OR

Failure to secure justice through the transitional peace process provides the moral justification that sustains corruption in Nepal

It wasn’t exactly the New Year’s greeting that the government was expecting.

Two days before New Year, on April 12, 2019, the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Commission sent the Government of Nepal a letter expressing concern about the lack of progress in the transitional peace process.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP) make up the transitional peace process in Nepal. It is a core part of the peace agreement between the Maoist and the government that ended the conflict.

The UN Human Rights Commission was concerned about the “protracted transitional justice processes and delays in establishing the measures that should guarantee the right to truth, the delivery of justice and access to repatriations to the victims.”

Nepal’s decade long conflict inflicted a huge cost: 17,866 lives lost, 1,530 disappeared, 8,191 maimed, millions displaced.

Government’s initial response to the letter was brief and terse.

“Nepal is capable of handling the transitional justice process on its own,” Minister for Communication and Information Technology Gokul Banskota said in his weekly press briefing.

The continued delay and obstruction in the transitional peace process has been equally expensive: it is a setback to “meaningful reconciliation through transitional justice in Nepal and damaged the hopes of victims to obtain justice for the violations suffered,” UN’s letter noted.

The lingering psychological trauma of war and the damage of hope are not the only impacts of the failure to secure justice, establish truth and reconciliation. Even for people outside the direct impacts of war, it continues to shape our judgement and morality. It explains why many of our challenges, deep-rooted corruption for example, continue to persist.

Endemic corruption

Corruption has become pervasive across all segments of society. From small to big tasks, private sector to public institutions, mundane everyday activities (like buying movie tickets) to deeply spiritual one (like offering a prayer in a temple), corruption has become institutionalized and acceptable.

Our response to corruption is very institutional. We have more laws, more stringent requirements, more powerful watchdogs, more oversight agencies, more resources to investigate and prosecute. But these efforts are collectively failing. Despite an elected central government with a clear majority, despite three levels of elected governments, despite empowered citizens, despite a free press, our efforts to prevent and curb corruption are failing to yield any meaningful results.

In the previous regime, a monarchy with absolute centralized authority, high levels of corruption were understandable. But why is it that even with a reasonably democratic system, with all the legal, financial and institutional resources at our disposal, corruption remains as entrenched, as pervasive, if not deeper than it was before?

How did we get here?

One common answer to this question is to blame the greed of political leadership. But beyond the surface of this argument, it is hard to justify how the individual greed of politicians alone perpetuates this level of corruption.

Another common response is to blame the system. Like a giant whirlpool, corruption pulls everyone in—from the peon to the minister and interest groups outside. But beyond the surface of this argument too, it is hard to justify how this large eco-system thrives purely on its interdependence.

Personal greed or the eco-system cannot be the explanations for why corruption is so entrenched in Nepal. Those factors are merely the symptoms. The causes of corruption lie elsewhere. In our morality and our social consciousness of what is right and wrong.

Today, corruption is pervasive in Nepal because it is morally acceptable. It coexists with our fear of God and our consciousness of what is right and wrong. Nepal’s history—particularly the beleaguered transitional peace process that is failing to deliver justice—is continually providing us the individual moral basis and personal justification for being corrupt.

Who is your hero?

Every generation requires a hero, someone that personifies their aspirations and hopes.

Pushpa Kamal Dahal “Prachanda” is this generation’s hero. Rising from a humble background, he built a movement on the promise of change. He commandeered his forces to achieve stunning and radical political change. Along the way, he has become Prime Minister, reunited with his old communist comrades and emerged as one of the most powerful personalities not just in Nepal but across much of Asia.

As much as Prachanda’s story is about perseverance, sacrifice and conviction, it is also a story about the need for power, wealth and influence. Prachanda’s story is an inspiration for how the end justifies the means.

Prachanda justified conflict, brutality and violence of the insurgency as necessary means for the political and social change that it brought.

Today, Prachanda lives in a big house, drives a big car and (supposedly) has a tremendous amount of wealth. He has delivered on his promise for political change. Perhaps the most stunning turnaround came earlier this year. After decades of labelling Prachanda a terrorist, the United States hosted him and his family in their country, allowing them to benefit from the most advanced medical care of the US.

Who wouldn’t want to be like Prachanda? For this generation of Nepalis, there could be no bigger hero than Prachanda.

Just as Prachanda used the end to justify the means, we all justify our engagement on corruption. We accept and engage in corruption, because we have convinced ourselves that in the end, we will be good, we will be generous, God fearing, help those in need and leave a lasting positive legacy.

This corruption, we tell ourselves, is only a short-term interim measure, an absolute necessity, to get to where we need to get to do better things in the future.

In the conviction that we will do good in the end, we justify the means we pursue. If the United States could forgive a person they previously termed as terrorist, surely God will also forgive us for a bit of thievery and corruption along the way.

When the end justifies the means, corruption is never wrong. We calibrate our moral compass to account for this. Having thus justified to ourselves the moral rationale for corruption, we then tell our friends, our colleagues, our children about it and before you know it, corruption is endemic. We accept it without the slightest remorse.

Legal and institutional responses can solve functional corruption. It cannot end corruption when it is morally acceptable.

Reclaiming moral compass

This is where our transitional peace process must take on additional meaning and purpose.

The importance of our transitional peace process isn’t just about securing justice, repatriations and reconciliation. A much deeper moral truth is at stake.

In our search for peace, we must find a way to establish that the end doesn’t always justify the means, in much the same way corruption today cannot justify the promise for a better deed tomorrow. To reclaim our moral compass, we need history to show us the way.

The transitional peace process must secure justice and repatriation to establish that the ends do not always justify the means—there is a line between good and bad, right and wrong. The truth and reconciliation must help us recalibrate our moral compass.

A country may have a flag and anthem, but without a good moral compass it won’t be worth fighting for.

Bishal_thapa@hotmail.com

You May Like This

Media for democracy

In a modern democracy, citizens feel empowered when they have adequate access to truthful information without which they cannot take... Read More...

The Modi ripples

When two elephants make love, the Tibetans get squeezed out from India and, it will not be a matter of... Read More...

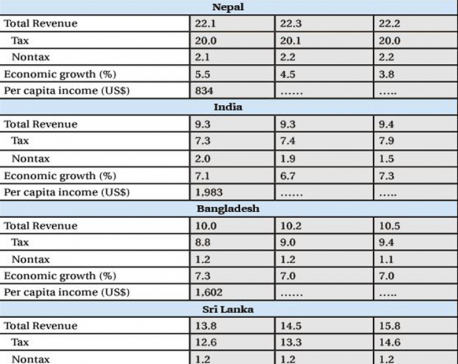

Tax exploitation in Nepal

High taxation policy pursued by Nepal has worked as a powerful drag on the economy by hurting private sector incentive... Read More...

Just In

- Govt receives 1,658 proposals for startup loans; Minimum of 50 points required for eligibility

- Unified Socialist leader Sodari appointed Sudurpaschim CM

- One Nepali dies in UAE flood

- Madhesh Province CM Yadav expands cabinet

- 12-hour OPD service at Damauli Hospital from Thursday

- Lawmaker Dr Sharma provides Rs 2 million to children's hospital

- BFIs' lending to private sector increases by only 4.3 percent to Rs 5.087 trillion in first eight months of current FY

- NEPSE nosedives 19.56 points; daily turnover falls to Rs 2.09 billion

Leave A Comment