 8: Two construction workers went missing while two others sustained injuries due to floods triggered by incessant rainfall in... Read More...

Upper Tamakoshi to complete by 2019-end

KATHMANDU, Jan 23: Works of Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project (456 MW) will be complete by the end of 2019 if... Read More...

Just In

- Indians vote in the first phase of the world’s largest election as Modi seeks a third term

- Kushal Dixit selected for London Marathon

- Nepal faces Hong Kong today for ACC Emerging Teams Asia Cup

- 286 new industries registered in Nepal in first nine months of current FY, attracting Rs 165 billion investment

- UML's National Convention Representatives Council meeting today

- Gandaki Province CM assigns ministerial portfolios to Hari Bahadur Chuman and Deepak Manange

- 352 climbers obtain permits to ascend Mount Everest this season

- 16 candidates shortlisted for CEO position at Nepal Tourism Board

_20220508065243.jpg)

Leave A Comment