OR

When intelligentsia, political class and public intellectuals fail to take clear stands, the whole debate flies into abstractions

After seven months-long intense agitation in 2015/16 and protracted standoff with Kathmandu, Madhes mudda (Madhesh issue) seems to be finding a resolution in increase of a few local units in Tarai plains (if materialized) and Madhesi forces’ participation in local polls. Because second phase polls are unstoppable despite all odds and constitution amendment is next to impossible so long as current parliamentary equation stands intact, Madhesi parties have no option but to join election fray and test their ideas at ballot boxes. Some may interpret this development as yet another ploy of hill elites to foist ‘internal colonization’ upon Madhes.

But my focus in this article is on why political parties, Nepali intelligentsia, civil society and media failed to build consensus opinion on ‘core’ Madhes issues.

Everyone says genuine grievances of Madhesis must be heeded, and Madhesi forces brought into confidence. All sections of the society need to be taken on board in course of constitution implementation. Nobody should look down on Madhesis because they are Nepalis, goes the argument. No denying that.

The argument makes sense. That we need to respect individual and community identity of all and that every one should be accorded human dignity is beyond dispute in a civilized society. But in Nepal we have used such arguments to escape specificities. This is precisely what has hindered meaningful resolution of Madhes issue. Neither the political parties, including Madhesi forces themselves, nor the intelligentsia that purportedly champion Madhesi cause, has been able to get specific about Madhesi agenda. They have all indulged in abstractions.

One demand of Madhesis has been that they should have proportional inclusive representation in state bodies. So where does the constitution prevent Madhesis from sharing equal state power?

I tried to elicit a response to some contested questions during a meeting with a group of Madhesi journalists last week. First, they pointed to government decision on appointment of ambassadors and high court judges.

“How many of ambassadors are Madhesis?” one asked. “How many of high court judges are Madhesis?” other rejoined. “Tell me, how many Madhesis have been represented in the cabinet?”

But is this not because top leaders at the helm have always favored their loyalists in powerful positions? I asked. When leaders like Pushpa Kamal Dahal, Sher Bahadur Deuba and KP Oli disregard the spirit of inclusion, we need to hold them to account, not blame the constitution, I argued. “But we have rarely been treated on equal footing,” came the reply.

“When earthquakes devastated the hills in 2015, we in the plains got organized and reached as far as Gorkha and Sindhupalchowk with sacks of rice and other relief materials to help the victims. We supported you when you were in trouble. But when we in Madhes were observing September 20 as black day, you were celebrating in Kathmandu. When the police killed Madhesis, you did not even come to sympathize with us,” they said almost in chorus.

But I am talking about the constitution, I reminded.

Madhesi forces say language provision is discriminatory. UML argues proposed amendment on language is a ploy to make Hindi language of official business. Then Madhesi friends started to speak about history and glory of Maithili. Maithili is perhaps the oldest language of Nepal, one of them said.

I understand half of spoken Maithili and love this language myself. So I listened to him eagerly. But the constitution does not hinder promotion of Maithili, I told him. “But when and where has it happened?” he asked.

Then I entered citizenship debate. I began by saying the constitution does not allow dual citizenship. “Who says we want dual citizenship?” they said. They told me that their relation with people across the border should not be constrained by idea of citizenship.

They argued that cross-border marriage has been taking place between Nepal and India for centuries and therefore women married to Madhesis should not be seen as “foreigners.” They reminded me of how top leaders of so-called ‘nationalist’ parties have married Indian women and yet why nobody questions their nationality.

But if we regard an Indian woman married to Nepali as a special case and lift constitutional restrictions on her, should it also not be the same in case of Nepali men who marry, say, Chinese, American or German women? If we grant citizenship by descent to Indian women married to Nepali men, should this rule also not apply to others who marry someone from outside the country?

Madhesi friends responded to this with a short pause and then broached province demarcation dispute.

When a group of hill men protest against boundary provision, the government becomes ready to readjust the boundaries. But when we do the same for over six months, we are not heeded. I told them that province demarcation has become complicated because of adamant stand of Madhesi forces against incorporating hills and plains within any province. You sound like a UML spokesperson, they dismissed me teasingly.

Then these friends turned to unfair treatment argument.

Kathmandu persecuted us based on the color of our skin. Madhesis were subjected to historical marginalization. You call us dhotis, they said. It is true that Madhesis were subjected to humiliation by Kathmandu rulers in the past. But to resort to this argument to justify it as Madhes mudda would be tantamount to falling into, what American literary critics William Kurtz Wimsatt and Monroe C Beardsley call, affective fallacy (judgment you make based on emotional effects of what someone has to say) and intentional fallacy (the conclusion you draw by saying that so and so person is against you because he has bad intention towards you).

But we fall into this trap sometimes. Eminent Nepali journalist Ameet Dhakal wrote an appealing article in March, explaining how Pahades have knowingly or unknowingly hurt Madhesi sentiment by treating them as outsiders. He argued that we Pahades should not hesitate to publicly apologize for the mistakes of the past. Some Madhesi intellectuals had liked and appreciated Dhakal’s argument in social media.

If this is what Madhesh issue has come down to, we should be ready to apologize a hundred times. If asking for an apology for mistakes of past rulers can strengthen harmony between Madhesis and Pahdes, let us a run a national campaign for it.

But we are talking about constitution here.

When intelligentsia, political class and public intellectuals fail to say what is right and wrong, what is just and unjust, what should be done and what should not, the whole debate flies away into abstractions. This is what has happened in Nepal for the past two years.

Therefore we need to come clean on the following questions: Should Hindi language be given official status in Nepal? If it should, how will it contribute to preservation and promotion of indigenous languages? Should Indian nationals married to Nepalis be considered as a special case and should laxity of citizenship be maintained only for such citizens? Should we have one rule for Indian women married to Nepali men and another for women of other countries married to Nepalis? Must we ignore resource complementarities between hills and plains while revising federal boundaries? Should not people of the concerned provinces be allowed to have their say on boundary alteration?

Lack of clarity on these key questions has bogged down progress in constitution implementation. Many of us avoid these questions. Instead we resort to abstraction and emotionality: Madheshis are also Nepalis. Let us be kind to them. Such tactics work only for a short time.

I take recent Indian “shift” on Nepal in the same light. A day before ‘great Indian shift’ was reported in Indian press, I was in Delhi with those thought to be among the architects of India’s Nepal policy. I sought their views on some of the ‘contested’ constitutional issues.

I don’t see any problem with language and citizenship issues, they are making controversy out of it for controversy sake, one of the prominent former Indian bureaucrats said. On province demarcation, he said, it is up to Nepali people to decide. Delhi also seems to have realized it went too far with Nepal in 2015/16.

With the conduction of first phase local polls, we have formally started process of constitution implementation. As is the case, political parties have started to use emotional appeals to impress their constituencies. Those who misled the people through victim narrative will again resort to sentimental politics for as long as it will work. Members of intelligentsia and even civil society wallowed into sentimental abstractions for far too long. It’s time for them to get rational and pragmatic. Unless we can separate emotionality from constitutionally contested ideas, constitution amendment debate will drag on indefinitely.

mahabirpaudyal@gmail.com

You May Like This

Whither civic sense?

The better educated our citizens are, the better equipped they will be to foster good governance. ... Read More...

Sense of style

When it comes to fashion tips, it sometimes seems that everyone has tried-and-tested style advice they absolutely swear by. Some... Read More...

Knocking sense into CSR

There is lack of understanding on benefits of CSR in Nepal as companies fail to understand how it benefits them in... Read More...

Just In

- Govt padlocks Nepal Scouts’ property illegally occupied by NC lawmaker Deepak Khadka

- FWEAN meets with President Paudel to solicit support for women entrepreneurship

- Koshi provincial assembly passes resolution motion calling for special session by majority votes

- Court extends detention of Dipesh Pun after his failure to submit bail amount

- G Motors unveils Skywell Premium Luxury EV SUV with 620 km range

- Speaker Ghimire administers oath of office and Secrecy to JSP lawmaker Khan

- In Pictures: Families of Nepalis in Russian Army begin hunger strike

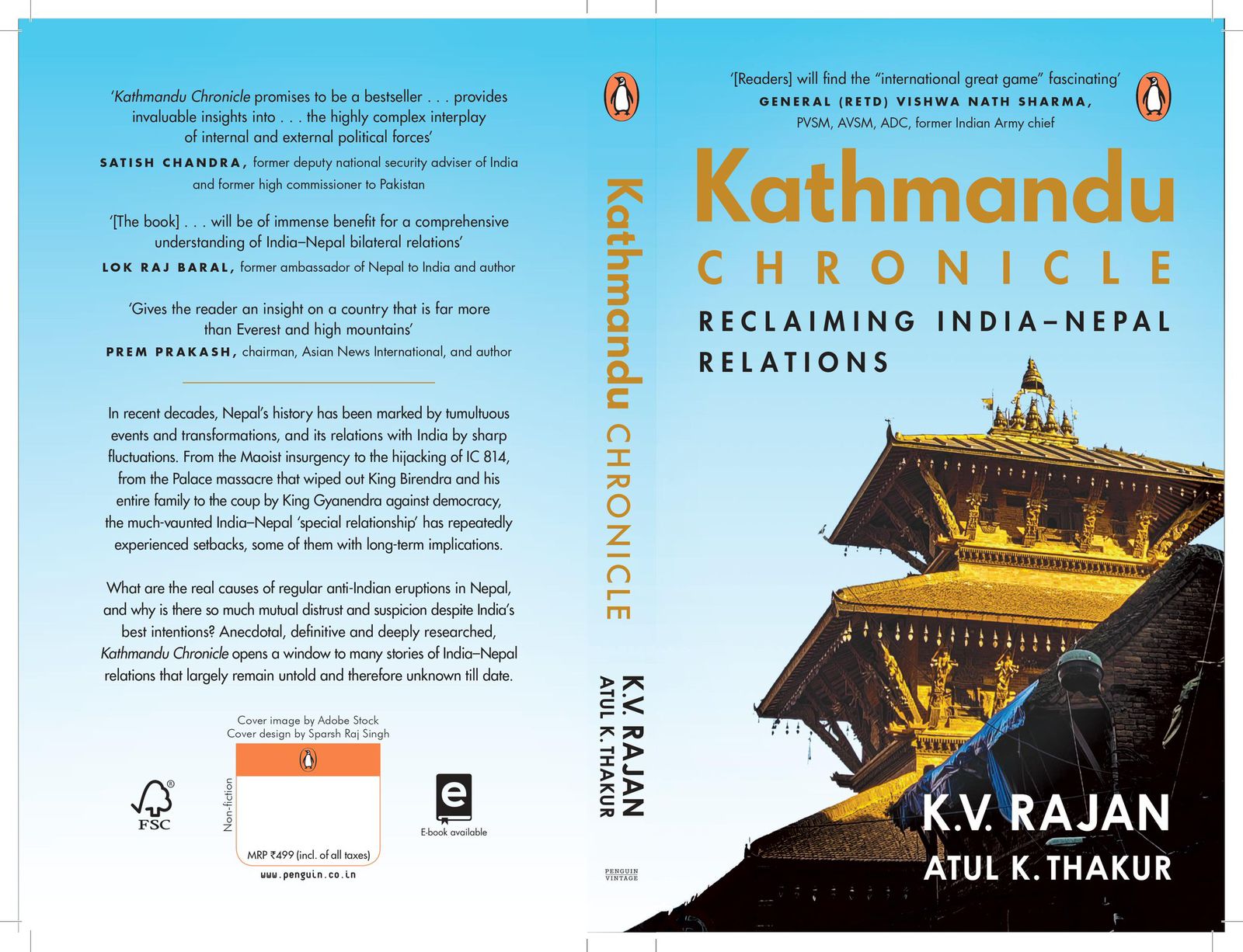

- New book by Ambassador K V Rajan and Atul K Thakur explores complexities of India-Nepal relations

_20240419161455.jpg)

Leave A Comment