OR

Way ahead for LDCs

Published On: December 7, 2017 01:00 AM NPT By: Gauri Pradhan and Sudhir Shrestha

Gauri Pradhan and Sudhir Shrestha

Pradhan is Global Coordinator of LDC Watch and Shrestha an intern at the same organizationnews@myrepublica.com

More from Author

LDCs seek reforms in agriculture through the end of domestic support or subsidies and a special safeguard mechanism.

Thirty-six of the 47 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in the world are members of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Seven others are in negotiation for accession to the global trading regime. WTO negotiations hold much significance to the LDCs, including Nepal, as the 11th session of WTO Ministerial Conference (MC11) is being held in Buenos Aires from December 10 to 13.

The Doha Development Round, which was launched in 2001 with the objective of improving trading prospects of developing countries, particularly LDCs, was a turning point in the WTO’s history. It paved the way for further discussions on making trade fair to the developing world. But though the Doha Round has reached its 16th year of negotiation, it has not brought about mandated reforms in global trade in favor of LDCs and its successful conclusion seems doubtful even today. Likewise, the Bali Package (2013) which includes provisions for lowering import tariffs and agriculture subsidies to help developing countries in their trade with developed countries is not fully operational. In this context, MC11 is significant for LDCs.

Divided house

The 10th Ministerial Conference held in Nairobi in 2015 was a divided house. In the Nairobi Declaration, some countries kept themselves away from reaffirming their commitment to the Doha Development Agenda. Their underlying argument was that the Doha Round was already taking too long and economic power play and priorities had changed with time. But this also raised doubts over whether the WTO would be less responsive to the needs of the developing world. This indicates that the WTO is drifting away from its consensus decision-making and is increasingly becoming a ground for North-South battle. The deep division is also seen in the negotiation in the run-up to MC11, as the US has already clarified that it will not be part of any decision at MC11.

LDCs seek reforms in agriculture through the end of domestic support or subsidies, introduction of Special Safeguard Mechanism (SSM) and a permanent solution to public stockholding. Large domestic subsidies, mainly in the US and the EU, artificially depressed price of agricultural exports on which many LDC economies depend. In addition, these harmful subsidies have, among other things, caused overfishing, decimating in the Small Island Developing States (SIDs). To protect domestic agriculture from such artificial fall in commodity price due to unfair subsidies or import surges, LDCs have been demanding Special Safeguard Mechanism, which will give them the flexibility to temporarily increase tariffs in such cases.

There has been limited success in terms of Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT) provisions that exempt LDCs from the same strict trade rules and disciplines as those of more industrialized countries. Non-tariff measures, such as Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and Technical Barriers to Trade, restrict LDCs from increasing market access of their products. Meanwhile, LDCs have not yet received any significant technical or financial support under Article 66.2 of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which had assured LDCs of proper technology transfer to create a sound and viable technological base.

However, in the MC11, instead of focusing on finding a logical conclusion to the unfinished business of the Doha Round (as outlined above), developed countries and some developing countries are moving towards new issues such as e-commerce regulation, integration of micro small-sized medium enterprises (MSMEs) into global trade mechanism and investment facilitation.

Safeguarding our rights

The LDCs should press for successful completion of the Doha Round and get LDC-specific issues addressed before they move to newer agenda. LDC governments should stand against giant global data companies, along with the European Union, amending e-commerce rules to replace the discussion option with legally binding entry in the MC11. LDC governments should formulate domestic protection policy for MSMEs before introducing e-commerce. In addition, a group of countries has submitted a proposal that calls for MC11 to agree on greater transparency and access to information related to government regulations on food and product safety so as to facilitate the participation of MSMEs in global trade. LDCs should unite against such proposals as they may increase administrative burden on LDCs and also impinge on a country’s right to regulate.

MC11 needs to be linked with Bali outcome and Doha Development Package. LDCs must push for rapid implementation of commitments made during past Ministerial Conferences such as rectification of trade-distorting measures in agriculture; elimination of unjustified non-tariff barriers; timely implementation of DFQF market access on a lasting basis; simple, transparent and predictable preferential rules of origin; implementation of S&DT provisions; operationalization of service waiver; an increase in assistance through Aid for Trade (AfT) mechanism. In this context, LDC Watch’s demand, put forth in Mid Term Review of Istanbul Programme of Action in 2016, for free and fair trade within the regime of World Trade Organization (WTO) and beyond in terms of bilateral, regional and plurilateral trade and investment agreements are still relevant.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Istanbul Programme of Action for LDCs for the Decade 2011-2020 (IPoA) both call for doubling the share of LDCs in global exports by 2020, including by broadening LDCs’ export base. To improve their miniscule export performance which currently stands at 0.97 percent of world export, LDCs should present a united front and negotiate for successful and speedy conclusion of the Doha Round. Given the limited technical staffs and negotiating skills, LDCs also need to build their negotiation capacity in new issues of e-commerce and investment facilitation. The LDC Consultative Group, currently led by Cambodia, must play an active role in forging strong cooperation and engagement for the negotiation.

LDCs like Nepal, which is in the process of graduation, should form mid-term strategies realizing that after the end of the three-year transition period on graduation, they are going to lose special support measures associated with LDC status. Graduation is important for LDCs like Nepal. It is a milestone for attaining sustainable development in the long run. Therefore, aid for trade approach needs to be continued in order to support the LDCs that have graduated for certain time.

Pradhan is Global Coordinator of LDC Watch and Shrestha an intern at the same organization

You May Like This

Province 3 way ahead in economic, social indicators: Report

KATHMANDU, June 15: Province 3 has the highest per capita income with people here earning an average US$ 1,534 annually while... Read More...

Right way to begin, yet a long way to go

“A woman is like a tea bag, you never know how strong she is until you put her in hot... Read More...

CIA officer reveals the bizarre way dictator Saddam Hussein spent his last days in power

Former CIA Senior Analyst John Nixon's new book "Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein” provides never-before-seen details into... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

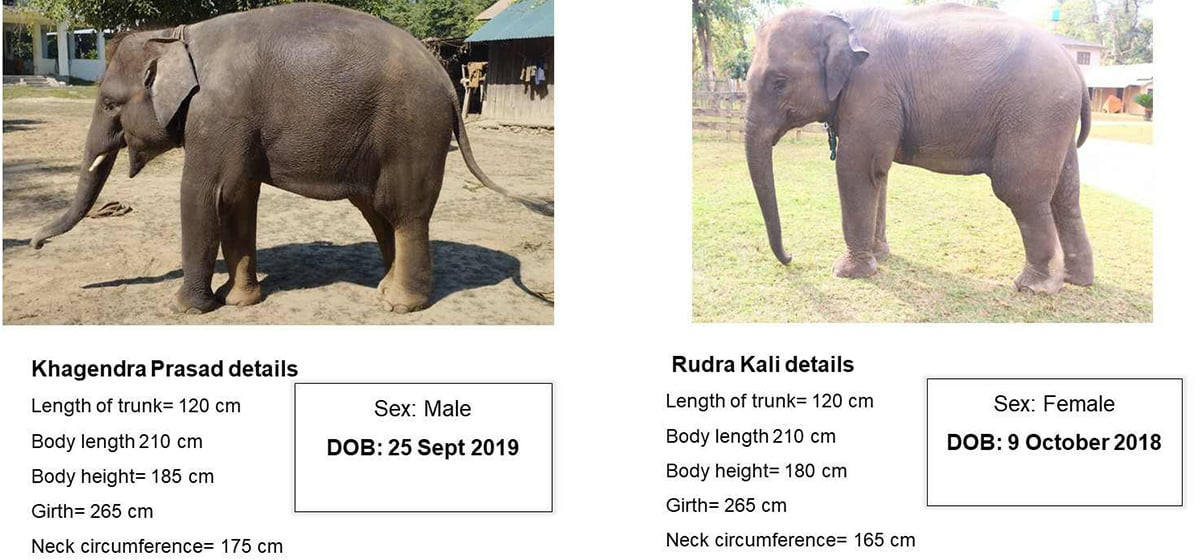

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to initiate release of Bipin Joshi

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

- Devi Khadka: The champion of sexual violence victims

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment