True, it’s difficult to find a good paan stall in New York. Even more difficult, however, is to find a paan stall run by someone from Nepal. That particular evening I and Ahmed were ambling through the streets of Queens. It was early October and, though at least forty more sunsets were yet to unfold before the first snow, there already was a certain whiff of wintry sadness in the wind. Partly because of this wind and partly because of an inexplicable longing that held sway over my heart, I felt tempted to ask Ahmed if we could launch another search for a Nepali paan shop. To be honest, on other occasions I would have given free rein to this desire, but this time I decided to resist it with full force. After all, only a week ago we had wasted hours on this effort which had, it is true, annoyed Ahmed. Besides, both of us had recently broken up with our college sweethearts and Ahmed had particularly taken it hard on himself. Which is why I didn’t want to bring up something that would further distress him. In fact, from the tensed muscles of his face and his sad, insomniac eyes I could tell he was still brooding over the memories of his time with Noori.

As we walked past the Travers Park Ahmed stretched his arms sideways, muttered something to himself and then surprised me with his loud, metallic voice, “Finally bro, I feel so free. Yeah man, like a bird. You know what I mean.” Inhaling deep he continued in that same excited manner, “I know why you’re looking at me like that. I don’t deny that only yesterday I was complaining about how I missed Noori. But now, bro, I’m glad. Seriously bro, life is to be free, to be single, man.”

“Things happen for good,” I said, and suddenly began to doubt my words. In response to this realization I felt an itching impulse to add something impressive but before I could do that Ahmed said, “I bet bro, I bet. That’s the beauty of life, things happen for our own good. Anyways, should we go to a Nepali restaurant and get some momo? Or do you want to try some Bengali food? Um, Bengali Rosmalai, what you say? Come on bro, you’ll like it.”

Of course, I wanted to go to a Nepali restaurant, if not to guzzle momo, then in any case, for the hope of finding someone with whom I could initiate a warm conversation about Nepal. However, since Ahmed was imploring me so vehemently and, besides, last time we had already visited a Nepali cuisine, out of courtesy I decided in the favor of Bengali food. “Sure, Rosmalai sounds like something,” I said. “We should also try some Calcutta biryani.”

“With mango pickle too!” exclaimed Ahmed. “They have local Indian pickles these days.”

“By the way which Bengali restaurant are we planning to go?” I asked and glanced at the dark-haired lady in a pink jacket who swished past, leaving a mystery of jasmine aroma in the air. “We should not go to the one we went to on your birthday. They didn’t have good biryani, you know. On top of that the waiters were awful. I mean they acted so arrogantly, those swines.”

“No worries, bro. This time I’ll take you to my favorite place.”

“Sounds good,” I said and found my eyes, which until then had been drawn by the lady in a pink jacket, staring at a gloomily lit paan stall. On a more concentrated gaze an old man with greyish strands of hair peering out of his Dhaka-Topi took shape with such clarity that I felt, despite the indigenous greyness of Jackson Height, as if I were in the tropical atmosphere of Nepal. A wave of nostalgia took over me. I nudged Ahmed and pointed in the direction of the stall. “Isn’t that man’s hat Nepali, bro?” Ahmed asked. “I bet bro, I bet. Let’s go,” he then mumbled, nearly dragging me along as we walked across the street.

“Two paan for us please,” Ahmed ordered as we stood by the stall.

“Hard type, sweet type?” the old man asked, nibbling his lower lip.

“Hard,” Ahmed replied and lit the cigarette that he had pressed between his lips. “With some extra touch of clove and tobacco.”

The old man nodded.

Heart to Heart with Malvika

“Jackson is quieter than usual today,” I said.

“It don’t getting noisier now,” the old man said. “It getting noisier later.” He opened the container of Catechu paste and began to stir with a tiny spatula.

