What kept Nepal poor and how can we become a wealth-creating nation?

Milan Jung Katwal

Nepal has never been a wealthy nation. I often ponder on what kept us poor; if we can ever be rich, and if so, then how? The most obvious reasons for our economic backwardness include the limitations of geography, such as small territory, mountainous topography, and landlockedness. The narrative is comforting as it makes poverty feel inevitable. But in my view, the excuse is as dishonest as incomplete. I believe that we have been a victim of poor policy choices, heavy state control, and politicized redistribution that have stifled the very forces that yield prosperity elsewhere: private enterprise, capital formation, and competitive markets.

The fact that we have never truly aimed to become a wealthy nation may be one of the sincere reasons why Nepal has remained poor. We have aspired to become a happy nation, or a peaceful nation, or something similarly abstract, but never rich. Being rich is often regarded as filth or a sin, and wealth creation is neither celebrated nor encouraged. As a society, we prefer fixed deposit savings over business investments. We unanimously accept accumulating gold as a wiser financial bet than investing in groundbreaking ideas or startups and businesses of our friends and families. We have been ridiculously pessimistic and unambitious as a society when it comes to wealth creation. This very mindset is well reflected even in our national plans, policies, and objectives. Therefore, the first step towards making Nepal rich would be to implant this optimism and ambition into our national mindset that we can be a high-income country; we can be rich.

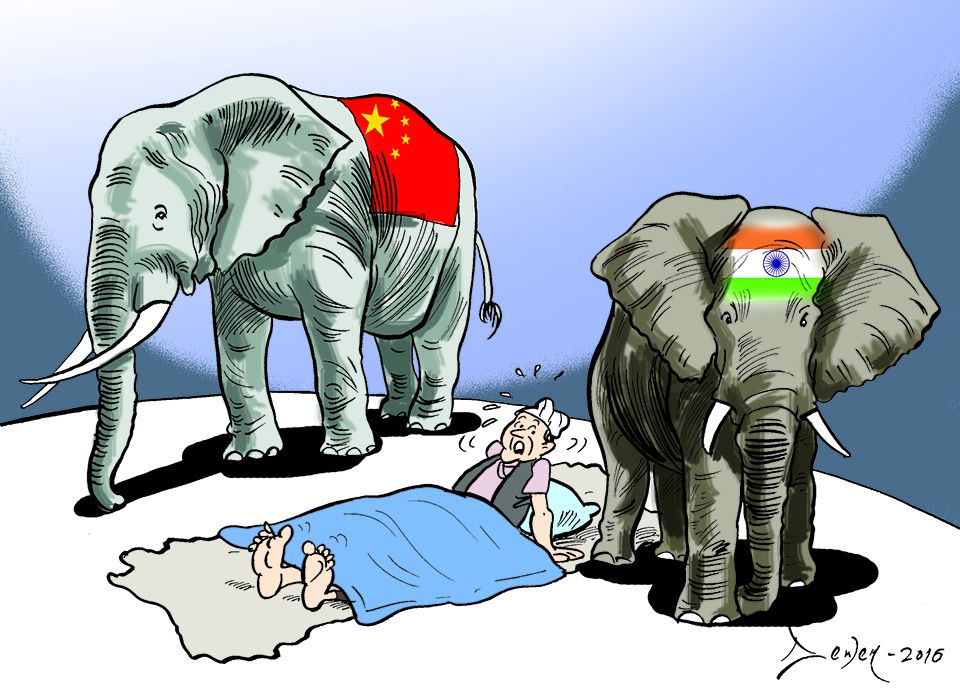

Mao’s shadow and a permanent socialist bench

Madhesh’s poor struggling to survive winter

Nepal’s statist instincts are not accidental; they are ideological. The communist parties of Nepal that draw inspiration from Mao Zedong and his strategy of class struggle have dominated Nepali politics for a long time. The dominant left carries the idea that economic progress flows from state action and redistribution rather than from private risk-taking and entrepreneurship. The governments stemming from this thought process pose a tendency to control both political and economic powers and therefore risk the full capture of state powers and authoritarian rise. The role of governments should be to facilitate, not to provide. By relying on the government to provide for us, we are not only giving the government more authority but also weakening ourselves, which runs contrary to the essence of democracy.

Milton Friedman had famously said that a society that demands equality before freedom neither gets freedom nor equality. The thought quite resonates with the current socio-economic status quo of Nepal, where communist driven narratives demand an “equal pie” out of a nearly non-existent pie. Our policy debates are focused on how to divide the economic pie instead of how to expand it. If only we focused on expanding the pie first, everyone could be better off in the long run. The communist driven narratives, over decades, have led the majority to believe that our “pie is fixed” and someone can only gain at the cost of others. This is exactly why most people associate wealth with sin and poverty with virtue. We must wake up to realize that the lack of capital formation and expansion has limited our financial and economic freedom, and therefore, our political freedom also remains limited.

Even social democratic parties like the Nepali Congress, historically a counterweight to communist parties, have failed to articulate a coherent pro-market vision that bolsters the private sector. The politicians have often treated the private sector as a patronage base rather than a partner in growth. Entrepreneurs and businesses have no moral backing from pro-capital political forces. Instead, we see a growing number of “businessmen-politicians” who use politics to protect their own interests, not to build the institutional foundations for a free and fair market.

Article 4(1) of the Constitution defines the State of Nepal as “a socialism-oriented” state. It enshrines the state’s responsibilities for social justice and welfare. While these promises are morally legitimate and reflect our democratic struggle, lofty promises and fiscal priorities are intended toward short-term handouts rather than the support infrastructure and institutions that unlock productivity. The short-sighted vision has pushed us into a vicious cycle where the best and the brightest of our human resources leave for foreign labor markets, and the domestic firms remain unexpanded and undercapitalized.

The Cost of Statism: Remittances, Unemployment, Shallow Capital Markets

Statism has had a high cost on our lives and the economy, and the economic outcomes speak for themselves. Personal remittances account for nearly one-third of Nepal’s GDP, one of the highest ratios in the world. While the inflow has supported a rise in the living standards of the people, growth in imports and consumption without any long-term investments in the productive sectors leaves the economy vulnerable.

Our capital markets remain shallow. The stock exchange, NEPSE, has grown but remains dominated by a few sectors. It lacks the depth to finance major industrial or infrastructure expansions, and is rather plagued by allegations of insider trading, manipulation, and irregularities. Nepal’s economy is stuck in a low-productivity equilibrium with a large proportion of the informal sector, small firms, heavy reliance on imports, and little technological upgrading. Statist traits exacerbate the trap by rewarding favoritism over competition and short-term political visibility over long-term gains.

From Low-Income Trap to High-Income Future

I firmly believe that Nepal can escape the current low-income trap and achieve a high-income future. There is no silver bullet strategy, and I also agree that markets are not a panacea, but learning from the global economic history suggests to us that countries have successfully moved from poverty to prosperity within a single generation, and I refuse to accept that the story would not be replicable for Nepal.

Consider South Korea, Singapore, Botswana, Vietnam, or Mauritius. All were poor before they began economic liberalization, export-oriented private investment, strengthening capital markets, and heavy investment in human capital. However, the market reforms were also complemented by good governance, strong institutions, the rule of law, and targeted social safety nets. Nepal can do the same: industrialization, adopting market-friendly models in addition to institutional reforms for sustained progress.

Nepal has tremendous potential in the hydropower and tourism sectors. Preparing skilled human resources in technology and commercializing agriculture will be equally important. To transform our potential into exports, we will require private financing, reliable property rights, regulatory predictability, and an improved ease of doing business. A deeper capital market and strategic Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) could allow us to mobilize our household savings and remittances, now spent mostly on imports or parked unproductive assets, into long-term, sustainable, and secure investments at home. While the government and the private sector must work hand in hand to create wealth, they have their own strengths and limitations. The state can set rules, build infrastructure, and provide safety nets, but it cannot sustainably employ everyone. Therefore, the function of the state is to maintain the confidence of the private sector while innovation and private risk-taking drive the economy.

(The author is the founder of the National Policy Forum (NPF). Tweets @MilanJKatuwal)