OR

Transitional Justice in Nepal: Justice Delayed, Collective Conscience Denied

Published On: June 12, 2021 12:18 PM NPT By: Apurva Singh

The aphorism “justice delayed is justice denied” could not be more hurtful and real for the victims of the armed conflict.

It has been over seven years since the enactment of the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act, 2071 (2014), and more than 16 years since the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord, and yet the victims of the Maoist insurgency and their families await justice. The preamble to the Act states that it was enacted inter alia with the aim “to provide relief to the families of the victims who were subjected to disappearance during the course of the armed conflict” and “to constitute a high level truth and reconciliation commission to investigate the facts about those involved in gross violations of human rights and crimes against humanity during the course of the armed conflict, and to create an environment of reconciliation in society”. Needless to state, this aim is nowhere close to being met, and in this column I examine why.

The Act establishes two commissions: a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons. These bodies are entrusted with the responsibility of investigating matters relating to incidents of gross violations of human rights, and enforced disappearances respectively. While the Act, on the face of it, seems functional enough as a step toward the right direction, its structure, language and vision make it deeply problematic for many reasons. For instance, Section 26(2) and Section 26(4) of the Act allows for granting amnesty to perpetrators based on very flimsy grounds, namely, acceptance of commission of gross violation of human rights in the course of the armed conflict, acceptance of regret of committing such an act, apologising to the victim to their satisfaction before the Commission, and a promise that they would not repeat any such act in the future. It is rather alarming to note that the government in its wisdom believed that such patronising language and acts, and miniscule form of reparations could possibly countenance gross human rights abuses. Further, it is evident that apologies, promises, and a façade of a show of those could be easily orchestrated and manoeuvred by powerful perpetrators by subjugating victims and their families into acceptance.

This provision was rightfully struck down by the Supreme Court of Nepal in Suman Adhikari et al v. the Office of Prime Minister and Council of Ministers in 2015. However, it was subsequently challenged by the government in a petition and was struck down again by the Supreme Court in 2020. This shows that the government has been repeatedly pushing to retain the unreasonably lenient amnesty provisions so as to be able to use it to their advantage. While the provision remains rightfully repealed, it is naïve to assume that it has been laid to rest fully as it is still nascent to predict what the government plans on doing next about this issue.

Another major alarming feature of the Act is that it is silent on any form of timelines. The lack of timelines for investigation, prosecution, incarceration, action and many more shows that the Act was not designed to accommodate the concerns of the victims and their families. Further, the fact that the two commissions set up under the Act have failed to prosecute, let alone incarcerate, a single person despite there being over 17,000 casualties, shows that the commission was formed largely to appease foreign onlookers and perpetrators responsible for the acts. The optics of the commissions was designed to ensure that while the perpetrators would remain exonerated from any wrongdoing, even those with an eagle-eye view of the nation would be under the fictitious impression that the government is indeed taking action as there does exist a transitional justice law, even if the law itself has failed to produce results. The pain suffered by the victims and families resonate louder than the lies regurgitated by the responsible bodies. The collective conscience of our nation is still haunted by the atrocities of the civil war and as a nation, Nepal cannot possibly move forward without providing reparations to the victims and families. The civil war forms an intrinsic and inseparable part of the Nepali history, which has been overlooked for far too long. Any denial and delay of compensation is equivalent to denial of that history and thereby the pain suffered by the victims and their families. Nepal’s national collective conscience rests on the notion that the commissions would bring all perpetrators of the crime to justice. But the reality is that the Act, the commissions and the promises thereunder are soon to become paper tigers.

The aphorism “justice delayed is justice denied” could not be more hurtful and real for the victims of the armed conflict. As the country waits in anguish for any action on part of the commissions to prosecute and incarcerate perpetrators of the civil war, the painful reality might just be that the victims will never be able to get justice. One suggestion could be to amend the Act to ensure that there are flexible, if not stringent, workable timelines for the two commissions within which they must act on the provisions of the Act. Further, the Supreme Court should exercise its exemplary jurisdictional powers to enforce the provisions of the Act in letter and spirit and treat such unreasonable delays as a violation of the Act, while also setting in stone that no amnesty shall be granted.

(The author is a legal associate at a law firm)

You May Like This

Nine ruling parties pledge to conclude transitional justice issues without further delay

KATHMANDU, March 6: Nine political parties represented in the House of Representatives (HoR) have pledged to complete the rest of the... Read More...

Stakeholders prepare for consultations on TJ bill

KATHMANDU, Nov 20: The government is preparing to hold consultations on the draft of the Transitional Justice (TJ) bill in... Read More...

TRC expresses concerns on data security

KATHMANDU, April 12: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has expressed concerns on data security. The TRC and Commission of Investigation... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalgunj ICP handed over to Nepal, to come into operation from May 8

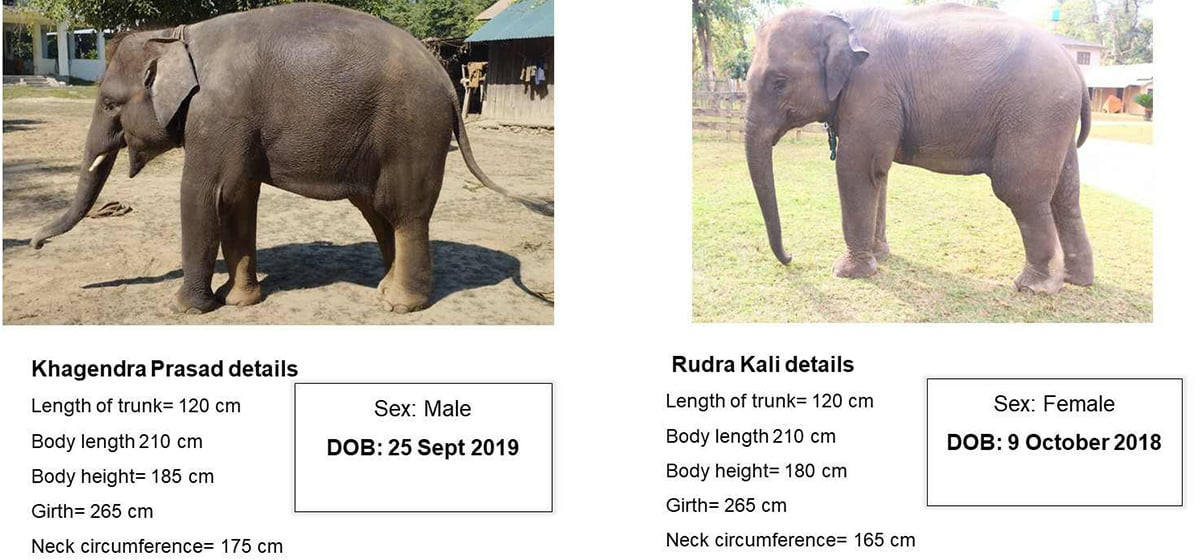

- Nepal to gift two elephants to Qatar during Emir's state visit

- NUP Chair Shrestha: Resham Chaudhary, convicted in Tikapur murder case, ineligible for party membership

- Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha: A visionary leader transforming healthcare in Nepal

- Let us present practical projects, not 'wish list': PM Dahal

- President Paudel requests Emir of Qatar to help secure release of Bipin Joshi held hostage by Hamas

- Emir of Qatar and President Paudel hold discussions at Sheetal Niwas

- Devi Khadka: The champion of sexual violence victims

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment