For us average laymen, a pretty good place to start might be by reading the book, “The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, What is the Question?” written by the guy who gave the Higgs Boson its nickname. Nobel Prize-winning physicist, Leon Lederman, with Dick Teresi, takes us through a journey from Democritus’ idea of the atom to the quest for the God Particle today. Published by Houghton Mifflin in 1993, the book is funny, witty, clear, and dumbed down to include minimal equations.[break]

Before we go any further, though, it should be understood that the book was written in the early 90s when plans for the Superconducting Super Collider or the Desertron in Waxahachie, Texas, was underway. The year that the book came out, 1993, was also the year when plans for the giant Large Hadron Collider in the United States collapsed. Physicists working on the Higgs Boson and other experiments that needed high energy collisions shifted their focus to the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). It was here that last month the announcement of the Higgs Boson was made.

From the media frenzy post-announcement, the things an average layman might have picked up are: the Higgs is super-super tiny; we don’t even know if it is the right Higgs; if it is the right Higgs, it supposedly gives mass to everything; and physicists claim that it is crucial to our understanding of the universe.

And back to that question: why is it called the God Particle?

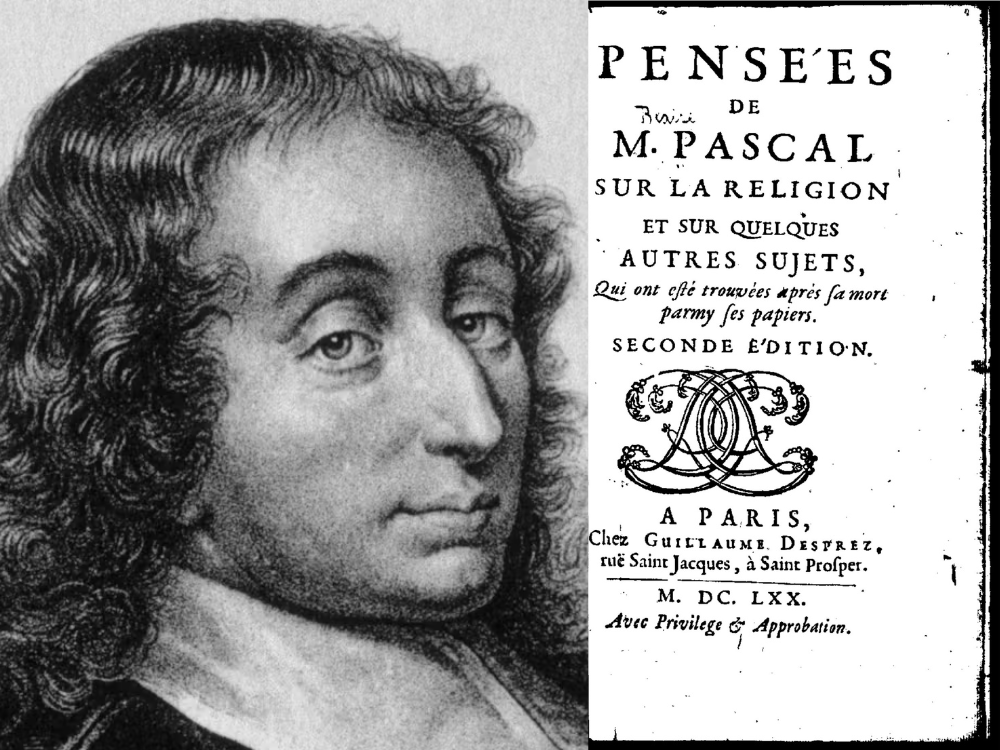

The name stuck after Lederman’s book came out. And Lederman explains why he called the particle so in the book: “Two reasons. One, the publisher wouldn’t let us call it the Goddamn Particle, though that might be a more appropriate title, given its villainous nature and the expense it is causing. And two, there is a connection, of sorts, to another book, a much older one…”

And then there starts the reinvention of the story of the Tower of Babel from the Bible under the ‘Tower and the Accelerator.’ It is not the first time that an attempt to rewrite parts of the Bible has been made, and Lederman, who is quite a humorist, keeps the reader interested through such storytelling techniques. Democritus’ part appears in dialogue form, there are plenty of allegories to explain ideas, many anecdotes, smattering of excerpts from literature, rhymes, and yes, the minimal, as Lederman claims, absolutely essential equations.

The book begins in a lighthearted tone with the beginning of the Universe. About what science tells us and the little we know. It transitions into the beginning of science and the story of Democritus, the Laughing Philosopher of Abdera, whose curiosity and imagination led him to simplify everything in the Universe to the idea of the atomus or the uncuttable. And quite unapologetically, the book then starts the story of Leon Lederman, and modern-day physics. The reader is accepting of this rather abrupt switch because of Lederman’s wit and humor. The gap is later bridged with the imagined dialogue with Democritus in Fermilab, Chicago, where Lederman was director.

Lederman is careful to contextualize and ground technical physics jargons before launching into ideas. However, toward the second half the book, by the nature of the subject, the book gathers jargons and grows heavy. Humor is abandoned here in favor of simplicity in the explanation of ideas, and anecdotes get sparse. The absolute necessity of equations grows higher and ideas get more and more mathematically abstract. Lederman even sneaks in an easy table or two. But it is easy to keep track, and for those literarily-inclined and fascinated by the sound of names, the jargons of physics borrow quite a number from literature, perhaps the most famous of which is Murray Gell-Mann’s christening of Quarks, after James Joyce’s “Finnegan’s Wake”:

Three quarks for Muster Mark!

Sure he not got much of a bark

And sure any he has it’s all beside the mark.

The span of the book is quite incredible, encompassing the works and lives of remarkable scientists and how it has contributed to our understanding of the Universe. How the quest for the God Particle began. And we meet the many explorers: Democritus, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Michael Faraday, Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac, Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, James Clerk Maxwell, Erwin Schrödinger, Abdus Salam, Melvin Schwartz, Jack Steinberger, Murray Gell-Mann, Peter Higgs, and many others. The book ends quite fittingly with the return of Democritus and an imagined dialogue on the future.

If science textbooks prescribed in our schools were as interesting, there would be a lot more interest in science.

Hamro Kitab: For the book-loving society