OR

Attracting foreign investors to Nepal will require a mapping out of competitive edge over other countries that compete with Nepal for the foreign money

Government of Nepal has started soliciting investment money from foreign groups by inviting potential investors—foreign as well as domestic—to periodic Investment Summits. The first such summit took place in March 2017 and the second one is planned next month in March.

The experience from the first Summit has been disappointing but the response was not that disappointing—some $14.5 billion was pledged by 40 investors coming from 26 countries. But the latest assessment of the Summit results show less than $1 billion worth of investment under serious consideration of which may be just a fraction will likely be realized.

In the absence of hope for results from Investment Summit, many interested groups find it puzzling that government has come up with the idea of a Second Summit. One better option would have been for the government to carry out a close evaluation of the first Summit outcomes to help organize for a second Summit. Such a follow-up would then convince the investors that Government is truly interested in getting the pledged projects started and also know of the roadblocks that were causing the delay.

There is little evidence, however, that Government has actually done any such preparatory work prior to coming up with the idea for a second Summit. It wasn’t surprising then that US Embassy in Kathmandu has advised the Government not to go ahead with the Summit without first conducting a review of policy weaknesses and operational difficulties investors face for making good of their pledges, most of it catalogued in the 2018 World Bank Report on Doing Business.

Falling behind

Doing Business Report ranks Nepal at 110 among a total of 190 countries chosen for the rating index. Among the neighboring countries, China, India, Bhutan have got noticeably better rankings than Nepal while Bangladesh is ranked lower at 176, one of the worst rankings in Asia.

Unlike foreign grants and loans which have dominated Nepal’s foreign capital account—almost all of which have come from bilateral and multilateral sources—they reflect, in large part, political decisions rather than commercial profitability of the targeted investments that usually is the case with regard to foreign direct investment (FDI). The small-size receipt of FDI by Nepal—just one to two billion dollars over the past one decade—can then be sourced to the outlook of low level of business profitability in Nepal and not the lack of goodwill or unwillingness of doing business. It then follows that attracting foreign investors to Nepal would require a mapping out of competitive edge over other countries that compete with Nepal for the foreign money.

World Bank annual report on Doing Business offers an excellent guide as what a country is needed to do to get a better ranking on the index that, most likely, all potential investors consult before committing their money to a particular country. Doing Business document provides an exhaustive profile of business conditions in all of the surveyed countries (190 countries altogether). Countries that are eager to attract foreign investment would need to work on reforms to improve ranking on Business Environment Index, which gets more attention than any other improvements for a host country to attract foreign investors.

Reflecting that Nepal does have a business environment problem, of the pledged FDI of about $450 million during the first 10 months of fiscal 2018, 87 percent is from Chinese investors. The next largest group of investors is from India, at seven percent, and the rest six percent are mainly from the United States and Korea. While the size of committed investment isn’t necessarily low, the pledged investment can’t be said to be an ideal distribution of sources, for the reason that most investment from China is in infrastructure that isn’t necessarily driven by a profit motive as generally is the case with FDI.

If Nepal offers better incentives for doing business in the country, investors from neighboring countries will exploit such opportunities more readily than investors from the distant countries.

Areas to improve

There are many areas the government needs to look into for improving business conditions. Doing Business lists eleven of such conditions but one immediate reform that is urgently needed is related to taxes levied on business enterprises, foreign as well as domestic. At this time, investors not only pay a 25 percent company tax with very few deductions, they also pay 13 percent value-added tax and 10 percent social security tax. With this level of taxation, very few businesses will be willing to establish shops in Nepal if much lower or no tax regimes prevail in other competing countries.

One larger question relates to the investment itself. Why do countries seek higher levels of investment, from domestic as well as foreign sources? The simple and explicit answer is that investment is a key input in the production process. Directly, businesses need capital to build factories and purchase equipment and also indirectly the government builds roads, establishes electric grid, builds irrigation canals, provides education and health facilities and many such other things. The point is that even if other production inputs like land and labor are available in plentiful supplies, no production processes can start without capital. Investment is needed for starting the production process and larger amount of investment money facilitates higher production.