“That makes sense,” I said. “Isn’t that Nepali Dhaka-Topi, that cap you are wearing?” He continued to stir the paste mechanically, completely oblivious to my question as if he had not heard me at all. So I leaned towards him and added in a louder voice, “Are you from Nepal?”

“Myself?” He watched me with an uncertain smile.

“You look like a Nepali. So I asked.”

“Myself Nepali, yeah yeah. Myself coming here after the earthquake. Yourself also from Nepal?”

“Yes, I’m from Kathmandu.”

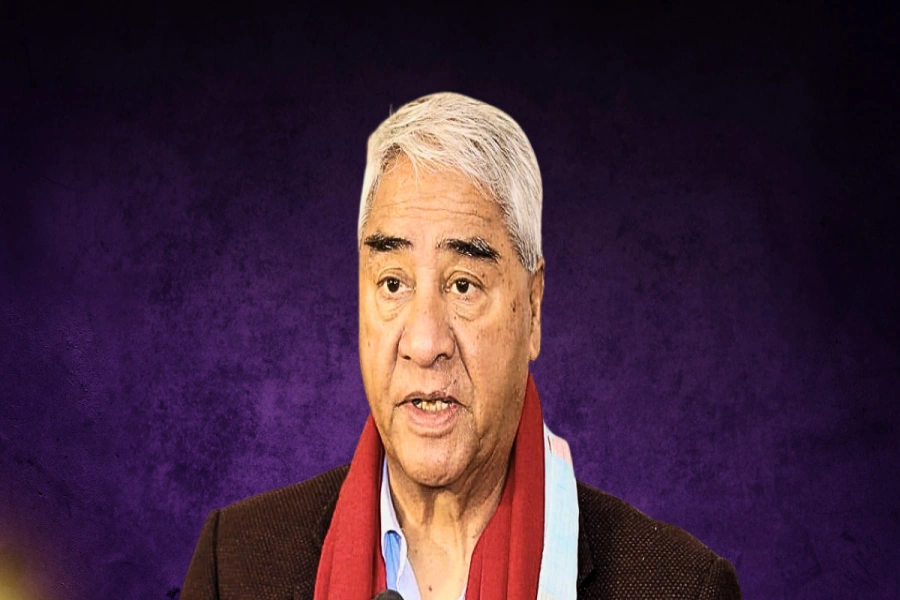

“Kathmandu, Kathmandu,” he mumbled to himself as if savoring the sound of it, as if this sound reminded him of something beautiful from the distant past. “Myself Butwal,” his voice was filled with the buoyancy that comes naturally when one has convinced himself that he can now trust his new acquaintance. “One minute,” he rose while arranging the Dhaka-Topi with the back of his wrist. From a refrigerator’s top he picked up his iPhone and spoke into its speaker, “Siri, play favorite song.” The old Hindi music, which was till then humming away in the background, was now replaced by the nostalgia-evoking song of Nepathya as the voice of Amrit Gurung took over: “Jiwan ho ghaam Chhaya”: Life is sunshine and shadow. As he sat down again, his eyes were shining as if in response to the memories evoked by this song. Smiling affectionately, he said, “Myself Rabindra Gautam,” then he whispered in Nepali, “We could talk in Nepali but that would be awkward for your friend.”

“It’s alright for us whichever way you talk,” I assured him. “Anyways, I’m Swarnim. And he is my friend, Ahmed.”

“Ahmed,” my friend introduced himself, letting out a cloud of cigarette smoke from his mouth. “I’ve come here several times but saw your stall only today, man. In fact, I grew up here in Queens.”

“Not mind,” Rabindra Baje said. “Weself starting this paan shop only few weeks ago.”

“How has the business been going?” Ahmed asked.

“Fine, fine,” Baje replied. “Sometime good customers coming. Sometime don’t coming. But fine, fine.”

“I see.”

“I living alone here,” Baje said, looking entreatingly at me out of his tender, wistful eyes. “My son doing married and living in Texas. He coming sometime to meeting me.” His hands were shaking as he folded two betel leaves with their corresponding contents and held them out towards me. I gestured to Ahmed to take the first and then I accepted the other one.

“It’s good, man,” Ahmed mumbled immediately after shoving the paan into his mouth. “Real good one.”

“You like it,” Baje smiled timidly.

“Baje, why have you not brought your wife to America? Don’t you think she’ll like it?” I asked, directing the content of the paan towards my left cheek so that I would sound as lucid as possible.

He cleared his throat and wiped his paan-stained hand on a rag. The veins on his throat strained as if he were about to speak, but instead he let out a sigh that disappeared forlornly under the dusky sky. He took his iPhone in hand. Only then did I realize that the song of Nepathya had already ended and once again some old Hindi music was drifting softly out of the speaker. Baje whispered into the phone, “Siri, play Jhareko Paat Jhai Bhayo, ujaad mero jindagi, Narayan Gopal”: My life has become dreary like a fallen leaf, Narayan Gopal. As the air pulsed with the melodious voice of the singer, an overwhelming sense of grief seemed to descend not only on Baje’s heart but also on the whole of New York. “You like America?” Baje’s voice reached me.

“I don’t know,” replied I. “Sometimes I like it. Sometimes I feel scared.”

“When I coming here first,” Baje’s voice quivered with emotion. “Everything good. My wife happy, happy. A year later my son and his wife coming. But they going Texas soon.” He paused, nibbling his lip, and looked at me, then at Ahmed, who was quietly chewing paan and listening to our conversation. White strands of smoke were spiraling serenely out of the butt of the cigarette that lay clamped between the fingers of Ahmed’s left hand. The silence, in which we could hear Narayan Gopal’s song, lasted for a while which Ahmed probably interpreted as an indication for him to offer us, the two Nepali, a moment of privacy. He rose, planted his phone to his ear as if to call someone and said, “Bro, will be back in few minutes.”

Meanwhile Baje was staring at the floor of the stall. After that anticipatory stillness he stifled a sigh, the sigh of a heartbroken man, and began in an outburst of emotion, words pouring out of him in pure Nepali, “But my wife was not happy, son. Only in the beginning she was, but later, a year and a half later, she began to yearn for Nepal. She missed the hills, the rivers, the glitter of the Himalayas in monsoon. She was from mountains, and she pined for them, my poor woman. My little sparrow. She missed Nepal terribly, terribly so. I failed to understand, son. I failed to understand her. And how she suffered, my poor bird. I kept promising that we would return but never did.”

He paused and looked at the moonless night hanging ominously over New York. Sad but honeyed voice of Narayan Gopal was now singing another song. Baje closed his eyes, wiping the beads of sweat that had appeared on his forehead with the back of his palm. From his strained facial muscles, it was clear that he was reliving the memory associated with this song. Slowly his eyelids began to rise as he continued, “Doctors declared depression to be the cause of her death. But I know, I know, son. My woman died of yearning. My poor, poor sparrow. She couldn’t live away from Nepal, from her mountains and her rivers.”

Baje’s eyes were filled up with tears and the muscles of his jowls were twitching expectantly, as if waiting for someone to comfort him. Tiny, newly formed beads of sweat were again shimmering on his forehead. Not knowing what reply was expected of me I continued to look at him with the same grave, mournful expression. He hunched his shoulders as though attacked by a sudden cold wind and went on, “Son, life has been hard ever since my woman died. We two ran a restaurant in Queens on 29th Avenue. We were moderately successful. Yes, we were. Our son came and he worked with us for a while. Then my wife died. My sweet bird, she left me alone. After her death my son wanted me to sell our restaurant. And I did. What else could I do – a poor, widowed, lonely old man. And then he left too. How I have suffered! O god, what burdens I have to bear at this old age! I’m all alone now. But I don’t want to die like this, alone. Not in this foreign, distant soil. I miss Nepal. I miss the village I was born, the village where every tree and every pond and every bird knows me.”

“Baje, I’m really sorry for you,” I said in Nepali, feeling a lump in my throat. “Life has really been hard on you. But Baje, isn’t there any way you can return and live in Nepal now? Won’t that be better?”

“I don’t know, son. I don’t. We sold everything when we came here. Besides, my son doesn’t want me to go.”

“Don’t you have relatives there?”

“Relatives? We do, we do.” Baje looked anxious as though suddenly frightened of something. “But you can’t live at your relatives forever, son. After certain time you find yourself becoming burden on them. If I return home, say, tomorrow then I have enough well-wishers to sustain me there for at least a year. But after that, what! Besides, after certain time people would start asking questions: why you returned? Isn’t your son good to you? Did you do something wrong in America? All sorts of questions they will ask. I don’t think the gods want me to return home at all. I deserve this for letting my poor woman die.”

Baje’s small, wrinkled face seemed to become older and inaccessible as if the light, though faint and wavering, which had till then illuminated his heart with the only hope of returning home had also now been put out. As though by merely giving voice to his apprehension regarding his fate if he returned home, he had transformed it into an irrevocable reality. Wiping his tear-filled eyes he added, “It felt good to talk to you, son.” Only then did I realize that a brown couple was standing behind me, breathing impatiently as though in immense hurry. I paid for our two paan and as I took leave from Baje I could hear the guy speak in broken English, “Myself zarda paan. Sheself sweet, sweet paan.” The girl giggled voluptuously. I could tell, though I didn’t turn back to look, that the guy while saying, “Sheself sweet, sweet paan,” had tickled her chin with the tip of his fingers.

“Keep coming, coming,” Baje said, now in English, and waved at me as I walked across the crosswalk to the other side of the street. Ahmed was nowhere to be seen in that dismal corner of Jackson Height.

It was already dark now. The world seemed sadder and the great New York sky, despite its overwhelming burst of stars, gloomier. I found Ahmed talking on the phone a little way off. With one foot on the bench, he was leaning over its side arm and staring in my direction while at the same time mumbling into the phone. Under the influence of the pale streetlight his figure, though muscular and military-like, had an unmistakable air of dejected helplessness to it. When he saw me, he hung up and looked at me, then said in a lamentful voice of someone in tremendous distress, “Bro, that old man seemed so sad.” I didn’t say anything. Our steps echoed behind us as we walked in silence. Ahmed’s phone rang and, excusing himself, he began to speak into it. From the entreating softness of his voice I could tell he was talking to Noori. Besides, from my prior experience I understood that he must have flooded her inbox with messages and missed calls, so she had to call him. He was apologizing and trying to win her back. “I can’t live without you. No no, don’t hang up. Listen to me, listen,” he was saying. Whether it was the phantasmal glow of the lamps or the sight of Ahmed talking to Noori, deep within me as well a longing to call Kritika and at least hear her voice began to flutter its ancient, icy wings.

As I pulled my phone from the jeans pocket and looked for her number, the thought of the old Baje entered my soul like the glinting blade of a powerful dagger and, with it, the realization that never, never again will he be able to talk, or even hear the voice of the woman he had loved the most in his life. How petty and useless everything now seemed in light of this truth. Maybe today Ahmed would win Noori back, maybe today I too, after a long, tormenting discussion of course, manage to bring Kritika into my life again. But despite this, despite every effort one puts in to keep life in balance, the fact that there are forces, forces unimaginably powerful, forces beyond our reach, forces lurking right behind us and ready to extinguish the sunshine of our hard-won joys, that, that is terrifying. As we continued down the road towards our favorite Bengali restaurant, the voice of Baje, heavy as the moonless night itself, continued to reverberate all through me, “Meri Bechari Bhangeri: My poor sparrow. She couldn’t forget her mountains, her rivers.”