OR

Book Review

Shradha Ghale’s Kathmandu Leela: Setting new challenges and standards in novel-writing

Published On: December 21, 2018 09:42 AM NPT

At the very outset, and seemingly offhand, I extract the very first paragraph from Mr. Louis Menand’s latest essay in The New Yorker, of December 10, 2018, which opens in this way:

If a book is good, if it’s artful, entertaining, and informative, should it matter who the author is? Once upon a time, many readers would have said no. It was a longstanding protocol of book appreciation to consider things like gender, sexuality, ethnicity, personal vices, personal virtues (if any), and prior reputation of the author irrelevant to a book’s merits. You could disapprove of a writer’s politics and prejudices if they showed up in the text; otherwise, they were customarily bracketed off. [My emphasis]

Mr Menand’s topic is “Literary Hoaxes and the Ethics of Authorship” and therefore quite out of the context of this review. But the above excerpt applies to the novel and its author under review wherever it is apt and to the mark. By saying so, it also touches all of us who are tagged as ‘Nepali Writers Writing in English’ – NWWiE. These stands will stand out in the following paragraphs.

There are merely a dozen creative writers in the Nepali world of letters at large at present: Two or three Newars, one Chhetri Thapa, some five Bahuns, one Thakuri Singh/Shah, one Limbu, one Gurung, one Lepcha, one Karki, some Madheshis – and now, one Ghale. I include writers of all genres: Long and short fiction, poems, lyrics, plays, criticism, and other literature forms.

They are of different faiths, too: Hindus, atheists, animists, Buddhists, Lamaists, agnostics, Protestant, and the like. The Chhetri, Bahun and Thakuri writers are of high Hindu castes and come with their historical and cultural baggage of feudal and gentrified lines and leanings. They also went to the best of schools and MFA citadels in the West. The Newars are of mixed heritage – mercantilists, bureaucrats, Hindus, Buddhists, and such much. The Limbu and Lepcha authors are Kirantis of the east while the Gurung and Ghale writers belong to west Nepal’s ethnic nationalities. The single Singh/Shah writer hails from southwest Nepal. I also must mention those Rana creative writers, by birth and marriage.

The Nepali cosmos, therefore, is not as homogenous as, say, Korea or Japan, and the social and economic backgrounds of the writers are also varied: Some of us subaltern writers have been to dusty and vernacular mofussil schools in the Himalayan hills while the privileged ones of the cities have been educated in the best institutions of the world. Roughly speaking, the writers in Nepal have Kathmandu as their hometown or homing destination, and our creative brethren outside hail from Gangtok and are dispersed in Indian cities and abroad.

Shradha Ghale is an exception to me. Born of a western Ghale and an eastern Bantawa Rai parents, her original clan place happens to be Bhojpur which is focally between the west and the Kirant. Another exception is Shradha’s translocation in Kathmandu, it being her birthplace and everything after that. More of it will follow in the following lines.

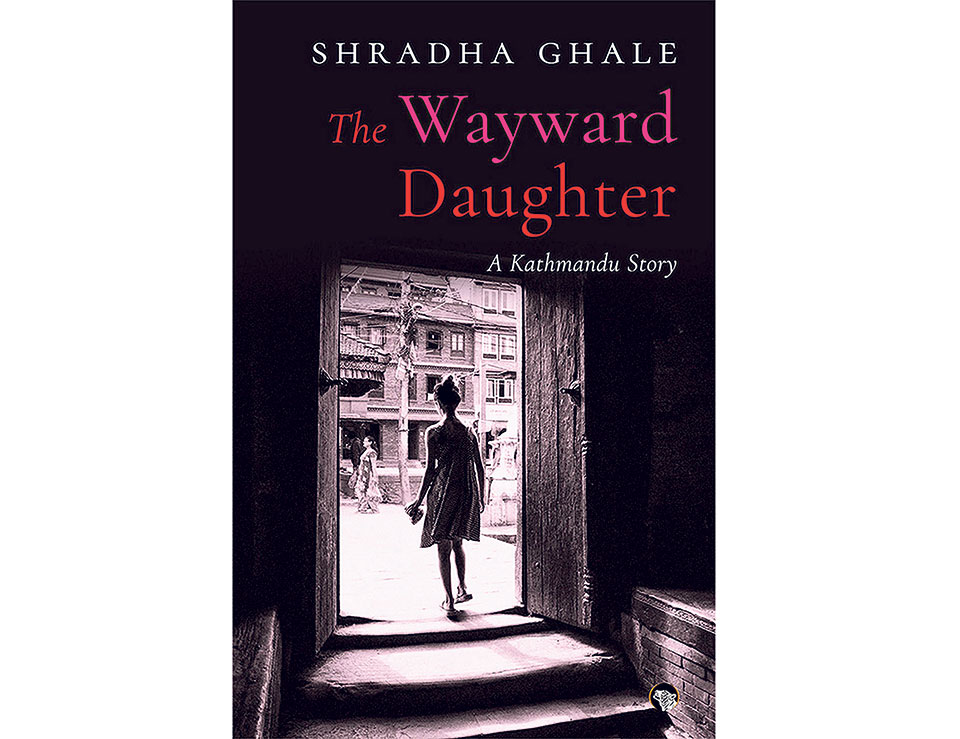

As soon as I finished reading “The Wayward Girl: A Kathmandu Story” by Shradha Ghale, I realized that the old school of novel-writing by the NWWiE in Nepal and outside are over and done with. Here is a work of fiction that is originally different from the previous narratives written, as if with constipated grunts, in forced and foreign forms with mainly ‘development’ and ‘advocacy’ contents. That this new thunderbolt is hurled by an under-40 female writer in her debut novel is a proper death sentence on the privileged jury of Nepalis writing in English hitherto: That Nepali writers must reinvent and remodel themselves in their next body of works, and that their days of “interesting” writing are now over.

Coming to Shradha Ghale, we have the best admixture in this youngest novelist among us; being a female is another added bonus. As said before, her father is a Ghale, an Adibasi Janajati Nation of west Nepal – along with the Gurung and Magar Indigenous Nationalities – while her mother is a Bantawa of the Rai Nation in the Kirant Confederation. This combination gives Shradha the identity of a double indigenous nationality in Nepal. Both her parents’ forbears seem to have migrated to Bhojpur in mid-Kirant, and now the Ghales make Kathmandu their permanent home.

Our youngest novelist also had the best of education: Born and growing up in Kathmandu, she was schooled at the most meritorious St. Mary’s; she had her BA in literature and anthropology from Bennington College in Vermont, the US; and she obtained her MA degree in English Literature from the University of Westminster, London, the UK. So this dual indigenous Nepali is amply qualified as well. She has the best of the Nepali world: heritage and learning.

With these preambles, it is now time to review the pages of The Wayward Daughter.

The Wayward Girl is written in a simple flow, with no literary pretenses. The storyline is clear in 50+2 short and curt but articulate and illuminating chapters which are peopled by polite and humble characters whose origins are in the Himalayan hills of hard and difficult Lungla in Bhojpur – a locale that is also pitiably mentioned in the writing of Lil Bahadur Chhetri of Guwahati, and Indra Bahadur Rai of Darjeeling – and are fated to be in Bhaisichaur of cruel and pitiless Kathmandu. Mr. CK Lal’s notion of a novel with characters 1) arriving, 2) settling down, and 3) leaving is to the point in this short but crisply loaded novel. The conflicting collocations between Lungla and Bhaisichaur are stark and shocking.

The Tamules – Gajendra ‘Gajey’ Bahadur Tamule of Lungla in Bhojpur, his wife Premkala Limbu, and their two daughters – are between two worlds which are mutually dichotomous. If “Lungla was a hard and inhospitable land, a place of lack and adversity, just another ‘remote village’ in the hinterland,” (p. 27) in the eyes of Sumnima and Numa, the Tamules’ city-bred daughters, what of Kathmandu itself? Tamuleji feels that “The city diminished his kinfolk, reduced even the hardiest among them to helpless nobodies. Day in and day out they braved the adversities of mountain life, carried loads on their backs and mastered the steep, rugged trails, yet the minute they landed in Kathmandu, they needed his help even to cross a busy street” (p.39.)

Only a hardened hill boy like me can and does understand the encyclopedic brevity of the two quotes given above. Shradha Ghale deserves my deepest shradha for her acute observations made so succinctly. For more ennobling inner revelations, readers are asked to read the second half of page 134 and meditate on the rural and urban realities of Nepal.

Yet the Tamule couple, quite oddly, or in spite of it, send their two girls to the posh Rhododendron High School where they have to jostle with “girls from semi-royal and other rich families” of Kathmandu [blurb]. Times may have changed since then in Kathmandu, but the essence of existence is even more acute today. The Bikram tempos and landline phones of their schooldays have become history, yet smartphones and Wi-Fi have brought their own ills and angst in their children’s lives today.

Being an ex-hillbilly of Darjeeling, I personally identify myself with some of the places and persons in The Wayward Girl.

The long and arduous trek Ganga takes from Lungla (Chapter 11) is so personally reminiscent to me. Just change the place-names in the itinerary, and we have a real eastern Himalayan trek with us – For Ganga, it’s along the foothills of the Sagarmatha country, in Nepal; and I in the shadows of the Kanchanjunga Range further east, in Darjeeling.

Another shock of recognition I detected while reading the evocative novel was in the proactive Brahminish Hinduism of the Tamules. My young years in Darjeeling have the same stamp of Nepali tribal men and women going the Jesus Way. Such people dominated and influenced much of the church-planting in Darjeeling, among other places, in the old days. They found the real thuma, the Lamb, in Jesus Christ, and wore their Protestant halo so conspicuously openly that even their convertors, the Scottish Mission’s Presbyterians, were shamed, overshadowed and downplayed in catechism, proselytizing, and episcopal and evangelical callings. In fact, their fourth/fifth-generation descendants have returned to Nepal in various garbs to ready Nepal for the Visitation of Christ the Savior!

But the biggest socket bomb in The Wayward Girl is Boju, the Limbuni grandmother who shoots her one-liners in vulgar volleys and obscene outbursts. Nothing like her has appeared in the Nepali novel to this day. Boju has licensed herself for everything licentious in her domestic domain. That this portrait has been penned by a female writer has all the airs of freedom and deliverance in the Nepali literary firmament. Here is Parijat in direct dialogues. In chaste Sanskritically fundamentalist Kathmandu, Boju’s uncensored lexical items and no-nonsense adages would incite religious and official censure had the novel been written in Nepali. Boju is the unchecked source of laughter and education at the same time. Her classroom is ever lively!

The novel’s Boju is my own maternal grandmother incarnate, the only literate and Protestant Limbuni in our village in Darjeeling who saw Eve as The Carnal Evil Herself in her daily Bible reading! Though not as outspoken as the novel’s Boju, my own Boju was suggestively clear in her multiple misandrous innuendos.

But such verbal shots in the ethnic world is full of informative, educational and entertainment values that are best hurled in the best smutty norms. This is village porn at its best and most conveying way: That the birds and bees of life mustn’t be called by any other names. Spade, after all, is spade at its best; shovel is just another word that has no use when spade is the best available tool at hand.

I say that Boju, Premkala Tamule’s Limbu mother, who lives in her son-in-law’s house and is such a riotously terrorizing woman with the foulest possible mouth, may look like a greatly planned misfit in the novel. Socially it’s an odd arrangement but it’s duly explained in the novel.

In fact, ethnic Nepali society has this openness to make life more comprehendible. That’s why we have such folkways as the all-night Dhan Nach, Rodi, Ratyauli and Juwari or Dohori where every song and dance verges on the erotic and sexually provocative between the sexes. Open society has candid language!

Shradha Ghale is the youngest creative writer among us. Yet she has given us the most incisive novel, and a debut one at that; and as I previously said, novel writing won’t be the same in Nepal and the Nepali world. She has thrown her literary skills and earnest acuities in our court. This is a loud wakeup call for us! We either stand up, or be doomed!

When I finished reading The Wayward Daughter, I remembered the late critic, Mr. Krishna Chandra Singh Pradhan and his plea to us to love the people and the places positioned in a story; they are there not because of their wishes but due to their fateful being where they happen to be in the narration. This is the Way of the Leela, according to the late Mr. Indra Bahadur Rai: This is really about the road taken, and not bemoaning the road not taken. Let us, therefore, relish and rejoice at Shradha Ghale’s study of life that she best knows, as amply demonstrated in her brilliant debut novel. For she has gifted us the kinema (Nepali Kikkoman), philinge (sunflower seeds) and silam (parilla) in her path-breaking novel!

You May Like This

‘Faatsung’ addressing Gorkhaland conflict launches

Indian writer, Chuden Kabimo launched a novel titled ‘Faatsung’ amid a special event organized on Friday in Kathmandu. ... Read More...

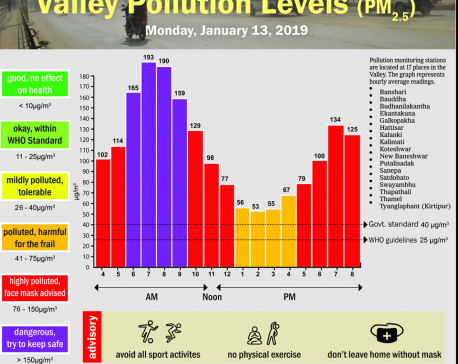

Valley pollution levels for January 13, 2020

Valley pollution levels for January 13, 2020 ... Read More...

Just In

- Qatar Emir in Kathmandu, President and Prime Minister welcome Emir at TIA (In Photos)

- NRM Director Gyawali inaugurates Nagarik Nayak 2081

- Govt amends nine laws through ordinance to attract investors

- NRM to announce two citizen heroes today

- Federal capital Kathmandu adorned before Qatar Emir's State visit to Nepal

- Public transport to operate during Qatari king’s arrival, TIA to be closed for about half an hour

- One arrested from Jhapa in possession of 43.15 grams of brown sugar

- EC to tighten security arrangements for by-elections

_20240423174443.jpg)

Leave A Comment