OR

Opinion

Shuvangi Khadka

Shuvangi Khadka is a researcher at the Samriddhi Foundation, an independent research and educational public policy institute based in Kathmandu.news@myrepublica.com

More from Author

In Nepal, a few banks and other private players are involved in the delivery of mobile financial services. However, all such independent practices are on a small scale as just an alternative delivery channel to the existing customers.

Nepal is gearing toward digitalization with the monetary policy of 2021/2022 terming FY 2021/2022 as “E-Payment Transactions Promotion Year”. On paper, Nepal is all set to give due emphasis to the development of necessary infrastructure and increasing awareness. It has also promised to make an arrangement for every person to receive social security allowance through the means of e-payments from the bank branches undertaking government transactions.

The goal is ambitious, however, with a large population of rural areas in Nepal still unbanked. Until August 2021, an estimated 67.3 percent of Nepalis have at least one bank account, with a huge gap in the number of accounts between males and females, and rural and urban areas.

To reach the unbanked population, the government has partnered with banks going beyond the brick and mortar structures through an approach popularly known as branchless banking. The most common forms of branchless banking include mobile banking, internet banking, electronic money, mobile money, and more. It is also the use of technology such as mobile phones and bank cards to conduct financial transactions electronically and remotely through third party outlets known as agents, allowing customers the flexibility to use financial services without going to bank branches. Nepal has frequently experimented with this mode, implementing projects like Human Development Social Protection Pilot (HDSPP) initiated in Kanchanpur and Dhadheldhura, Sakchyam's Branchless Banking Initiatives, and others initiated in Surkhet, Banke, Baglung, etc.

In HDSPP, Siddhartha Bank was chosen through a competitive bidding process which then trained 31 payment agents across the two districts. These agents were local retailers – vendors with enough cash flow who could transfer funds to beneficiaries using a point of sale device, which scanned their fingerprints and their cards, to verify their identity.

But these initiatives are being carried out on a small scale lacking huge investment and effort in transforming the digital dream into a reality- particularly for the unbanked distant population.

Nepal’s digital financial service landscape is just emerging, with 15 banks (until March 2017) cautiously venturing into this field and other non-bank Payment Service Providers (PSPs) gearing to venture and get licenses. With still a low percent of the banked population, there is a need to go beyond banking routes and diversify the delivery channels for welfare delivery to be more robust, rapid and efficient.

The success story of M-Pesa in Kenya illustrates the importance of innovative technologies in the easy delivery of welfare. Kenyan mobile network operator Safaricom introduced M-Pesa, where ‘M’ stands for mobile and ‘Pesa’ for money, as an initiative for financial inclusion dedicated to its under-banked population. It is a virtual banking system that provides services through a SIM card with no requirement of internet access and bank accounts. Like other mobile money systems, to make a deposit or get cash from the app, human agents are employed.

Later on, the service expanded to many other countries, and over time became a big player in the market for transferring or withdrawing money, saving or borrowing money, making merchant payments and paying bills. Mobile money payments have garnered considerable success over a decade, leapfrogging the formal bank structures. This signals how a country like ours with underwhelming infrastructures of banking can focus more on mobile money payment systems as a way to improve the lives of the unbanked.

However, replication of such a system requires a considerable amount of caution. For example, the first requirement for implementing such a system is to rectify the lacuna in data which merely tells the total number of subscribers but not the number of unique subscribers of mobile phones.

In 2021, Bangladesh decided to digitize its social assistance payments program called “Bhata” from transferring them into individual bank accounts to transferring the money on a mobile financial services (MFS) platform for newly enrolled beneficiaries.

Its effectiveness is yet to be judged but the transition itself was not very seamless. In some cases, the advantages were unevenly distributed while in some cases there were agents asking for an additional fee or a tip. Research in Bangladesh has also shown the need for collecting and analyzing data on how men and women experience technological changes differently as women are less likely to own phones.

In Nepal, a few banks and other private players are involved in the delivery of mobile financial services. However, all such independent practices are on a small scale as just an alternative delivery channel to the existing customers. While a few other implementations by private players are running in an unregulated way. All this, is said to indicate the existence of significant business potential for establishing large-scale mobile financial services platforms in Nepal.

Another way of doling out social assistance is through vouchers. In the digital world, there are electronic vouchers which are a type of cash-based response that allow beneficiaries of social assistance to receive relief for a variety of goods and services. Approved vendors who operate in the local markets where beneficiaries are located play a key role in this. A specific financial service provider is chosen who then generates the electronic vouchers in the form of digital money and handles the funds.

The e-voucher system has been used by different governments and INGOs like the World Food Programme (WFP) in different forms. The one used by the WFP enables it to even trace the entire value chain from disbursement to the expenditure of funds. Such back-end functionality helps in tracking the record of the utilization of funds in terms of the amount, balance, and stores where beneficiaries used the funds.

Recently, India launched its e-RUPI system that allows transfers of prepaid vouchers with specific purposes. All that a person would need is a mobile number. An e-RUPI voucher can be sent either as an SMS (for non-smartphone users) or as a QR Code (for smartphone users). The voucher can then be redeemed without a card, digital payments app or internet banking access, at the merchants accepting them.

The practice of digitizing social security allowance payments from around the world nudges toward rethinking of public-private partnership- particularly redefining the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder, as evident when comparing the procedures in the traditional and alternative system of payment. The preliminary activities related to identification and enrollment of beneficiaries still remain within the purview of DDCs or VDCs but the private sector handles the disbursement part of the process.

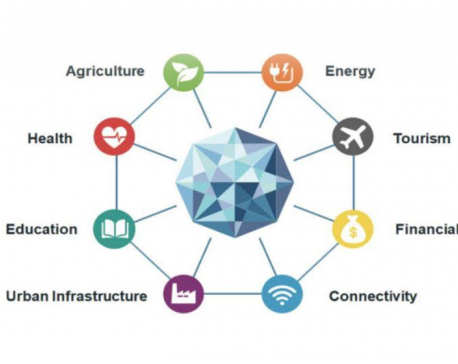

Banks, institutions providing microcredit to other financial services such as post offices and money-transfer companies, telecom companies, etc. can collaborate as implementing partners. Many programmes using e-payment systems have been based on partnerships with private sector service providers that have developed or own the technologies.

While we experiment with new technologies, the existing distribution channels of agents can be better utilized. Such agents should be trained and employed to not only disburse funds but also to spread financial information and literacy among the wider population. Enhancing digital literacy must not only focus on teaching beneficiaries how to use digital tools but also educating them on the safe and secure use of digital instruments.

Despite the business potential, the private sector may be reluctant to back up such an initiative by employing a number of agents as it might prove costly before turning profitable -- particularly in Nepal with considerable geographical challenges and uneven population distribution. In such a case, only a system rolled out on a large scale can withstand its costs. For this, the public-private partnership needs to be better strengthened. And for this, the government needs to create a favorable environment and an enabling policy for correlation and collaboration between stakeholders of the MFS ecosystem.

You May Like This

Efforts at digitizing government services in current federal set-up

Information and communications technology (ICT) has been taken as a key driving force in transforming the traditional Nepali society into... Read More...

Just In

- 19 hydropower projects to be showcased at investment summit

- Global oil and gold prices surge as Israel retaliates against Iran

- Sajha Yatayat cancels CEO appointment process for lack of candidates

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

Leave A Comment