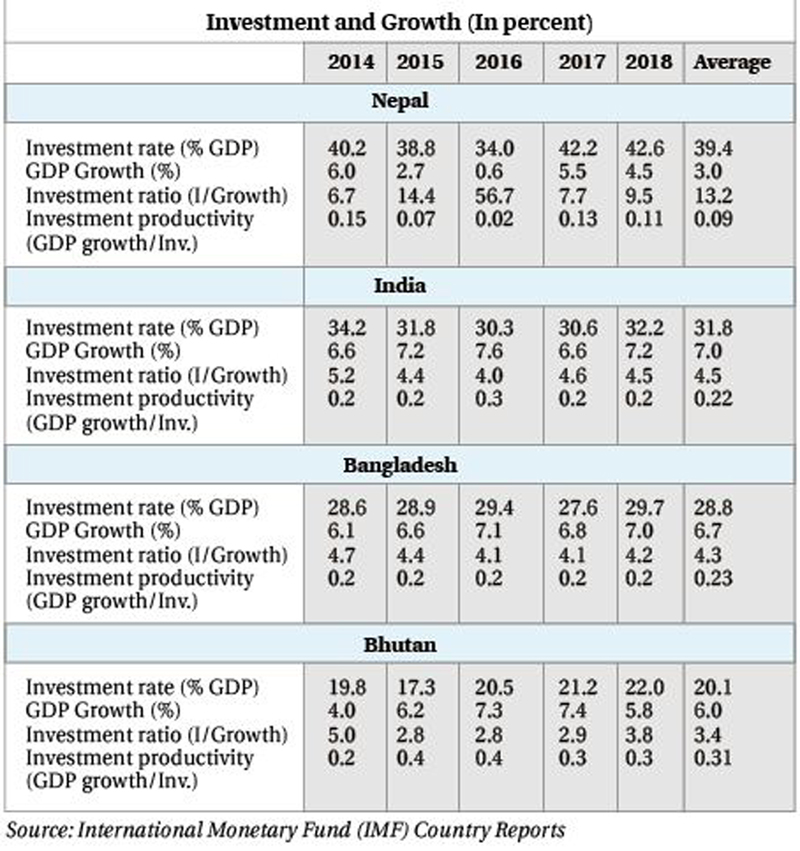

However, production and investment data presented here (see the table) for Nepal suggest no such relationship. Looking at Nepal by itself and also relative to other regional countries, at almost 40 percent investment rate— highest level among regional countries—Nepal registers the lowest growth at three percent on average per annum over a five-year period. This is just half or a lower growth rate in comparison to the regional countries. Another way to look at these figures is to compare them in terms of investment productivity—growth in output per unit of invested capital, which, at a 0.09 ratio for Nepal, is less than half in other countries and, less than one third of Bhutan’s.

The data then suggest a disturbing discovery with regard to capital use in Nepal. That much of the investment the country makes produces little or nothing in terms of output value. As the data above show, with just half of investment rate for Bhutan, the country produces double the amount of output, compared to Nepal. It appears that much of the investment resources in Nepal gets inefficiently utilized or outright wasted.

The challenge for Nepal then is not that it gets a larger amount of investment capital for producing larger-size growth but that it needs to invest wisely of whatever it claims it invests which also looks doubtful. The problem lies, more likely, in its national accounting practices that are archaic and handled by untrained staff.

The author teaches economics at NOVA College, Virginia

sshah1983@hotmail.com

You May Like This

Complete education, full health could double Nepal's GDP per capita: WB

KATHMANDU, June 7: Nepal has the potential to double its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in the long run if... Read More...

Jan 7: 6 things to know by 6 PM today

Your daily dose of missed important news of the day. ... Read More...

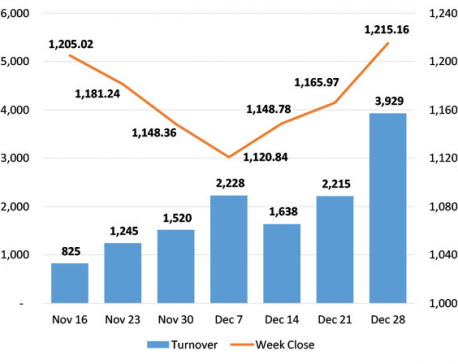

Stocks extend rally for third straight week

KATHMANDU: Trading began on a highly positive note this week as the Nepal Stock Exchange (Nepse) index shot up more... Read More...

Just In

- Qatar Emir meets PM Dahal, bilateral agreement and MoUs signed between Nepal and Qatar

- Employee involved in distribution of fake license transferred to CIAA!

- Youth found dead in a hotel in Janakpur

- CM Kandel to expand cabinet in Karnali province, Pariyar from Maoist Center to become minister without portfolio

- Storm likely to occur in Terai, weather to remain clear in remaining regions

- Prez Paudel solicits Qatar’s investment in Nepal’s water resources, agriculture and tourism sectors

- Fire destroys 700 hectares forest area in Myagdi

- Three youths awarded 'Creators Champions'

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment