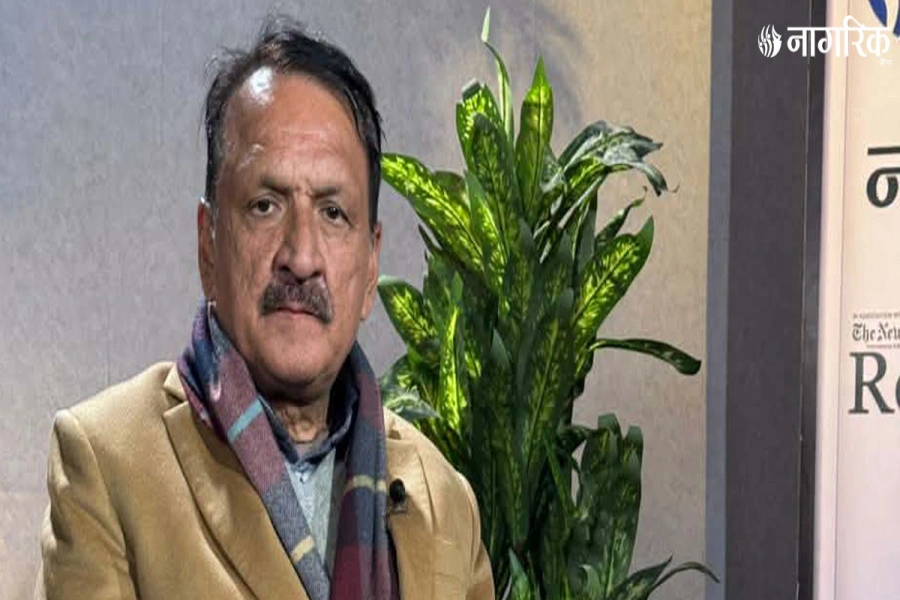

UCPN (Maoist) chief Pushpa Kamal Dahal is the most important actor in Nepali politics, but he is perhaps also the most reviled. The country’s future political course largely depends on him, no matter how much he is hated among the political class.

Detractors call him the master of doublespeak with art of fooling people with empty rhetoric. He has been called the depraved alter ego of Chanakya who taught his disciples when to shed crocodile tears and when to put up a beguiling smile. The erstwhile rebel leader is also held responsible for over 17,000 unnecessary deaths. At the same time, his political opponents acknowledge his ability to influence people like no other leader. Sher Bahadur Deuba once told this scribe that Dahal can successfully present truth as untruth and vice versa. [break]

Apparently, Dahal boasts many qualities that his rivals lack. He is a convincing orator with charismatic look. In an opinion poll carried out among beautiful Kollywood divas few years back, most gave Dahal the title of the most handsome and presentable leader. No wonder Kollywood beauty Rekha Thapa fell for his charms and joined his party recently.

On the political front, he knows who to invoke to take his opponents into confidence. He professes to being the faithful disciple of Nepali Congress founding father BP Koirala while addressing NC gatherings. He does not hesitate to call Madan Bhandari his inspiration when he has to placate the CPN-UML cohort. But none of these maneuverings are going to help him in the long run. Dahal knows this better than anyone else.

Early this month he made public his three mistakes of post-2008 politics. He confessed that denying presidential berth to late Girija Prasad Koirala, sacking then Army Chief Rookmangud Katawal and hesitating to settle the dispute over state restructuring were the “mistakes that I now regret.” He reiterated on Monday that he is responsible for CA’s failure to draft constitution. Only Dahal can tell how honest he is in this confession. But many believe politics would have taken a different course if he had not committed those mistakes.

For instance, if he had allowed Koirala to become the first president, NC and UCPN (Maoist) could have worked together to settle contentious constitutional disputes. If he had not sacked Katawal, he would have remained Prime Minister for longer and if he had helped put contentious issues to vote, the country would perhaps have a new constitution with a two-third majority. Why has the Maoist supremo taken to the politics of confession on election eve, potentially jeopardizing his political career?

There are three main reasons. First, Maoist supporters have been deeply disillusioned by his leadership.

He has lost his stranglehold in the party. Owing to intense internal disputes, he had to take power into his own hands to prevent the situation from going out of control. Following the split of Mohan Baidya faction in June 2012, most committed ‘revolutionary’ cadres have defected to Baidya camp. Besides, his perennial flip-flops on ethnic issues, ethnic identity-based federalism in particular, has betrayed the hopes of ethnic communities who used to consider him their trusted guardian. In this situation, he is not going to be able to maintain the same hold on politics with the same old rhetoric. So he has been trying to impress on cadres that he is responsible for the current state of affairs but that he deserves one more chance to right the wrongs. Dahal’s situation is similar to that of NC and UML leaders in 2002.

Following King Gyanendra’s coup, NC and UML launched street protests to press the king to restore the parliament. But people did not join their protests. Only when the leadership began to confess of their past sins at Ratanapark and promised not to betray people’s trust again did the public give them the benefit of doubt. If not, perhaps their anti-monarchy campaign would have taken few more years to gain traction.

Second, Dahal knows well that his party’s sweeping victory in the last CA polls was partly the result of huge support from deeply dissatisfied UML and NC supporters who saw Maoist party as a viable alternative. But his antics in past few years have betrayed their trust. Preliminary evaluation by Maoist leaders, mobilized in all 240 electoral constituencies, has shown that the party’s grip has eroded at the local level and that its chance of once again emerging the biggest party in the upcoming polls is slim. Dahal has no way of steadying the boat other than by making sure Maoist sympathizers among NC and UML—who silently support the cause of Maoist revolt but abhor the violent means—that they can still rely on him.

Third, after five years of active politics, he has no option but to confess to his political crimes. One may expect him to confess, in one way or the other, that ten year-old people’s war was a mistake. Dahal won’t be making this confession any time soon for the fear of completely disillusioning his cadres. But it is possible that sometime in the future his party will take a formal decision toward this end. History suggests the same. A group of Nepali communists under East Koshi Coordination Committee (then led by Manamohan Adhikary) launched a violent movement in Jhapa to eliminate “class enemies” in 1967. In 1974, the leaders (most of whom are active UML members now) endorsed through the party (then ML) convention that Jhapa Uprising was a mistake.

In a way, one could say UCPN (Maoist) has already made a similar confession, for instance through their last general convention. Dahal put the party on the path of multiparty parliamentary practice and open market capitalism. So much so that Maoist ideologue Baburam Bhattarai has ruled out the possibility of ethnic-identity based federalism, once his idée fixe, bringing the party even closer to NC and UML. Besides, Dahal has been insisting that there should be election in November, even if it might not be conducive for the party. The realization that violent revolution was misguided is the driving force in this paradigm shift in the once radical communist party.

What torments Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) is not the possibility of his murder of a pawnbroker being discovered. He has destroyed all evidence. But the sense of guilt so torments him that he will go insane unless he confesses to his crimes. The major theme of all confession literature is that committing crimes is not as hard as bottling up guilt feelings. There is no exact parallel between Raskolnikov and Dahal. But in his existential angst the real Dahal is no better than the fictional Raskolnikov. Such a confession may not make him the most popular leader but it will certainly make him seem more human and help him become a better, humbler leader.

mbpoudyal@yahoo.com

UN probe accuses Israel of crimes against humanity, Hamas of wa...