OR

Opinion

Can Nepal Avoid the Debt Trap?

Published On: December 17, 2022 08:00 AM NPT By: Hari Prasad Shrestha

More from Author

- Why Federalism has Become Risky for Nepalese Democracy

- Hunger is a Serious Problem in South Asia

- Tourism Can Be A Catalyst For Change in Karnali Province

- Nepal’s Southern Border Has Become An Open Regional Crossroads

- Opening a new gateway for Kailash Mansarovar Yatra through Nepalgunj-GunshaNagari flight

Many of the so-called ‘projects of national pride’ are being executed through foreign assistance with considerable loan amounts. All these projects are important, however, there are abnormal cost increases in most projects due to unending deadline extensions and low rates of return have increased Nepal’s debt burden. The Melamchi Drinking Water Project, Pokhara Regional International Airport, and Sikta and Babai irrigation projects are some examples of high-debt burdens.

Many policymakers and economic experts in Nepal express their complacency that the debt ratio to the gross domestic product is among the lowest in Nepal compared to other countries of South Asia. Usually they compare Nepal with Sri Lanka and blatantly conclude - Nepal may not be in an economic crisis.

However, the truth is it is hardly analyzed whether the achievements made by programs and projects executed through debts - external as well as internal - are at an acceptable level or only the debts are piling up without any signs of positive transformations and better support for the poor and marginalized population.

Moreover, when the country is not in a position to collect enough revenue for its recurrent expenditures, it would certainly be a challenge to manage resources for the mounting debt servicing payments in the years to come. Moreover, irrelevant and unproductive expenditures are expanding like a pandemic with the improper use of the scarce resources. These are signals that Nepal is advancing toward a situation of debt trap.

A debt trap is when a country spends excessively more than it earns and borrows more than its capacity and spends in unproductive and needless sectors.

Brahma Chellaney, a professor of strategic studies at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, coined the term debt-trap diplomacy to describe how the Chinese government leverages the debt burden of smaller countries for geopolitical ends.

He saw ‘debt trap diplomacy’ in China’s handling of Sri Lanka’s debt distress by taking over its Hambantota port on a long-term lease. The thesis caught on and began to be used widely, becoming “something approaching conventional wisdom”, especially in Washington DC. Other scholars have disputed the assessment, arguing that Chinese finance was not the source of Sri Lanka’s financial distress and it has also been applied to the International Monetary Fund (IMF); both allegations, however, are disputed.

Both the IMF and the World Bank have also been accused of predatory lending practices to keep emerging economies in debt, including demanding structural adjustment programs as a condition for loans, often to governments who see these loans as a last resort, pressuring for privatization and undue influence over central banks. The Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt wrote: “The [World Bank] and the IMF have systematically made loans to States as a means of influencing their policies.” The IMF has used geopolitical considerations, rather than exclusively economic conditions, to decide which countries received loans.

Debt can boost economic activity, only if poor countries invest in new capital or productive sectors that yield returns higher than the cost of borrowing. But much borrowing goes simply to finance consumption spending and on projects of low rate of return above income on a persistent basis — and that is a recipe for bankruptcy.

In Nepal, there are 21 projects of national pride in different sectors -road, irrigation, hydropower, international airport, religious site, railway, drinking water and conservation. Many of these projects are being executed through foreign assistance with considerable loan amounts.

All these projects are important, however, there are abnormal costs increase in most projects due to unending deadline extensions and a low rate of return has increased the debt burden of Nepal. The Melamchi Drinking Water Project, Pokhara Regional International Airport, Sikta and Babai irrigation projects are some examples of high debt burdens.

The projects of national pride could have also included more prioritized mega and sophisticated projects, which could have brought real change in the national economy and development with a high rate of return by enabling the government to repay the debt amount in time. Apart from the projects of national pride, many sectoral projects financed by loans are also facing similar issues of debt burden.

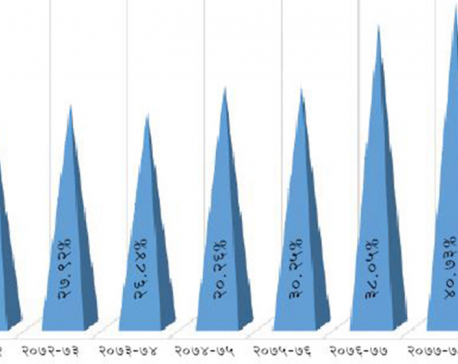

According to the Public Debt Management Office of Nepal, the total government debt reached NPR 2,011.95 billion at the end of the 4th quarter of F/Y 2078/79 (July 16, 2022). Out of this amount, the external debt is NPR 1025.84 billion and internal debt consists NPR 986.10 billion. The total outstanding debt of the Government of Nepal for the 4th quarter of F/Y 2078/79 has increased by 8.65 percent during the period. External debt has increased by 5.47 percent and internal debt by 12.16 percent.

