OR

Medical (mal)practice

Series of ‘medical mistakes’ leave victims in agony

Published On: September 11, 2019 04:36 PM NPT By: Anjali Subedi

Victims recount the details of suffering, file complaint at NMC for malpractice

Kathmandu, Sept 11: Republica’s investigation has found that some of the senior and “well-known doctors” in Kathmandu’s biggest hospitals have shown massive lapse of judgment when handling sensitive medical cases. Sheer negligence of doctors at Grande International Hospital in Dhapasi, Kathmandu has resulted in a series of medical mishaps, leaving patients and their families entrenched in a spiral of financial and emotional issues.

Republica’s investigation reveals a shocking culture of silence, secrecy and massive breach of medical protocols in the handling of sensitive cases.

Case 1: Attempted chemotherapy for a mistaken cancer, family went through intense suffering

When the pregnancy test read positive and another baby was finally coming their way, Meera and Diwakar (name changed) first thanked God for their prayers were finally answered. Two children would make their family complete. They were able to conceive the baby after 11 long years of wait. Nearby their residence is the Grande International Hospital that seemed to attract the affluent class. The well-educated couple from a humble background however wanted ‘the best healthcare’ at any cost. Following up on a suggestion of a doctor in their close circle, they headed for Grande. It was January 2018. Everything went perfect until the baby, a girl, was delivered on August 5 through a C-section.

The new-born had fever; she was kept at the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for four days. A mild injury in her left leg was visible when she was discharged from the unit but the parents were not informed about the injury. The family came home and the baby recovered anyway and there have been no complications so far on her part (though the father later thought it was not fair for the hospital not to inform the parents about the injury, however minor). Meanwhile, the mother’s condition started getting worse; she was having excessive vaginal bleeding. After waiting for two weeks after the delivery, the couple visited the hospital again. Dr Padam Raj Panta, who had handled the case, advised an MRI test.

The MRI report read ‘placental site trophoblastic tumor’ in the patient. The radiologist told Diwakar that a tumor had developed on his wife’s uterus. But when Diwakar wanted to zoom in on the ultrasound image to see the tumor, he was told that the tumor cannot be seen as ‘it was hidden on the back side of the uterus’. Dr Panta was not around to discuss the matter or utter anything about the tumor verbally or in writing (the couple later suspected that it was a deliberate and clever attempt to avoid possible clash or in the worst case, legal troubles).

“It’s a rare condition. Happens to a handful of women in the entire world,” the radiologist said leaving Diwakar shell-shocked. Worried, Diwakar wanted to cross-verify the MRI report. He knew some doctors in Germany from his professional association with an NGO that works in Nepal’s rural health sector.

The next morning, Diwakar was out for work and his wife was in the hospital for follow-up. He got a call from his wife who sounded panicked. “The doctor’s assistant Asmita Ghimire just now told me to be ready for chemotherapy. It is cancer. My life is not long,” she said in a faint voice with painful pauses in between. “You have to take care of our two girls.”

Diwakar rushed to the hospital. When he enquired with Dr Panta if it is too early to start chemotherapy, Dr Panta said it would require further diagnosis.

The family went home with a heavy heart. Meanwhile, doctors from Germany said the mass inside was ‘retained placenta.’ Diwakar quickly googled and found plenty of information on the case. If negligence could be established, they would take the hospital to court as retained placenta could even kill the mother due to excessive blood loss and infection.

While his faith on Dr Panta and the hospital was eroding, he was told that removing Meera’s uterus was the best solution. Diwakar did not argue; he said that he would go for a biopsy test first.

Next day at home, Meera noticed a huge blood clot discharge. Diwakar collected the discharge and ran to the hospital lab for diagnosis. The report wasn’t bad. But the hospital did not stop insisting for the removal of her uterus. When Diwakar reiterated for biopsy test, Dr Panta warned the test could be fatal for the patient.

“But I said, I would take any risk. Actually, the doctor was feeling insecure by then, what was told to us by the radiologist and his assistant was a blatant lie and he, of course, knew that. After getting the report from Germany and reading about retained placenta, I became increasingly suspicious about the hospital,” says Diwakar.

Then a biopsy – extraction of the placenta residue-- was done by the hospital. When the placenta was brought out on a tray, Diwakar asked for a sample. He also asked the doctor whether he can cross-verify the sample, which the doctor could not deny. Diwakar then rushed to the TU Teaching Hospital where someone he knew would split that in three bottles to take them to different labs. “One sample for Grande, one for HAMS and one for Germany,” Diwakar said.

After 10 days, he received a report from Germany that the sample was a 90-day-old placenta and there was no cancer. Diwakar felt cheated by the hospital.

“The doctor wanted to start chemotherapy and anyone in our position would simply go for that. If my sixth sense had not stopped me and if I didn’t consulted the German doctors, Meera would be receiving chemo and the uterus would be taken out as well for sure. I don’t’ think she would be alive today.”

Biopsy reports from Grande and HAMS were also normal; Grande report had no mention of the word ‘placenta’.

After receiving all clear from three tests, Diwakar and Meera visited the Grande doctor, Dr Panta. “He was speechless. The entire team was silent,” Diwakar said.

Talking to Republica on Saturday, Dr Panta said that as a doctor he always tries to save life. But it has also to be accepted that maternal cases are always risky. “I had tried my best in that case too,” he claimed while denying any negligence.

The family paid Grande around Rs 400,000 in hospital bills for the entire treatment and that was after the hospital offered a heavy discount for the fear of retribution. The doctor, who had recommended Diwakar to visit Grande, also told the couple to let go of the incident.

“My wife did not want to discuss the case either. A reputed international medical journal wanted to report the story,” said Diwakar, who had a hard time convincing his wife to give her consent for this story. “What we faced cannot be explained in words, the hospital can never compensate for the psychological stress they had to undergo due to their negligence. Grande is not an international hospital, it’s a money making hospital,” he laments.

Case 2: Five surgeries within 7.5 months, cost Rs 3.5 million, parents give up hope on their newborn

Sanjeev Neupane, 30, was stunned as he was scrolling photos on his mobile at a café in Sundhara last week. His 14-month-old son had a tiny body with an abnormally large head. “This is the latest photo. There is no hope; we are trying to have the best time with him as he can leave us any moment,” the disturbed father said, who has serious complaints against the Grande International Hospital. He has now waged a campaign against the hospital, ‘in order to save many more innocent families from the situation like ours’.

The baby has survived five head surgeries. Those surgeries were performed despite slim possibilities of him getting better. Similarly, he was mistakenly given 66 ml of paracetamol instead of 4 ml prescribed by the doctor. When the nurse was going to administer another dose of 66 ml, the baby’s mother, Ekta, sensed that the dose was unusual and stopped the nurse. She asked the nurse to verify with the doctor. First the nurse was adamant on her judgment but after some time she admitted, “Oh yes, it’s 4 ml only.”

Too many wrong things happened with the boy during his nine months of stay at the hospital, according to the family. From day one till the day when he was discharged with a disappointing note, minor to major mistakes brought a sea of sufferings in the life of the newborn and the parents.

Sanjeev claims that more surgeries would have been performed on his son if he had not intervened or if the paracetamol issue had not emerged.

Sanjeev got a clear picture of the condition of his son only after having the reports studied by other doctors. He took the MRI report also to the Neuro Hospital in Bansbari which finally killed his hope against the ‘repeated assurances’ of Grande doctors that the baby would be okay.

“Grande tries to keep you in the dark as long as it can. They don’t tell you the actual condition of the patient. By the time you learn the truth, you are already broke, and without energy to fight back,” complains Sanjeev, an IT professional from Lainchaur, Kathmandu.

His son was born on June 26, 2018 at Grande. The doctors had assured that everything was alright. “The baby cried well,” which is a sign of a healthy baby, he was told. But after half an hour, the baby started having breathing difficulties. The doctors suspected pneumonia and placed him on a ventilator.

“After holding him for the first time, something magical had happened to me. The moment he was in my arms, I felt he was the most precious thing in my life,” Sanjeev said.

After five days on ventilator, the baby ‘recovered’.

The question that bothers the couple now is why the doctors advised a premature delivery when there was no emergency. The baby was just 36 weeks and one day old and weighed 2.8 kg when he was delivered through a C-section. “Because the doctor insisted, we didn’t question her judgment,” he said.

From the ventilator, the boy was shifted to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where he remained under medication for 16 more days. And during that period, the baby’s diet consisted of expensive, high doses of several medicines. The boy was discharged after 21 days. Parents were told to keep visiting the hospital for follow ups.

But four days later, he developed fever. He was again admitted to the NICU. When tests were done (baby was 26-day old), the reports showed a ‘severe meningitis’. Pus was seen in the fluid extracted from his spinal cord.

“Earlier, when he was discharged after 21 days, they did not tell me that he had meningitis. Now I learnt that when a baby is kept on ventilator for long hours, there is a possibility of him developing infection and it could reach the brain – the possibility of meningitis is high. But in our case, the hospital did not even care to see if the baby had developed infection or meningitis before discharging him,” says Sanjeev. His baby’s case has made Sanjeev study neonatal and pediatric health issues. “If they had acted responsibly from the beginning, things would have been different today.”

Sanjeev thinks only if the doctors had conducted MRI tests early, his son would not have developed meningitis. “It was only on the 26th day that the doctors discussed about the pus in the baby’s head. But they took another 14 days to conduct the MRI,” Sanjeev laments.

Fourteen more days meant that the baby had turned 40-day old. And the MRI report was alarming. Now neurosurgeon Amit Thapa’s team took over the case. Before this, Dr Reema Shrestha, Anju Dangol and Ramita Shrestha had handled the case, according to Sanjeev.

Dr Thapa’s team conducted a series of surgeries to remove the pus from the brain. The baby was 42-day-old when the first surgery was done. Two more surgeries followed. He was 64-day old when the third surgery was done.

Nine days after the third surgery, the baby’s hands moved the pipe and this blocked the release of pus. This meant the pus now needed to be drained internally by inserting a shunt (a medical device) in the head. And this required a fourth surgery.

Sanjeev had never earlier heard about ‘hydrocephalus’. And now it had already taken the baby in its grip. “For the first time, doctors told me about hydrocephalus. But they ruled out such danger. They told me that the baby would be normal after treatment,” Sanjveev said. “If not very intelligent, he will be an average performer,” doctors assured Sanjeev.

When the baby was 74-day old, a shunt was inserted in his head. After a few days, the baby was sent home.

During monthly visits, the neuro team at Grande gave assurances that the baby would gradually recover.

When the baby turned seven months, radiologist alerted that the ultrasound report was not that good. Hydrocephalus had increased. But the neuro team ruled that out and called it ex-vacuo, which according to the doctors was ‘much easier to keep under control’.

By the time the boy turned eight months old, the hydrocephalus was already 8.8 cm by 1.1 cm, according to the Grande radiologist. But the neuro team insisted that it was just 8.8 mm.

“That cannot be cm, that must be mm. The job to interpret the report is mine, not yours,” Dr Amit told Sanjeev.

One month later, the hydrocephalus further grew to 9.8 cm. Dr Amit then admitted that he had earlier mistaken with the reading and advised yet another surgery – a fifth surgery.

After the fifth surgery, the high-dose (66ml) of paracetamol was given to the baby at the PICU. High doses of paracetamol cause damage to the liver. When the nurse was about to give yet another 66 ml dose, the mother had interrupted. “Later, the hospital admitted the blunder,” Sanjeev recalled.

It was after the fifth operation that Dr Chakraraj Pandey started to deal with the baby’s parents. He tried to take Sanjeev and Ekta into confidence. “The cetamol administration was a blunder. But thank god, the hospital saved the baby,” Sanjeev recalls Pandey telling him.

“What’s your age? Oh, you are just like my daughter, this boy is like my grandchild, I will do everything to save him,” Ekta recalls Pandey telling her.

Then the family shared all the pains with him. They also talked about the financial burden, around Rs 3.5 million was already spent for the treatment by then. Dr Pandey told the parents to not worry about the treatment fees.

“But my baby was still suffering from fever and they could not bring down the fever. That was when I grew suspicious about the treatment method,” Sanjeev reported.

At this point, Sanjeev collected all the reports to consult with doctors at other hospitals including the Neuro Hospital in Bansbari. All other doctors told him that there was no need for so many surgeries since the indications were not good from the start.

Since then, the baby is under his parents’ care and they have not gone to the doctor. Sanjeev and his wife Ekta feel bitter about the whole episode. They are exhausted: mentally, physically and financially and they have little hope for the baby’s survival.

Doctors involved in the case, Dr Thapa, Dr Anju Dangol, Neema Shrestha and gynacologist Dr Abha Shakya refused to talk to Republica saying that the case is under scrutiny by the Nepal Medical Council.

Case 3: Lalita loses husband after losing more than ten million rupees

Three more parties came in contact with Republica in the last few weeks to share their painful experiences.

Lalita Dhakal, a resident of Pokhara, is now millions of rupees in debt after her husband’s unsuccessful treatment. The treatment cost her over Rs 10 million. Lalita alleges that she lost him due to Grande’s sheer negligence and greed and insecurities about cost coverage amid ‘Nepal Electricity Authority’s delay in assuring Grande of payment when treatment was halfway through.’

Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) was supposed to cover the treatment cost as her husband was hit by a high-voltage electric shock on August 11, 2017 while walking on the street. NEA had provided her Rs 1.1 million after one month of treatment at Grande and later paid the bills to the hospital.

“During my 80-day stay at Grande, I experienced first-hand their greed for money and how they employ tricks to keep patients longer than required,” Dhakal told Republica. Lalita’s husband Bishnu Bastakoti, who has already passed away, was a well-known physics teacher in Pokhara. He was preparing to leave for the USA to pursue a PhD.

When he was brought to Grande, Bastakoti’s health was improving. Whenever he wanted anything, he would write instructions on paper. “He was sure he would survive,” said Lalita.

But when his condition started deteriorating [he was administered anesthesia for four to five days during treatment and this damaged his kidneys, according to Lalita], she wanted to take him to India or consult the doctors at the burns hospital in Kirtipur.

“But every time I approached them they told me he would be alright. At the start, Dr Chakra Raj Pandey talked so sweet that he gave us the impression that there was no better hospital than Grande. But when NEA started dillydallying on releasing the payment citing high hospital bills, they slowed down the treatment,” Lalita claims. “But at the end, a day before he breathed his last, they told me that I can take him to other hospitals,” laments the mother of a toddler.

NEA’s Managing Director Kul Man Ghising, who is currently in China, told Republica on Sunday that NEA has already paid Rs 7.5 million in treatment bills to Grande. Lalita however says, the expenses were far higher as she had to purchase medicines from pharmacies outside the hospital and the NEA has yet to cover those costs. “We were allowed to leave the hospital only after the NEA signed an agreement promising to clear the remaining bill.”

While Ghising says no one should be blamed for the death as the patient was in serious condition, Lalita claims that if the patient was serious he would have died instantly.

After her husband’s death, Lalita looked for lawyers to fight her court case but no one was ready to take her case. She was told that she can never win a court case against the hospital.

“My brother, who’s also a doctor, encouraged me to file a case as he understood many flaws in treatment, but we didn’t find a lawyer,” she said.

“Dr Arjun Karki, who was involved in my husband’s treatment, told me that he does not remember the case as he handles thousands of cases and instead asked me to contact Dr Subhash Acharya.”

Dr Subhash Achrya, the assistant chief at Grande ICU, dismisses Lalita’s allegations as baseless. “We had not stopped them from taking him elsewhere for treatment. Although there was improvement in the beginning, his health later deteriorated. It is very likely that a person with severe burns, kept in ICU, contracts infection,” he said, adding that Lilita is free to go to the court if she wishes.

Meanwhile, Sanjeev, the father of the baby with hydrocephaly, has filed a complaint against Grande at Nepal Medical Council (NMC).

According to Dundhiraj Paudel, the chief of the ethical committee at NMC, they are investigating the case. “After serious investigations (recording of statements of the doctors and the victim party included), our experts have found that there were problems since the baby’s birth and the neuro doctors alone were not responsible. Based on the reports given by experts, the council will prepare a final document and soon hand it over to the parties concerned,” he told Republica on Friday.

Meanwhile, Dr Pandey defended that a hospital never makes mistakes knowingly. “Health Ministry and NMC are looking into the matters,” he said.

You May Like This

Patient from Jhapa tests negative for COVID-19

KATHMANDU, March 16: A patient who was brought to Kathmandu from Jhapa on suspicion of COVID-19 infection has tested negative,... Read More...

Jhapa reports one suspected case of coronavirus

BHADRAPUR, March 15: Jhapa has one suspected case of coronavirus, and the suspect has been sent to Kathamandu for further... Read More...

Just In

- Nepalis living illegally in Kuwait can return home by June 17 without facing penalties

- 'Trishuli Villa' operationalized with Rs 100 million investment

- Unified Socialist rejoins Lumbini Province govt following ministry allocation

- Police release ANFA Vice President Lama after SC order

- 16 hydroelectric projects being developed in Tamor River

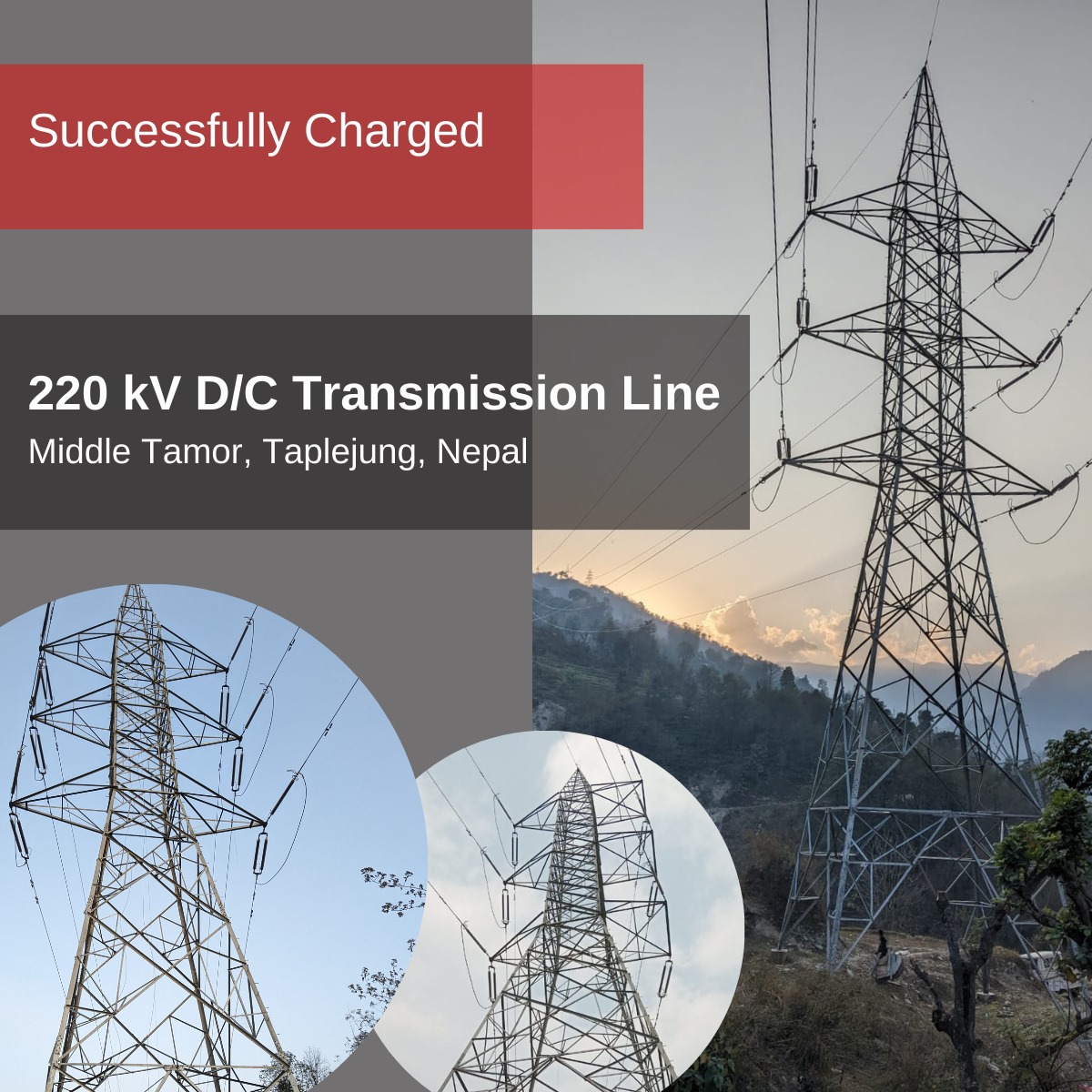

- Cosmic Electrical completes 220 kV transmission line project

- Morang DAO imposes ban on rallies, gatherings and demonstrations

- Gold smuggling case: INTERPOL issues diffusion notice against accused fugitive Jiban Chalaune

Leave A Comment