At the end of the 4th quarter of FY 2078/79, the total debt to GDP ratio was 41.47 percent whereas the external debt to GDP ratio was 21.14 percent and for internal debt to GDP, the ratio was 20.32 percent. During the third quarter of FY 2078/79 (Chaitra 30), the debt to GDP ratio was 38.16 percent consisting of 20.04 percent on external debt and 18.12 percent on internal debt.

Nepal received the highest loans from the International Development Association, followed by the Asian Development Bank. Among the bilateral donors, Japan is the largest creditor to Nepal. The debts owed to China are basically loans from the Export-Import Bank of China for various development projects. India is the next bilateral creditors after China.

Nepal’s reliance on external as well as internal debts are proportionally high compared to its performances and capacity to repay. And for a small economy like Nepal it may not be safe to solely rely heavily on debts.

As a result of high dependency on external debts many countries in Sub Saharan Africa and South Asia are encountering the difficulties of debt traps. For example, Sri Lanka is unable to pay excess loans received from China and Bhutan is also under severe pressure as it accepted Indian loans to construct hydropower projects more than its capacity to repay.

Recently, Bhutan’s Prime Minister’s Office in its official Twitter account indicated its financial adversity - @PMBhutan “The amount we pay for electricity imports evens out the revenue we generate. This is our reality. How much can we depend on hydro as an economic sector?”

Nepal also must be careful, alert and well prepared on how to avoid possible surprise shocks of debt traps. First of all, the fiscal and financial systems and subsystems must be in order, balanced and disciplined to bring the economy on the right track.

For this, Nepal must improve its tax system and tax collection by controlling abnormal tax evasion and unauthorized trades to reduce the need for borrowing.

As Nepal’s capacity for debt management remains weak, it needs careful management of the opportunities, costs and risks of different sources of borrowing.

Nepal lacks transparency in its overall debt management and without greater transparency, it could face the real debt risks. There is considerable room for improvement in debt transparency in Nepal. The public disclosure of lending contracts would allow parliament, journalists, and civil society organizations to examine them, and would also allow other lenders to have the full information before making further loans. Therefore, from project formation till debt negotiation - at all stages - Nepal needs strong homework with greater transparency.

It must be our mind that both debt recipients and donors must be equally responsible for the debt crisis in poor countries. Preventing widespread low-income country debt crises is not solely the responsibility of the borrowing countries: it will require serious changes on the part of the creditors and the international system for fair support and write-off of unproductive loans.

Nepal must be capable of responding to improper pressures of donors by accepting loans haphazardly by becoming a begging bowl without proper assessment of projects and conditionalities of loans.

Ultimately it is the responsibility of Nepal to take greater competency for the evaluation of potential projects to ensure their viability and financial sustainability. It must develop its own ability to bargain with development partners to ascertain that people must benefit from the projects and debt must be utilized for economic growth and increased revenue generation to repay it comfortably.

You May Like This

Nepal has public debt of over Rs 2 trillion

KATHMANDU, March 7 :The country's public debt is increasing every year. By mid-February of the current fiscal year (FY 2022/23),... Read More...

Swargadwari airport construction plan unveils

PYUTHAN, Sept 24: A plan with an estimated cost of Rs 770 million was unveiled for the construction of Swargadwari... Read More...

Quality improvement in country's economy: growth estimated to be seven per cent

KATHMANDU, May 28: The Government has estimated the economic growth of the current fiscal year to increase by 6.94 per... Read More...

Just In

- Youth found dead in a hotel in Janakpur

- CM Kandel to expand cabinet in Karnali province, Pariyar from Maoist Center to become minister without portfolio

- Storm likely to occur in Terai, weather to remain clear in remaining regions

- Prez Paudel solicits Qatar’s investment in Nepal’s water resources, agriculture and tourism sectors

- Fire destroys 700 hectares forest area in Myagdi

- Three youths awarded 'Creators Champions'

- King of Qatar to hold meeting with PM Dahal, preparations underway to sign six bilateral agreements

- Nepal's Seismic Struggle and Ongoing Recovery Dynamics

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment